Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Night of the Wolves»

Praise for the novels of

HEATHER GRAHAM

writing as Shannon Drake

“Drake constructs a well-drawn plot and provides plenty of sexual tension and romantic encounters as well as exotic scenery.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Pirate Bride

“Bestselling author Drake … keeps Ally’s relationship with her aunts and godparents playful, forming an intriguing contrast with the grim progress of the murder probe, while satisfying romantic progress and rising suspense keep the book running on all cylinders.”

—Publishers Weekly on Beguiled

“Drake is an expert storyteller who keeps the reader enthralled with a fast-paced story peopled with wonderful characters.”

—RT Book Reviews on Reckless

“[Shannon Drake] captures readers’ hearts with her own special brand of magic.”

—Affaire de Coeur on No Other Woman

“Bringing back the terrific heroes and heroines from her previous titles, Drake gives The Awakening an extraspecial touch. Her expert craftsmanship and true mastery of the eerie shine through!” —RT Book Reviews

“Well-researched and thoroughly entertaining”

—Publishers Weekly on Knight Triumphant

Also available from

HEATHER GRAHAM

writing as

SHANNON DRAKE

THE PIRATE BRIDE

THE QUEEN’S LADY

BEGUILED

RECKLESS

WICKED

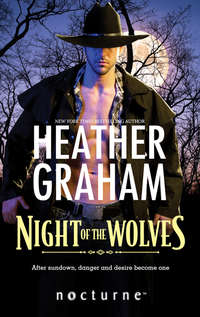

Night of the Wolves

Heather Graham

To some of my favorite Aussies,

with a bit of Kiwi, too.

Rosemary Potter

Cherie Watts

Christina Tanvadji

Frances Bomford

Monthiti Danjaroensuk

Margaret Bell

and

Mandi Hutton

PROLOGUE

1838

The Republic of Texas

FIRST SHE HEARD THE HOWLING of the wolves. In the West, once you got past the cities and out on the trails leading to the lands of the ranchers and homesteaders, the sound wasn’t unusual. It was still eerie, but it wasn’t unusual.

But this was so early.

And after that, when the air went so very still …

That was when Molly Fox knew that something was wrong, seriously wrong.

Bartholomew, who was generally a fine guard dog, was acting like anything but. He started to whine, tucked his tail between his legs and, keeping low to the ground, crept into the bedroom and under the bed.

The strange silence continued. Molly listened, but she couldn’t even hear the sound of the wind moving through the trees.

Taking Lawrence’s old rifle, she went out on the porch. As she stood there, she saw the dying sun far on the western horizon.

As she watched, it seemed to fall to the earth like a fiery globe, sending out tentacles of flame to tease the heavens. It was beautiful, but then, as if it had been enfolded in a dark blanket, it suddenly disappeared as it plummeted to the earth. The last vestiges of pink and pale yellow, mauve and silver, faded from the sky. Even twilight was gone; night had taken over.

Molly stood in the darkness for a moment, then gave herself a shake and quickly retreated inside to light the kerosene lamp on the table.

Bartholomew was still cowering in the bedroom.

“Come out, you ragamuffin,” Molly called, though she was still illogically unnerved herself.

She was accustomed to living out here. Lawrence and she had picked up stakes from Louisiana and come here to accept her inheritance from a father she’d never met: a small cattle ranch, but not a very profitable one. Still, they had been able to hire five hands, who lived in the bunk-house just the other side of the stables, and she even had a girl in from town to help her clean the place and keep up with the cooking, five days a week. They were young; they spent their nights dreaming and their days working hard to make those dreams a reality.

When he was off on a cattle drive, like the one he had recently left on, Lawrence didn’t like to leave her alone, and he’d once suggested that they splurge for her to stay in town, but she hadn’t wanted to go. He worried about a rogue cowhand or a rustler, or a plain old villain of any variety, who might come along. But she knew how to shoot, and she would hear a horseman coming. Plus she had Bartholomew—who at the very least made a terrible ruckus if there was a stranger around.

He didn’t usually hide under the bed.

Molly set about lighting the rest of the lamps in the parlor and dining area, kitchen, and even her bedroom—she didn’t want Bartholomew spooked any further. Just moving around and doing something made her feel better.

Then the wolves started howling again, and Molly heard Bartholomew whining softly in fear.

