Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

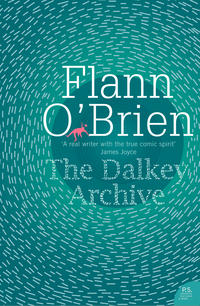

Czytaj książkę: «The Dalkey Archive»

FLANN O’BRIEN

The Dalkey Archive

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

This Harper Perennial Modern Classics edition published 2007

Previously published in paperback by Grafton in 1986 (reprinted once), Paladin 1990 and as a Flamingo Modern Classic in 1993 (reprinted 10 times)

First published in Great Britain by MacGibbon & Kee Ltd 1964

Copyright © Brian O’Nolan 1964

PS Section copyright © Richard Shephard 2007

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007247196

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2016 ISBN 9780007405893

Version: 2016-03-31

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication

I dedicate these pages to my Guardian Angel, impressing upon him that I’m only fooling and warning him to see to it that there is no misunderstanding when I go home.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Keep Reading

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features …

About the Author

About the Author(s)

The Dalkey Archive: Not So Much an Encore as a Rehearsal

About the Book

Re: Joyce

A Dalkey Drama

Joyce: Portraits of the Artist as a Fictional Character

Read On

If You Loved This, You Might Like …

Flann O’Brien Trivia

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

1

Dalkey is a little town maybe twelve miles south of Dublin, on the shore. It is an unlikely town, huddled, quiet, pretending to be asleep. Its streets are narrow, not quite self-evident as streets and with meetings which seem accidental. Small shops look closed but are open. Dalkey looks like an humble settlement which must, a traveller feels, be next door to some place of the first importance and distinction. And it is – vestibule of a heavenly conspection.

Behold it. Ascend a shaded, dull, lane-like way, per iter, as it were, tenebricosum, and see it burst upon you as if a curtain had been miraculously whisked away. Yes, the Vico Road.

Good Lord!

The road itself curves gently upward and over a low wall to the left by the footpath enchantment is spread – rocky grassland falling fast away to reach a toy-like railway far below, with beyond it the immeasurable immanent sea, quietly moving slowly in the immense expanse of Killiney Bay. High in the sky which joins it at a seam far from precise, a caravan of light cloud labours silently to the east.

And to the right? Monstrous arrogance: a mighty shoulder of granite climbing ever away, its overcoat of furze and bracken embedded with stern ranks of pine, spruce, fir and horse-chestnut, with further on fine clusters of slim, meticulous eucalyptus – the whole a dazzle of mildly moving leaves, a farrago of light, colour, haze and copious air, a wonder that is quite vert, verdant, vertical, verticillate, vertiginous, in the shade of branches even vespertine. Heavens, has something escaped from the lexicon of Sergeant Fottrell?

But why this name Vico Road? Is there to be recalled in this magnificence a certain philosopher’s pattern of man’s lot on earth – thesis, antithesis, synthesis, chaos? Hardly. And is this to be compared with the Bay of Naples? That is not to be thought of, for in Naples there must be heat and hardness belabouring desiccated Italians – no soft Irish skies, no little breezes that feel almost coloured.

At a great distance ahead and up, one could see a remote little obelisk surmounting some steps where one can sit and contemplate all this scene: the sea, the peninsula of Howth across the bay and distantly, to the right, the dim outline of the Wicklow mountains, blue or grey. Was the monument erected to honour the Creator of all this splendour? No. Perhaps in remembrance of a fine Irish person He once made – Johannes Scotus Erigena, perhaps, or possibly Parnell? No indeed: Queen Victoria.

Mary was nudging Michael Shaughnessy. She loitered enticingly about the fringes of his mind; the deep brown eyes, the light hair, the gentleness yet the poise. She was really a nuisance yet never far away. He frowned and closed his fist, but intermittent muttering immediately behind him betokened that Hackett was there.

– How is she getting on, he asked, drawing level, that pious Mary of yours?

It was by no means the first time that this handsome lout had shown his ability to divine thought, a nasty gift.

– Mind your own business, Shaughnessy said sourly. I never ask about the lady you call Asterisk Agnes.

– If you want to know, she’s very well, thank you.

