Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

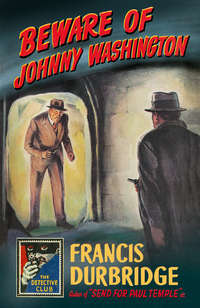

Czytaj książkę: «Beware of Johnny Washington: Based on ‘Send for Paul Temple’»

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by John Long Ltd 1951

'A Present for Paul' first published by the Yorkshire Evening Post 1946

Copyright © Estate of Francis Durbridge 1946, 1951

Introduction © Melvyn Barnes 2017

Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008242053

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008242046

Version: 2017-09-07

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

I. AN OBVIOUS CLUE

II. ENTER JOHNNY WASHINGTON

III. GREY MOOSE

IV. A JOB FOR THE POLICE

V. INQUISITIVE LADY

VI. A PRELIMINARY CONFERENCE

VII. A CALL FROM SCOTLAND YARD

VIII. LONDON BY THE SEA

IX. TALK OFF THE RECORD

X. RENDEZVOUS

XI. WHAT’S YOUR POISON?

XII. JOHNNY MAKES A SUGGESTION

XIII. AN UNEXPECTED PRESENT

XIV. A STRAIGHT TIP

XV. AN INFORMAL VISIT

XVI. BEHIND THE PANEL

XVII. THE SECRET TUNNEL

XVIII. ‘THE BEST LAID PLANS …’

XIX. A CASE OF ABDUCTION?

XX. EXIT VERITY GLYN?

XXI. MR QUINCE HAD A CLUE

XXII. THE ENEMY CAMP

XXIII. RUN TO EARTH

XXIV. THE DESERTED CAR

XXV. ‘RELEASE AT DAWN’

XXVI. THE END OF GREY MOOSE

POSTSCRIPT: A PRESENT FOR PAUL

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

FRANCIS Henry Durbridge (1912–1998) was arguably the most popular writer of mystery thrillers for BBC radio and television from the 1930s to the 1970s, after which he enjoyed a successful career as a stage dramatist. His radio serials are regularly repeated today, while his stage plays remain among the staple fare of amateur and professional theatre companies.

He was born in Kingston upon Hull and educated at Bradford Grammar School, Wylde Green College and Birmingham University, and as an undergraduate he began to pursue his schoolboy ambition to become a writer. Although he later worked briefly in a stockbroker’s office, his career as a full-time writer was assured by the BBC in the early 1930s when he responded to the broadcaster’s voracious appetite by providing comedy plays, children’s stories, musical libretti and numerous short sketches.

It was nevertheless his first two serious radio dramas, Promotion and Murder in the Midlands, that showed the sort of scriptwriting he particularly favoured. In 1938, at the age of twenty-five, he established himself in the crime fiction field when the BBC broadcast his serial Send for Paul Temple. Listeners ecstatically submitted over 7,000 requests for more, no doubt finding his light touch and characteristic ‘cliff-hangers’ a welcome distraction from worries about the gathering storm in Europe. Almost immediately Durbridge became one of the foremost writers of radio thrillers, with a prolific output that he further expanded by sometimes using the pseudonyms Frank Cromwell, Nicholas Vane and Lewis Middleton Harvey. To place him in context, in the mid-twentieth century his closest comparators were Edward J. Mason and Lester Powell (both coincidentally born the same year as Durbridge), together with Ernest Dudley, Alan Stranks and Philip Levene.

Send for Paul Temple was broadcast in eight episodes from 8 April to 27 May 1938. In this first case for the novelist-detective he meets newspaper reporter Steve Trent, who tells him that she has changed her name from Louise Harvey in order to pursue a gang of jewel thieves. The murder of her brother, a Scotland Yard man, unites Temple and Steve in their determination to unmask the Knave of Diamonds. That achieved, they create crime fiction history by deciding to marry—thus securing a quick return to the airwaves in Paul Temple and the Front Page Men in the autumn of 1938 and thereafter cementing their position as a mainstay of the BBC.

The early Paul Temple radio serials were adapted as books from the outset, but Durbridge’s first five novelisations were collaborations with another author because at that time he regarded himself as essentially a writer of dialogue, a scriptwriter rather than a novelist. Send for Paul Temple was published by John Long in June 1938, so it was presumably written while the radio serial was being broadcast and was intended to capitalise on the serial’s success. It was described in newspaper advertisements at the time as ‘the novel of the thriller that created a BBC fan-mail record’, and it was made Book of the Month by the Crime Book Society. The co-author was identified as John Thewes, although today it is widely believed that this was a pseudonym of Charles Hatton (who used his own name when collaborating on the next four Paul Temple novels). There is further evidence that Durbridge saw the wider potential of Send for Paul Temple, because he adapted it as a stage play produced in Birmingham in 1943 and also co-wrote the screenplay of the 1946 film version.