“Bartholomew, you are not a hound, you are a chicken,” Molly called to the dog, trying to find a semblance of inner calm. “Those are just wolves, silly dog. Your cousins, in the grand scheme of things.”

Her own voice sounded unnatural to her.

And even as the sound of her words died, she was listening again. And what she heard—or rather, didn’t hear—was disturbing.

The silence was back. A heavy silence that somehow just shouldn’t be.

She’d left the gun by the door, and she quickly went back for it. Clutching the rifle with one hand, she carefully opened the front door again and walked back out on the porch.

There was nothing out there. The moon was rising high now—maybe the wolves had known it was on the rise, climbing up in the sky even as the sun had died in all its magnificent splendor. She could see the yard in front of the house, the strong fence Lawrence and the men had built, and the paddocks beyond. She had gone out earlier and fed the two horses that remained in the stables, along with the chickens, and she was glad—she didn’t want to be far from the house now, or even Bartholomew, for whatever he was worth. She saw nothing, heard nothing, and yet she was afraid. She wished that she would hear the sound of hoofbeats or rowdy cowhands—or even outlaws; she could handle ill-mannered men, despite Lawrence’s fears for her. She blushed. Lawrence was convinced that she was beautiful, and that, surely, everyone saw it. She prided herself more on an admirable sense of honor; she believed in God and believed that He wanted most for everyone to be decent to one another. Whenever she said so, though, Lawrence would shake his head, smiling, rolling his eyes, and tell her that she was naive. But she was still happy. He loved her. And he was such a gorgeous man himself. Tall and strong, and so capable; she even loved his callused hands, because he got those calluses working for her. For their dreams. But he did worry.

She had the respect and friendship of most folks in town; she certainly wasn’t afraid of them. Not even of any of the local cowhands or farmers; she could quell their bad behavior with one disapproving look.

No, she was never afraid….

Molly went from window to window, making sure they were all securely latched. The house had been built with a breezeway, Southern-style, so she went to the back door and assured herself that it was locked and latched, as well.

All the lamps were on.

The world was still eerily silent.

She set water on the stove to make herself a cup of tea. She had best get over this silliness, she told herself. It would be weeks before Lawrence returned from his cattle drive.

While the water heated, she marched herself into her bedroom.

Bartholomew had come out from beneath the bed, but he was still crouched low, and he was making a strange whining sound.

“Barty, stop it!” Molly implored. She went to her dressing table. The kerosene lamp set strange shadows to dancing around the room, something that didn’t help her jitters. Her face appeared gaunt in the mirror, her hazel eyes reflecting back at her filled with a shimmering gold. Her hair caught the light and seemed to spark with fire, appearing more red than usual. She picked up her brush and began to count out a hundred strokes.

Bartholomew barked. She turned to look at him. “Barty!”

He whined, and thumped his tail on the floor.

Letting out a sigh, she turned back to the mirror.

And that was when she saw him.

She let out a startled scream, then turned with a gasp and relieved laughter.

It was Lawrence. Somewhere he had changed from his cattle-drive denims and cotton shirt; he was dashing in a black suit and crimson vest, and a high black silk hat. He was so straight and strong, such a handsome man. Cajun blood ran through him; his brows and neatly maintained mustache and beard were pitch-black, like his hair and eyes. His features were strong and his mouth was generous, his smile filled with a sense of fun and just a shade of wickedness.

She started toward him, then froze.

There was something wrong. His face was so pale. He lifted a hand, as if to keep her away.

“Molly,” he whispered. “Molly, I love you.”

He was sick or injured, she thought; he looked as if he were about to fall. Filled with her love for him, she went to him.

“What happened? My God, Lawrence, how did you even get in here? I had the place all locked up. Never mind. What’s wrong? Where are you hurt?”

She slipped her arms around him, leading him to the foot of the bed. They sank down together, and he turned and stared at her. He had to be fevered, and yet he was cold to the touch. She brought her fingers to his face, tears springing to her eyes. “My love, what’s wrong?”

Shaking, he lifted his own hand to her face, his gaze intense as he told her, “Molly, I love you. I love you so much. You are everything that I’ve lived for, everything that’s good and wonderful and pure in life.”