They walked in, loosely clutching their damp bathing things.

In the low seaward wall there was a tiny gap which gave access to a rough downhill path towards the railway far below; there a footbridge led to a bathing place called White Rock. At this gap a man was standing, supporting himself somewhat with a hand on the wall. As Shaughnessy drew near he saw the man was spare, tall, clean-shaven, with sparse fairish hair combed sideways across an oversize head.

– This poor bugger’s hurt, Hackett remarked.

The man’s face was placid and urbane but contorted in a slight grimace. He was wearing sandals and his right foot in the region of the big toe was covered with fresh blood. They stopped.

– Are you hurt, sir? Hackett asked.

The man politely examined each of them in turn.

– I suppose I am, he replied. There are notices down there about the dangers of the sea. Usually there is far more danger on land. I bashed my right toes on a sharp little dagger of granite I didn’t see on that damned path.

– Perhaps we could help, Shaughnessy said. We’d be happy to assist you down to the Colza Hotel in Dalkey. We could get you a chemist there or maybe a doctor.

The man smiled slightly.

– That’s good of you, he replied, but I’m my own doctor. Perhaps though you could give me a hand to get home?

– Well, certainly, Shaughnessy said.

– Do you live far, sir? Hackett asked.

– Just up there, the man said, pointing to the towering trees. It’s a stiff climb with a cut foot.

Shaughnessy had no idea that there was any house in the fastness pointed to, but almost opposite there was a tiny gate discernible in the rough railing bounding the road.

– So long as you’re sure there is a house there, Hackett said brightly, we will be honoured to be of valuable succour.

– The merit of the house is that hardly anybody except the postman knows it’s there, the other replied agreeably.

They crossed the road, the two escorts lightly assisting at each elbow. Inside the gate a narrow but smooth enough pathway fastidiously picked its way upward through treetrunks and shrubs.

– Might as well introduce myself, the invalid said. My name’s De Selby.

Shaughnessy gave his, adding that everybody called him Mick. He noticed that Hackett styled himself just Mr Hackett: it seemed an attitude of polite neutrality, perhaps condescension.

– This part of the country, De Selby remarked, is surprisingly full of tinkers, gawms and gobshites. Are you gentlemen skilled in the Irish language?

The non-sequitur rather took Shaughnessy aback, but not Hackett.

– I know a great lot about it, sir. A beautiful tongue.

– Well, the word mór means big. In front of my house – we’re near it now – there is a lawn surprisingly large considering the terrain. I thought I would combine mór and lawn as a name for the house. A hybrid, of course, but what matter? I found a looderamawn in Dalkey village by the name of Teague McGettigan. He’s the loçal cabman, handyman, and observer of the weather; there is absolutely nothing he can’t do. I asked him to paint the name on the gate, and told him the words. Now wait till you see the result.

The house could now be glimpsed, a low villa of timber and brick. As they drew nearer De Selby’s lawn looked big enough but regrettably it was a sloping expanse of coarse, scruffy grass embroidered with flat weeds. And in black letters on the wooden gate was the title: LAWNMOWER. Shaughnessy and Hackett sniggered as De Selby sighed elaborately.

– Well the dear knows I always felt that Teague was our domestic Leonardo, Hackett chuckled. I’m well acquainted with the poor bastard.

They sidled gently inward. De Selby’s foot was now dirty as well as bloody.

2

Our mutilated friend seems a decent sort of segotia, Hackett remarked from his armchair. De Selby had excused himself while he attended to ‘the medication of my pedal pollex’, and the visitors gazed about his living room with curiosity. It was oblong in shape, spacious, with a low ceiling. Varnished panelling to the height of about eighteen inches ran right round the walls, which otherwise bore faded greenish paper. There were no pictures. Two heavy mahogany bookcases, very full, stood in embrasures to each side of the fireplace, with a large press at the blank end of the room. There were many chairs, a small table in the centre and by the far wall a biggish table bearing sundry scientific instruments and tools, including a microscope. What looked like a powerful lamp hovered over this and to the left was an upright piano by Liehr, with music on the rest. It was clearly a bachelor’s apartment but clean and orderly. Was he perhaps a musician, a medical man, a theopneust, a geodetic chemist … a savant?