The Paul Temple serials proved to be Durbridge’s most enduring work for the radio, and they continued until 1968. One could easily assume that in the twenty-first century they might be regarded as passé, but today the Temples have been re-introduced to radio listeners through repeats of the surviving original recordings and new productions of the ‘lost’ serials, and there is a continuing market in printed books, e-books, CDs, DVDs and downloads. A new generation, together with those feeling nostalgic, can follow the exploits of the urbane detective who is constantly faced with bombs concealed in packages or booby-trapped ‘radiograms’, who deplores violence except in self-defence, and who never uses bad language but regularly utters the oath ‘By Timothy!’ The appeal seems undiminished, irrespective of the fact that the Durbridge milieu of Thames houseboats, expensive apartments, luxury sports cars and sophisticated cocktails must surely be alien to the lives of many among his present day audience.

The Temples were by no means the only protagonists created for radio audiences by Francis Durbridge. Among others was Johnny Washington, who appeared in eight episodes from 12 August to 30 September 1949 entitled Johnny Washington Esquire. This was not a serial, but a run of complete thirty-minute plays described as ‘the adventures of a gentleman of leisure’, with a young American scoring barely legal coups in Robin Hood style at the expense of London underworld characters. Of particular interest was the fact that Johnny was played by the Canadian actor Bernard Braden, who before his move to the UK had played the title role in the Canadian radio version of Send for Paul Temple in 1940.

Given Durbridge’s astuteness in maximising the commercial opportunities provided by his plot ideas, he would have wanted to get Johnny Washington Esquire into book form while its success on the radio was still fresh. His problem was that the radio series would be unsuitable as a novel, as it consisted of eight separate stories. The popular central character could nevertheless still be used in a full-length book, which resulted in John Long publishing Beware of Johnny Washington in April 1951.

Rather than produce a new and original novel, Durbridge took his 1938 book Send for Paul Temple and re-wrote it, with every character name changed and Johnny Washington instead of Paul Temple joining reporter Verity Glyn instead of Steve Trent in the hunt for her brother’s killer. In the ‘new’ book, Johnny is framed by a gang of criminals who leave visiting cards bearing his name on their crime scenes. Although usually an object of police suspicion, Johnny has to side reluctantly with the law in order to clear his name, protect the threatened Verity and identify the ruthless gang leader who calls himself Grey Moose.

So why did Durbridge re-cycle his earlier book in this way? It is unlikely that he was so dissatisfied with Send for Paul Temple that he made a purposeful attempt to improve upon it, because it had already achieved a classic status and had been reprinted several times (and indeed is still in print today). The obvious answer must surely be that Durbridge needed to use the Johnny Washington character before the name was forgotten, given the fact that he was to write no more Washington plays for the radio, and it was therefore necessary to act with the minimum of delay. It is also likely that he was trying to widen his appeal to the reading public, and was keen to secure recognition for more than his creation of the Temples. There could even have been a degree of insurance against the slim possibility that after five Paul Temple novels some readers might have begun to tire of them, which was one of the factors that from 1952 onwards encouraged Durbridge to create a brand of record-breaking television serials that deliberately excluded the Temples.

In the case of his novels, he was nevertheless careful to keep all his options open. Paul Temple books continued to appear from 1957 to 1988 (three were original and five were based on his radio serials); sixteen of his television serials were novelised between 1958 and 1982; and he wrote two stand-alone novels (Back Room Girl in 1950 and The Pig-Tail Murder in 1969) plus several novellas as newspaper serials. In addition it must be said that Beware of Johnny Washington was not the only example of re-cycling, as his novels Design for Murder (1951), Another Woman’s Shoes (1965) and Dead to the World (1967) were all originally Paul Temple radio serials that became non-Temple books with recycled plots—although only one of these, Beware of Johnny Washington, had also appeared as a separate Temple book.

In spite of its history, or perhaps because of it, Beware of Johnny Washington remains of considerable interest to Durbridge enthusiasts. It is a good solid thriller with many of the author’s typical elements and trademark twists and turns, written in a smooth and readable style that improves upon the slightly stilted early Temple novelisations. While it follows the storyline of Send for Paul Temple, it is more than just a straight transcription with new character names. Sub-plots are changed and developed, while Washington himself is given a personality and lifestyle that clearly distinguishes him from Temple.