Then he kissed her, and though his lips were chilly at first, there was passion in his touch, and he seemed vibrant and vital and…

Desperate…

He kissed her deeply, with a hunger that was seductive all in itself. The way that his tongue moved in her mouth was suggestive and wildly sexual. She felt his fingertips on her shoulder, tugging at the cotton of her blouse, and the fabric that ripped and tore as he removed it seemed of little consequence. He threw off his hat, lifting her higher on the bed, and the fever was in his eyes as he looked down at her, then buried his face against her throat, her breast. “I love you. I love you so much. I shouldn’t be here, but I have to be here. By God, I won’t do another man ill, but I must be here.”

She threaded her fingers through his rich dark hair. “I love you—I’ll always love you—and you belong here.”

He said something, but it was muffled against her flesh as he kissed her breasts, laved them with his tongue, teased them with his teeth, a small pain, but one that was oddly erotic. Their clothing wound up strewn everywhere, and she had never felt more feverishly, thoroughly kissed. He seemed to cover every inch of her body even as she struggled to return the liquid caresses, his urgency streaking through her with the fury of a lightning bolt. Somewhere in the back of her mind she still worried that he was ill. But he couldn’t be that ill; no man could love with such steely passion if he were ill….

He paid careful attention to all of her, first the entire length of her back, and then he flipped her over and caressed a slow and lazy zigzag pattern over her collarbone and breasts, down to her navel, her hips, her inner thighs, and then between them. She shrieked and clawed at him, and eventually brought him back to her. She couldn’t have felt more loved and sensual and sexual than when he rose above her and thrust into her. He loved her with his body and with his very soul, and she was dazzled and flying, whispering, crying out, soaring higher and higher. When she climaxed, the world seemed to burst like Chinese firecrackers and then tremble as if they’d been caught in an earthquake. Afterward, she clung to him, drifting back to sanity amid the shadows of their bedroom.

She lay still, catching her breath for the longest time, and then she curved into him and said, “Lawrence, why are you back? You’re not due for—”

He brought his fingers to her lips. “In time,” he whispered. It almost sounded as if he were crying, but she didn’t question him. She knew him well enough to know he would answer in his own time. They had grown up together, had spun their dreams for a life with each other forever.

He held her close for a long time, and then they made love again. Throughout, he whispered “I love you” so many times that she lost count.

And when she slept, it was in the comfort of his arms, basking in the love of their youth and their dreams for the future.

But in the morning he was gone.

She was amazed, disbelieving. She even went into town and asked if anyone had seen him. Sheriff Perkin looked at her as if she were plumb crazy.

“Why, Molly, my dear, you know he’s off on the trail with his hands. Honey, the man’s barely left. He wouldn’t be human if he’d made it back here so fast, now would he? Are you sure you’re all right out there? You’re looking kind of peaked. You ought to come in and stay with my Susie. With our boys off helping on the cattle drive, she’s right lonely.”

Molly thanked him but said that she couldn’t stay. She went home, completely perplexed. Lawrence had been there on what she’d come to call the night of the wolves, for that eerie howling. She knew it. She could still see his eyes, still hear his words, feel his touch. He loved her; he had made love to her.

It was two days later when Doc Smith came out with the sheriff and his sweet wife, Susie. All three were pale and drawn.

She knew something was wrong. She had actually known it from the moment she heard the horses’ hoofbeats. She stood on the porch, clutching the rail as they approached. By her side, Bartholomew let out a low and mournful howl.

Just like the wolves.

She was afraid. More afraid than she’d ever been in her life. And when the sheriff walked toward her, his old bulldog face filled with grief, she knew.

“No!” she said. “No, he’s not dead. Lawrence isn’t dead. He isn’t, he isn’t, he—”

“My poor dear!” Susie Perkin, pretty and round, hurried to Molly, taking her into her arms.

“They were attacked right outside town, just a few days after they left. Cattle rustlers, I’m thinking, ‘cause there wasn’t sight nor sound of any cattle to be found,” Sheriff Perkin said. “Cattle rustlers … Comanche or Apache, most like. We can’t rightly tell which. But there are some arrows at the site … some feathers, but—”

“No! Lawrence knew the local tribes and the shamans and the war chiefs. He didn’t die at the hands of any Indians, I know that!”

Doc Smith was as kind a man as you could ever want to meet, and he took Molly’s hand now. “You’ll come back into town with us,” he said.

