Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Book of Swords: Part 2»

Copyright

HarperVoyager

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2017

Copyright © 2017 by Gardner Dozois

Introduction © 2017 by Gardner Dozois

Individual story copyrights appear here

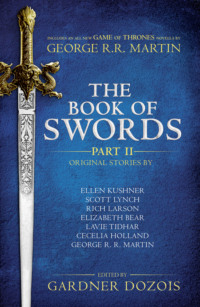

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

The author of each individual story asserts their moral rights, including the right to be identified as the author of their work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

These stories are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them are the work of the authors’ imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008274702

Ebook Edition © February 2018 ISBN: 9780008274733

Version: 2018-03-14

Copyright Acknowledgements

“When I Was a Highwayman” by Ellen Kushner. Copyright © 2017 by Ellen Kushner.

“The Smoke of Gold Is Glory” by Scott Lynch. Copyright © 2017 by Scott Lynch.

“The Colgrid Connundrum” by Rich Larson. Copyright © 2017 by Rich Larson.

“The King’s Evil” by Elizabeth Bear. Copyright © 2017 by Sarah Wishnevsky (Elizabeth Bear).

“Waterfalling” by Lavie Tidhar. Copyright © 2017 by Lavie Tidhar.

“The Sword Tyraste” by Cecelia Holland. Copyright © 2017 by Cecelia Holland.

“The Sons of the Dragon” by George R.R. Martin. Copyright © 2017 by George R.R. Martin.

Dedication

For George R.R. Martin, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, Robert E. Howard, C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, L. Sprague de Camp, Roger Zelazny, and all the other authors who ever wielded an imaginary sword, and for Kay McCauley, Anne Groell, and Sean Swanwick, for helping me bring this to you.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Copyright Acknowledgements

Dedication

Introduction by Gardner Dozois

When I Was a Highwayman by Ellen Kushner

The Smoke of Gold Is Glory by Scott Lynch

The Colgrid Conundrum by Rich Larson

The King’s Evil by Elizabeth Bear

Waterfalling by Lavie Tidhar

The Sword Tyraste by Cecelia Holland

The Sons of the Dragon by George R.R. Martin

About the Publisher

Introduction by Gardner Dozois

One day in 1963, I stopped in a drugstore on the way home from high school (at that point in time, spinner racks full of mass-market paperbacks in drugstores were one of the few places in our town where books were available; there was no actual bookstore), and spotted on the rack an anthology called The Unknown, edited by D. R. Bensen. I picked it up, bought it, and was immediately enthralled by it; it was the first anthology I ever bought, and a purchase that would have a long-term effect on my future career although I didn’t know that at the time. What it was was a collection of stories that Bensen had culled from the legendary (if short-lived) fantasy magazine Unknown, edited by equally legendary editor John W. Campbell, Jr., who at about the same time as he was revolutionizing science fiction as the editor of Astounding was revolutionizing fantasy in the pages of Astounding’s sister magazine Unknown from 1939 to 1943, when the magazine was killed by wartime paper shortages. In the early sixties, in a decade when the publishing industry was still coming out from under the shadow of postwar grim social realism, there was very little fantasy being published in a format affordable to purchase by a short-of-funds high-school student (except for the stories in genre magazines such as The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, which I didn’t know about at the time), and the rich harvest of different types of fantasy story available in Unknown was a revelation to me.

The story that had the biggest effect on me, though, was a bizarre, richly atmospheric story called “The Bleak Shore,” by Fritz Leiber, in which two seemingly mismatched adventurers, a giant swordsman from the icy North named Fafhrd and a sly, clever, nimble little man from the Southern climes called the Gray Mouser, are compelled to go on a doomed mission which seems destined to send them to their death (which fate, however, they cleverly avoid). It was a story unlike anything I’d ever read before, and I immediately wanted to read more stories like that.

Fortunately, it wasn’t long before I discovered another anthology on the drugstore spinner racks, Swords & Sorcery, edited by L. Sprague de Camp, this one not only containing another Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story, but dedicated entirely to the same kind of fantasy story, which I learned was called “Sword & Sorcery,” a name for the subgenre coined by Leiber himself; in the pages of this anthology, I read for the first time one of the adventures of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian and C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry, as well as stories by Poul Anderson, Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, and others. And I was hooked, becoming a lifelong fan of Sword & Sorcery, soon haunting used-book stores in what was then Scollay Square in Boston (now buried under the grim mass of Government Center), hunting through piles of moldering old pulp magazines for back issues of Unknown and Weird Tales that featured stories of Conan the Barbarian and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser and other swashbuckling heroes.

What I had blundered into was the first great revival of interest in Sword & Sorcery, a subgenre of fantasy that had at that point lain fallow for decades, with almost all of the material in those anthologies and those old pulp magazines having been published in the thirties or forties or even earlier, about the time that stories that took place in distinct fantasy worlds instead of seventeenth-century France or imaginary Central European countries began to precipitate out from the larger and older body of work about swashbuckling, sword-swinging adventurers written by authors such as Alexandre Dumas, Rafael Sabatini, Talbot Mundy, and Harold Lamb. After Edgar Rice Burroughs in A Princess of Mars and its many sequels sent adventurer John Carter to his own version of Mars, called Barsoom, to rescue princesses and have sword fights with giant four-armed Tharks, a closely parallel form to Sword & Sorcery sometimes called “Planetary Romance” or “Sword & Planet” stories developed, most prominently in the pages of pulp magazine Planet Stories between 1939 and 1955, with the two subgenres exchanging influences, and even many of the same authors, including authors such as C. L. Moore and Leigh Brackett, who were highly influential in both forms. The richly colored tales that made up Jack Vance’s classic The Dying Earth, also published about then, were also technically science fiction, but with their interdimensional intrusions, strange creatures, and mages who wielded what could either be looked at as magic or the highest of high technology, they could also function as fantasy as well.