Above all, unlike most of Durbridge’s other novels, Beware of Johnny Washington has not been available since its first publication over sixty-five years ago. For the host of Durbridge fans, that is a big attraction.

MELVYN BARNES

February 2017

CHAPTER I

AN OBVIOUS CLUE

‘ANOTHER gelignite job,’ said Chief Inspector Kennard, folding his arms and gazing moodily through the tall window of the deputy commissioner’s office.

‘Eight thousand pounds’ worth of diamonds,’ added Superintendent Locksley in a worried tone. ‘Gloucester this time—we never know where they’ll turn up next.’

The Deputy Commissioner, Sir Robert Hargreaves, pulled a stack of variously coloured folders towards him and selected a grey one. For a minute or two he thumbed over the papers without speaking. His subordinates eyed each other a trifle uncomfortably and waited for him to speak.

They watched him turn over one report after another, scanning them briefly and stopping twice to make a pencilled note on the pad at his elbow. Meanwhile, the cigarette he had been smoking slowly burnt on the ash-tray beside him.

A man in his late fifties, Sir Robert had attained his present position by a reputation for his capacity to digest facts rapidly and methodically and, having done so, to arrive at a rapid decision which usually proved to be the right one.

The smoke from the chief’s cigarette tickled Locksley’s nose and he felt a sudden craving to light one himself, but would not dare to do so without Sir Robert’s invitation. There was an air of discipline about this plainly furnished office which one did not associate with tea-drinking and cigarettes. When you went to see Sir Robert you gave him your information, received his instructions, and left to put them into operation.

However, the gelignite robberies were in a class of their own and on a scale that had not been encountered at the Yard for some years. A lorry load of gelignite which had been dispatched to the scene of some mining operations in Cornwall had never arrived at its destination, though the driver was discovered lying senseless at the side of the road in the early hours of the morning. All he remembered was climbing into his cab after calling at an all-night pull-up near Taunton, and receiving a blow on the head which resulted in slight concussion. He had not even caught a glimpse of his assailant.

A week later, the safe at a large super cinema at Norwich was blown open with gelignite, and the week’s takings, amounting to about one thousand five hundred pounds, were stolen. This was presumably in the nature of a try-out, for the gelignite gang almost immediately went after bigger game. They began with a jeweller’s safe in Birmingham, which yielded over five thousand pounds’ worth of diamonds, pearls and platinum settings. After Birmingham came Leicester, Sheffield, Oldham and Shrewsbury. The aggregate value of the stolen goods was now in the region of five figures.

The deputy commissioner looked up from the report of the raid on the Gloucester jewellers, which he had been scanning carefully.

‘What about this night watchman?’ he inquired.

‘I’m afraid he’s dead, sir,’ replied Locksley. ‘He was pretty heavily chloroformed and according to the doctor his heart was in a bad state to stand up to any sudden shock.’

Sir Robert frowned.

‘This is getting extremely serious,’ he murmured. ‘We shall have the papers playing it up worse than ever; then some damn fool will be asking a question in the House. Was this night watchman above board?’

Locksley shook his head.

‘I’m afraid not, sir. He’d only been with the firm about a month. He joined them under the name of Brookfield, but we soon found he had a long record as Wilfred Hiller, alias Burns. Everything from petty thefts to smash and grab.’

‘Humph! He might have been part of the set-up,’ grunted Sir Robert. ‘Pity they gave him an overdose …’

‘It was one way to make sure he didn’t talk—and to avoid paying him his cut,’ Kennard pointed out quietly.

Sir Robert nodded. ‘Who was in charge down there?’ he asked.

‘Inspector Dovey had already arrived when we got there—you remember we recalled him from the Special Branch to work on the gelignite jobs,’ replied Locksley. ‘He was questioning the constable who had discovered the robbery, a young man named Roscoe. Roscoe’s only been in the force two years, but he’s quite a good record. He was apparently passing the jewellers on his beat and noticed that the side door was open a couple of inches, so he went in to investigate.’

‘What about fingerprints?’

‘Nothing we can trace, except Hiller, the night watchman’s, and they were nowhere near the safe,’ replied Locksley. ‘It was the same on all the other jobs. There’s somebody running the outfit who knows his way around.’

Sir Robert shrugged and went on reading the report, a tiny furrow deepening between his eyebrows, and his lips tightening into a thin line.

‘What did Dovey have to say?’ he inquired at length.

Kennard smiled. ‘He didn’t seem to know whether he was coming or going. Talked about a large criminal organization—I think he’s been meeting too many international spies.’ A note of contempt in his voice prompted Hargreaves to ask:

‘Then you don’t think it is a criminal organization?’