“And Bartholomew, too,” Sheriff Perkin said.

“But he’s not dead. He was here! And he’ll be back. Anytime now, he’ll be back!” Molly told them. She was falling, but they were there to support her. “He was here, and that’s why I asked you if you’d seen him. He was home, but then he up and disappeared. He’s not dead, though,” Molly told them. “And I won’t believe he is. Not unless I see his body, I won’t.”

“Oh, Lord, she can’t be seein’ that body,” Doc Smith whispered.

“It’s not him. I know it’s not. I don’t care what you say, it’s not him,” Molly protested.

“There, there,” Susie told her helplessly.

In the end, they had to show her what was left of the body.

It was in Lawrence’s clothing. It held Lawrence’s pocket watch and his billfold. There was a gold chain around its neck with a big locket that carried a picture of her. The matted, bloody hair that remained was black. The body had been found with five others, and those men, she was certain, were their hands. Jody, who laughed all the time. Beau, who was big as an ox. Daryl, Steven and Jacob, too.

After insisting that she be allowed to see them all at the funeral parlor in town, Molly was horrified. At last it was more than her consciousness could bear. She passed out.

As she fell, she admitted that yes, the first man was Lawrence.

Immediately she told herself that no, it wasn’t Lawrence. Lawrence had come to her, had made love to her, after this … thing was dead.

It was about six weeks later when Molly knew for certain, at least in her own soul, that she had been right. She didn’t know how; it was a mystery she would never fathom. But Lawrence had come to her that night.

She was expecting.

She rented her house and land to a neighboring rancher, and thanked the Perkins for all they had done for her, then told them that she couldn’t stay, that she had to go home to what family she had, back to Louisiana, to the city. They wept when they saw her off in the stagecoach. She wept, too. They had been good friends. She knew they wanted her to stay, to fall in love again.

But she loved Lawrence. He loved her. And she would spend the rest of her life waiting.

He had come once; he might come again.

And meanwhile, she would have her child to raise.

CHAPTER ONE

Summer

1864

DARKNESS HAD COME to New Orleans. Though the detested Union military governor Benjamin “Beast” Butler had been removed from control over the city, the streets remained quiet by night, as if the residents’ hatred of the man were an odor, and that odor still lingered in the air. As he approached the office on Dauphine where he’d been summoned, Cody Fox was surprised by the sudden eruption of men, exiting headquarters and hurrying out to the street, rifles in their hands, faces pale, nervous whispers rather than shouts escaping their lips.

He was curious about what was bothering the men. New Orleans was solidly in Union hands and had been for more than a year. As the others hurried out, barely nodding in his direction, Cody went in, wondering what a Union officer wanted from a recovering Confederate soldier. The sergeant behind the desk took his name and bade him sit, then hurried into what had once been the parlor of Missy Eldin, daughter of Confederate Colonel Elijah Eldin, who had died at Shiloh, but was now a Union military office.

Cody had returned from the front lines nearly a month ago, and as far as he was concerned, he had healed from the wound that had taken him out of the battle and sent him back to the house on Bourbon Street where he had grown up. He was walking fine these days, he had no problem whatsoever leaping up on his horse, and all he had in mind now was getting somewhere far away.

He wasn’t afraid of battle; he wasn’t even afraid of the enemy, especially since he and his Southern fellows lived side by side with “the enemy” these days. Cody had discovered long before the war that there were good and bad men of every calling, and there were good men and bad on both sides of the present conflict. No, he was simply tired of the carnage, restless, ready to move on.

But he’d been called to the headquarters of Lieutenant William Aldridge, adjunct to Nathaniel Banks, the commander who had replaced “Beast” Butler. Butler had ordered the execution of a man named William Mumford, merely for tearing down the Stars and Stripes when it had been raised over city hall. The act had made him a savage not only in the eyes of the South, but even in the North and among the Europeans. Nathaniel Banks was a decent man, and he was working hard to undo the terrible damage caused by Butler, but it would take time.

“Mr. Fox?” A soldier in a federal uniform, an assistant to an assistant, called him, refusing to acknowledge his rank. He really didn’t give a damn. He hadn’t wanted to go to war; it had seemed that grown men should have been able to solve their differences without bloodshed. Then again, he had no desire to be a politician, either.