– He’s snug here anyway, Mick Shaughnessy said, and very well hidden away.

– He’s the sort of man, Hackett replied, that could be up to any game at all in this sort of secret HQ. He might be a dangerous character.

Soon De Selby re-appeared, beaming, and took his place in the centre, standing with his back to the empty fireplace.

– A superficial vascular lesion, he remarked pleasantly, now cleansed, disinfected, anointed, and with a dressing you see which is impenetrable even by water.

– You mean, you intend to continue swimming? Hackett asked.

– Certainly.

– Bravo! Good man.

– Oh not at all – it’s part of my business. By the way, would it be rude to enquire what is the business of you gentlemen?

– I’m a lowly civil servant, Mick replied. I detest the job, its low atmosphere and the scruff who are my companions in the office.

– I’m worse off, Hackett said in mock sorrow. I work for the father, who’s a jeweller but a man that’s very careful with the keys. No opportunity of giving myself an increase in pay. I suppose you could call me a jeweller too, or perhaps a sub-jeweller. Or a paste jeweller.

– Very interesting work, for I know a little about it. Do you cut stones?

– Sometimes.

– Yes. Well I’m a theologist and a physicist, sciences which embrace many others such as eschatology and astrognosy. The peace of this part of the world makes true thinking possible. I think my researches are nearly at an end. But let me entertain you for a moment.

He sat down at the piano and after some slow phrases, erupted into what Mick with inward wit, would dub a headlong chromatic dysentery which was ‘brilliant’ in the bad sense of being inchoate and, to his ear at least, incoherent. A shattering chord brought the disorder to a close.

– Well, he said, rising, what did you think of that?

Hackett looked wise.

– I think I detected Liszt in one of his less guarded moments, he said.

– No, De Selby answered. The basis of that was the canon at the start of César Franck’s well-known sonata for violin and piano. The rest was all improvisation. By me.

– You’re a splendid player, Mick ventured archly.

– It’s only for amusement but a piano can be a very useful instrument. Wait till I show you something.

He returned to the instrument, lifted half of the hinged top and took out a bottle of yellowish liquid, which he placed on the table. Then opening a door in the nether part of a bookcase, he took out three handsome stem glasses and a decanter of what looked like water.

– This is the best whiskey to be had in Ireland, faultlessly made and perfectly matured. I know you will not refuse a taiscaun.

– Nothing would make me happier, Hackett said. I notice that there’s no label on the bottle.

– Thank you, Mick said, accepting a generous glass from De Selby. He did not like whiskey much, or any intoxicant, for that matter. But manners came first. Hackett followed his example.

– The water’s there, De Selby gestured. Don’t steal another man’s wife and never water his whiskey. No label on the bottle? True. I made that whiskey myself.

Hackett had taken a tentative sip.

– I hope you know that whiskey doesn’t mature in a bottle. Though I must say that this tastes good.

Mick and De Selby took a reasonable gulp together.

– My dear fellow, De Selby replied, I know all about sherry casks, temperature, subterranean repositories and all that extravaganza. But such considerations do not arise here. This whiskey was made last week.

Hackett leaned forward in his chair, startled.

– What was that? he cried. A week old? Then it can’t be whiskey at all. Good God, are you trying to give us heart failure or dissolve our kidneys?

De Selby’s air was one of banter.

– You can see, Mr Hackett, that I am also drinking this excellent potion myself. And I did not say it was a week old. I said it was made last week.

– Well, this is Saturday. We needn’t argue about a day or two.

– Mr De Selby, Mick interposed mildly, it is clear enough that you are making some distinction in what you said, that there is some nicety of terminology in your words. I can’t quite follow you.

De Selby here took a drink which may be described as profound and then suddenly an expression of apocalyptic solemnity came over all his mild face.

– Gentlemen, he said, in an empty voice, I have mastered time. Time has been called, an event, a repository, a continuum, an ingredient of the universe. I can suspend time, negative its apparent course.

Mick thought it funny in retrospect that Hackett here glanced at his watch, perhaps involuntarily.

– Time is still passing with me, he croaked.