Kennard shook his head most decisively, a flicker of a grin around his thin mouth.

‘We’re always reading about these big criminal set-ups,’ he said sarcastically, ‘but I’ve been with the police here and abroad for over fifteen years without coming across a sign of any really elaborate organization. Crooks don’t work that way; it’s every man for himself and to hell with the one who’s caught. Of course, we had the racecourse gangs a few years back, but that was different—not what you’d call scientifically planned crime. If you ask me, these jobs have been pulled by a little bunch of old lags.’

Sir Robert swung round in his chair and stubbed out his cigarette.

‘What do you think, Locksley?’ he demanded. The superintendent glanced across at his colleague and shifted somewhat uncomfortably in his chair.

‘I’m afraid I don’t agree with Kennard, Sir Robert,’ he admitted at last. The inspector looked startled for a moment and appeared to be about to make some comment, but he changed his mind, and Locksley went on: ‘I thought the same as Kennard for some time, but I’ve come to the conclusion this last week or so that these jobs are being planned to the last detail by some mentality far and away above that of the average crook.’

Hargreaves gave no sign as to whether he was impressed by this argument, other than by making a brief note on his pad.

‘Did you see the night watchman before he died?’ he asked. Locksley nodded.

‘Yes, sir. He was in pretty bad shape, of course, and I thought he wouldn’t be able to say anything. But the doctor gave him an injection, and he seemed to recover consciousness.’

‘Well, what did he say?’ urged Hargreaves with a note of impatience in his tone.

The superintendent rubbed his hands rather nervously.

‘I couldn’t be quite sure, sir,’ he replied dubiously, ‘but it sounded to me rather like “Grey Moose”.’

There was a sound of suppressed chuckle from Kennard, but the deputy commissioner was quickly turning through his file.

‘Here we are,’ he said suddenly. ‘A report on the Oldham case—you remember Smokey Pearce died rather mysteriously soon after. He was run over by a lorry—found by a constable on the Preston road—there was an empty jewel case on him from the Oldham shop.’

‘That’s right, sir,’ said Kennard. ‘But we couldn’t get him to talk …’

‘Wait,’ said Hargreaves. ‘He did manage to get out a couple of words before he passed out … “Grey Moose”.’

‘The same words exactly,’ said Locksley, his eyes lighting up. ‘But what the devil do they mean? It might be a brand of pressed beef—’

‘Or one of these American cigarettes,’ put in Kennard.

Hargreaves waved aside these interruptions.

‘It must mean something,’ he insisted. ‘Two dying men don’t speak the same words exactly just by coincidence.’

Locksley nodded slowly.

‘I see what you’re driving at, sir,’ he said. ‘You think these two were in on those jobs, and the gang wiped ’em out so as to take no chances of their giving the game away. They sound a pretty callous lot of devils.’

‘I should say that it’s the head of this organization who is behind these—er—liquidations,’ mused Sir Robert. ‘They are quite obviously part and parcel of his plans.’

‘Then you agree with Locksley that there is an organization,’ queried Kennard abruptly.

Sir Robert rubbed his forehead rather wearily with his left hand while he continued to turn over reports with his right. At last, he closed the folder.

‘That seems to be the only conclusion, Inspector,’ he said, with a sigh. ‘If they were just the usual small-time safe-busters, like Peter Scales, or “Mo” Turner or Larry the Canner, the odds are we’d have got one or more of them by now. They’d try to get rid of the stuff through one of the fences we’ve got tabs on, and we’d be on to them. But the head of this crowd has obviously his own special means of disposal.’

‘That’s true,’ agreed Locksley. ‘We haven’t traced a single item in all those jobs yet.’

‘He could be holding on to the stuff till it cools down,’ suggested Kennard.

‘I shouldn’t imagine that’s very likely,’ said the deputy commissioner, thoughtfully tracing a design on his blotting pad with his paper-knife. ‘I can’t help agreeing with Locksley that we’re up against something really big, and we’ve got to pull every shot out of the locker. Now, are you absolutely sure there was nothing about the Gloucester job that might give us something to go on?’

He looked from one to the other and there was silence for a few seconds. Then Locksley slowly took a bulging wallet from his inside pocket and extracted a small piece of paste-board about half the size of a postcard.

‘There was this card,’ he said, in a doubtful tone.

Sir Robert took the card and examined it carefully.

‘Where did you find it?’ he asked.

‘In the waste-paper basket just by the safe at the Gloucester jewellers. As you see, it was torn into five pieces, but it wasn’t difficult to put it together.’