These days … everyone was just waiting. The war would end. Either the Northerners would get sick to death of the toll victory would cost and say good riddance to the South, or the continual onslaught of men and arms—something that could be replenished in the North and not the South—would force the South to her knees. He’d once had occasion to meet Lincoln, and he admired the man. In the end, Lincoln’s iron will and determination might be the deciding factor. Lee was definitely one of the finest generals ever to lead a war effort, but no man could fight the odds forever.

“Yes, I’m Fox,” Cody said, rising.

“Come in, please. Lieutenant Aldridge is ready to see you in his office,” the assistant to the assistant said.

Cody nodded and followed the man.

Lieutenant Aldridge was behind a camp desk neatly installed in the once elegant study. He had clearly been busy with the papers scattered in front of him, but when Cody entered, he stood politely. Aldridge was known as a decent fellow, one of those men who were convinced the North would win and that, when that day came, the nation was going to have to heal itself. It might take decades, because it was going to be damned hard for folks to forgive after Matthew Brady and others following in his footsteps had brought the reality of war home. Brady’s photographs of the dead on the field had done more to show mothers what had happened to their sons than any words ever could have. But Aldridge was convinced that healing would come one day, and he intended to work toward that reality.

“Mr. Fox,” Aldridge said, shaking Cody’s hand and indicating the chair in front of his desk. “Thank you for coming in. Would you like some coffee?” He was tall and lean, probably little more than thirty, but with the ravages of responsibility adding ten years to his features. His eyes were hazel. Kind eyes, though.

“I’m fine, thank you,” Cody said. He leaned forward. “May I ask why I’m here?”

Aldridge pulled a file from atop a stack on his desk and flipped it open. “You were with Ryan’s Horse Guard, I see. Cavalry. You saw action from the first Battle of Manassas to Antietam Creek, and you nearly had your leg blown off. Doctors said you wouldn’t make it, but somehow you survived. You’ve been back here in New Orleans for a year—got your medical degree up at Harvard, though.”

Aldridge paused for a moment, staring at him. “Any corrections thus far?”

“No, sir. None that I can think of,” Cody said, still wondering why he was there.

Aldridge dropped the file. “Anything you want to add?”

“Seems like you know a lot about my life, sir.”

“Why don’t you fill me in on what I’m missing?” Aldridge asked, a fine thread of steel underlying his words.

“What exactly are you asking, Lieutenant?” Cody asked.

“I was hoping you’d be more … forthcoming with the details of your time in the North, Fox,” Aldridge said. “Before your state seceded, you were working in Washington. You were actually asked to the White House to converse with Lincoln. You’ve been involved in solving several … difficulties in and around the capital.”

Cody kept his face impassive, but Aldridge’s knowledge of his past had taken him by surprise.

“I took part in a number of reconnaissance missions as part of Lee’s army, Lieutenant, if that’s what you’re referring to,” he said carefully. “I was given a medical discharge and sent back to New Orleans when I was wounded—initially declared dead, actually. I’ve been here, helping the wounded of both armies and minding my own business, since my recovery.”

Aldridge stared at him and flipped the file shut again. He didn’t have to read from it; he apparently knew what it contained. “A series of bizarre murders took place in northern Alexandria in 1859. You were friends with a certain law enforcement officer, Dean Brentford, and you started patrolling with him at night. You apprehended the murderer when no other constable could catch up with him. And when he tore through the force trying to subdue him, you managed to decapitate him with a single one-handed swing of your sword.” Aldridge pointed a finger at him. “President Lincoln himself asked you to perform intelligence work for him, but you politely refused, saying your remaining kin were in Louisiana, and you couldn’t rightly accept such a position.”

Cody lifted his hands. “My mother died the year after the war started, but I’m sure you understand that … I come from here. I was born here. And as to the … incident to which you refer … The brutality of the murders took everyone by surprise, and I’m simply glad I was able to help.”

Aldridge leaned forward. “Help? Fox, to all intents and purposes you and you alone stopped them. More to the point, we’ve just had a similar case here, down on Conti. My officers are at their wits’ end, and I don’t want this city going mad because the Yanks think the Rebs have gone sick or vice versa. This isn’t a battleground anymore, it’s a city where people are picking up the pieces of their lives. It may take decades before true peace is achieved, but I’ll be damned if I’ll allow the citizens to start killing one another because one man is sick in the head.”

Cody stared straight across the desk at the man and didn’t say a word.

“You got yourself a medical degree, son, then you went off to ride with the cavalry and wound up in intelligence.” Aldridge stared back at Cody, hazel eyes intent. “You can help me. I don’t give a damn where you came from or what your folks did or whose side you fought on. I just want to catch a killer. Because it sounds like a bloodthirsty madman just like the one you killed is on the loose—in my city—and I want him stopped.”

“HOW DID YOU KNOW about the attack?”

Alexandra Gordon was sitting in a hardwood chair, presumably before a desk, but she didn’t have any actual idea where she was, since the officers who had come to her house had thrown a canvas bag over her head, and she was still blinded by it. She was stunned by the treatment she had received and continued to receive, especially since she had put herself in great peril to warn the small scouting contingent that there would be bloodshed if they crossed the Potomac.

Apparently she was a deadly spy.

They had tied her hands behind her back, but the officer in charge had whispered furiously to the others, and her hands were once again free. Despite that small courtesy, he seemed to be the descendent of a member of the Spanish Inquisition. He slammed his hands on the table, and his voice rose as he repeated the question. “How did you know? And don’t say again that it was a dream. You are a spy, and you will tell me where you’re gaining your information!”

She shook her head beneath the canvas bag, praying for the ability to stay calm. “I merely tried to save Union lives, sir, as well as Confederate. What, I ask you, was gained by this raid? Nothing. What was lost? The lives of at least twenty young men. I went to the encampment to speak with the sergeant and tell him that he mustn’t make the foray. He ignored my warning, and now he and his men are dead, along with a number of my Southern brothers.”

“I have the power to imprison you for the rest of your life—or hang you,” her inquisitor warned.

She heard the sound of a door opening. Someone else spoke, a man with a low, well-modulated voice. “Lieutenant Green,” he said, “I would like to speak with Ms. Gordon myself.”

“But, sir!” Green was shocked.

“Please,” the new voice said politely, but there was authority in the tone.

Alex heard a chair scrape back and was aware of the newcomer taking a seat across from her.

“My wife has dreams,” he said after a moment. “In fact, I have had dreams. Please, tell me, what did you see in your dream, and how did you know when and where the slaughter would occur?”

“I know the place,” she said softly. “I used to play in that hollow when I was a child, when we had a farm there. My father worked in Washington then, but we would steal away to the countryside whenever he was free.”

She heard someone snort. Green. “Her father was a traitor,” the lieutenant said. “He went out West and was murdered. Indians, I heard. Good riddance.”

She stiffened at that. “My father was no traitor. He loved the West and chose to move us there to avoid a war he thought unjust. He went looking for a home where everyone was equal. He didn’t care about a man’s birth or color. He was a brilliant man,” she said passionately. “He worked for the government, for the people.”

“It’s all right, I know of him, Miss Gordon,” the newcomer said softly, soothingly. “And I was deeply sorry to hear about his death. Now, tell me, what did you see?”

“I saw the hollow in the woods. I heard the horses coming, and I saw movement in the trees. And then the men stepped out, thin, haggard, like starving dogs. And starving dogs can be desperate. When the horses came, the men were ready to attack. And then … it was as if a fog suddenly settled over the daylight, but the mist was red, the color of the blood being spilled…. I saw … I saw them die. Some were shot, others skewered through by bayonets. Then I saw the riderless horses cantering away, and I saw the ground, strewn with the dead, one atop another, as if in death enemies had at last made amends.”

“Do you dream often?” he asked.

She longed to see the face of the man who had come to speak so kindly to her. “No.”

“But you have done so before?”

“Yes.”

“And when you have these dreams, what you see comes true?”

“Unless it is somehow stopped,” she said. “I tried so hard … but no one would listen.”

She was startled, but not frightened, when he took her hands.

His hands were very large, callused and clumsy, but warm, and offering great strength.

“She’s a Confederate spy,” someone muttered venomously.

“Gentleman, a spy does not warn the enemy in an attempt to prevent death,” he said. “A spy would let the enemy march to their doom. Tell me,” he said to her, “do you wish to bring us down?”

Darmowy fragment się skończył.