Sir Robert picked up a magnifying glass and placed the card under it. On the card was printed in imitation copperplate handwriting:

With the compliments of Johnny Washington.

‘So that joker from America has popped up again,’ murmured Sir Robert. ‘Where’s the catch this time?’

During the past year or so, Scotland Yard had come to know this strange young man from America, with the mobile features, rimless glasses and ingenuous smile rather too well. For the presence of Johnny Washington usually meant trouble for somebody. As often as not, it was for some unscrupulous operator either inside or on the verge of the underworld, but the police were usually none too pleased about it, for the matter invariably entailed a long and complicated prosecution, even when Mr Washington had presented them with indisputable evidence. And what particularly annoyed the police was the fact that Johnny Washington always emerged as debonair and unruffled as ever, and often several thousand dollars to the good. The Yard chiefs had experienced a pronounced sensation of relief when Johnny had informed them that he had bought a small manor house not far from Sevenoaks, and proposed to devote his energies to collecting pewter and playing the country squire.

‘Where’s the catch?’ repeated Sir Robert, turning the card over and peering at it again.

‘In the first place,’ replied Locksley, ‘Johnny says he has never set foot in Gloucester in his life.’

‘Well, you know what a confounded liar the fellow is,’ retorted Hargreaves. ‘Have you checked on him at all?’

‘The jewellers say they have never set eyes on him,’ said Locksley.

‘I don’t suppose they’ve set eyes on any of the gang that did the job,’ grunted the commissioner. ‘Did you find out if he had an alibi?’

‘Yes, he had an alibi all right. He was up in Town for the night to see a girl named Candy Dimmott in a new musical—seems he knew her in New York. He stayed at the St Regis—got in soon after midnight. According to the doctor, the night watchman had been chloroformed about that time—and the constable found him soon after 2 a.m. So Washington simply couldn’t have been in Gloucester then.’

‘You never can tell with that customer,’ said Kennard dubiously.

‘I questioned the night porter at the St Regis—he knows Washington well, and swears he never left the place while he was on duty,’ said Locksley. He turned to his chief again. ‘There’s another thing about that card, sir.’

‘Eh? What’s that?’

‘There are no fingerprints on it. I used rubber gloves when I put it together, and whoever tore it up and put it in that waste-paper basket must have done the same. Now, if Mr Washington left that card deliberately, why should he go to the trouble of using gloves?’

‘He might have been wearing them anyhow,’ pointed out Kennard.

Locksley shrugged.

‘Yet again, if he wanted to leave a card, why tear it up?’ he demanded earnestly.

Sir Robert rested his chin on his hand and gazed thoughtfully at the fire.

‘I begin to see what you’re driving at,’ he murmured. ‘You think this card business is a plant—presumably to distract attention from the real master mind.’

‘That’s about it, sir,’ agreed Locksley. ‘Washington’s name has been in the papers several times—and there was that silly article about Johnny being the modern Robin Hood. It’s given somebody an idea.’

Sir Robert picked up a wire paper fastener and very deliberately clipped the card to the report of the Gloucester robbery.

‘You haven’t seen Washington?’ he asked.

‘No, sir. I spoke to him twice on the telephone. He seemed a bit surprised, then amused. But he helped me all he could about the alibi when he saw how serious it was.’

‘Alibi or not, I think we should keep an eye on that gentleman,’ suggested Kennard.

‘That sounds like a good idea,’ replied Hargreaves. ‘You know him fairly well, don’t you, Locksley?’

‘I certainly saw something of him in the Blandford case.’

‘All right, then you can pop down to his place and have a talk to him as soon as you can get away from here today. And if you get the slightest hint that he is the brains behind this gang, don’t take any chances. Just tell him you are rechecking his alibi.’

‘It isn’t easy to fool Johnny Washington,’ said Locksley, slipping his little black notebook back into his inside pocket.

‘I must say, sir, I’m not convinced that it is a real organization we’re up against,’ insisted Kennard. ‘What makes you so sure about that?’

Sir Robert began to pace up and down between his desk and the fireplace.

‘It’s more a hunch than anything,’ he confessed. ‘For one thing, they’ve tackled such a variety of jobs—the average safe-buster sticks to one line as a rule and goes after the sort of stuff he can get rid of without much trouble. This gelignite gang have already robbed a cinema, a bank, two jewellers and a factory office. It takes a very unusual brain to plan such a variety of jobs in a comparatively short time.’

‘A brain like Johnny Washington’s?’ queried Kennard.

Sir Robert Hargreaves did not reply.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.