– The passage of time, De Selby continued, is calculated with reference to the movements of the heavenly bodies. These are fallacious as determinants of the nature of time. Time has been studied and pronounced upon by many apparently sober men – Newton, Spinoza, Bergson, even Descartes. The postulates of the Relativity nonsense of Einstein are mendacious, not to say bogus. He tried to say that time and space had no real existence separately but were to be apprehended only in unison. Such pursuits as astronomy and geodesy have simply befuddled man. You understand?

As it was at Mick he looked the latter firmly shook his head but thought well to take another stern sup of whiskey. Hackett was frowning. De Selby sat down by the table.

– Consideration of time, he said, from intellectual, philosophic or even mathematical criteria is fatuity, and the pre-occupation of slovens. In such unseemly brawls some priestly fop is bound to induce a sort of cerebral catalepsy by bringing forward terms such as infinity and eternity.

Mick thought it seemly to say something, however foolish.

– If time is illusory as you seem to suggest, Mr De Selby, how is it that when a child is born, with time he grows to be a boy, then a man, next an old man and finally a spent and helpless cripple?

De Selby’s slight smile showed a return of the benign mood.

– There you have another error in formulating thought. You confound time with organic evolution. Take your child who has grown to be a man of twenty-one. His total life-span is to be seventy years. He has a horse whose life-span is to be twenty. He goes for a ride on his horse. Do these two creatures subsist simultaneously in dissimilar conditions of time? Is the velocity of time for the horse three and a half times that for the man?

Hackett was now alert.

– Come here, he said. That greedy fellow the pike is reputed to grow to be up to two hundred years of age. How is our time-ratio if he is caught and killed by a young fellow of fifteen?

– Work it out for yourself, De Selby replied pleasantly. Divergences, incompatibilities, irreconcilables are everywhere. Poor Descartes! He tried to reduce all goings-on in the natural world to a code of mechanics, kinetic but not dynamic. All motion of objects was circular, he denied a vacuum was possible and affirmed that weight existed irrespective of gravity. Cogito ergo sum? He might as well have written inepsias scripsi ergo sum and prove the same point, as he thought.

– That man’s work, Mick interjected, may have been mistaken in some conclusions but was guided by his absolute belief in Almighty God.

– True indeed. I personally don’t discount the existence of a supreme supra mundum power but I sometimes doubted if it is benign. Where are we with this mess of Cartesian methodology and Biblical myth-making? Eve, the snake and the apple. Good Lord!

– Give us another drink if you please, Hackett said. Whiskey is not incompatible with theology, particularly magic whiskey that is ancient and also a week old.

– Most certainly, said De Selby, rising and ministering most generously to the three glasses. He sighed as he sat down again.

– You men, he said, should read all the works of Descartes, having first thoroughly learnt Latin. He is an excellent example of blind faith corrupting the intellect. He knew Galileo, of course, accepted the latter’s support of the Copernican theory that the earth moves round the sun and had in fact been busy on a treatise affirming this. But when he heard that the Inquisition had condemned Galileo as a heretic, he hastily put away his manuscript. In our modern slang he was yellow. And his death was perfectly ridiculous. To ensure a crust for himself, he agreed to call on Queen Christina of Sweden three times a week at five in the morning to teach her philosophy. Five in the morning in that climate! It killed him, of course. Know what age he was?

Hackett had just lit a cigarette without offering one to anybody.

– I feel Descartes’ head was a little bit loose, he remarked ponderously, not so much for his profusion of erroneous ideas but for the folly of a man of eighty-two thus getting up at such an unearthly hour and him near the North Pole.

– He was fifty-four, De Selby said evenly.

– Well by damn, Mick blurted, he was a remarkable man however crazy his scientific beliefs.

– There’s a French term I heard which might describe him, Hackett said. Idiot-savant.

De Selby produced a solitary cigarette of his own and lit it. How had he inferred that Mick did not smoke?

– At worst, he said in a tone one might call oracular, Descartes was a solipsist. Another weakness of his was a liking for the Jesuits. He was very properly derided for regarding space as a plenum. It is a coincidence, of course, but I have made the parallel but undoubted discovery that time is a plenum.

– What does that mean? Hackett asked.

– One might describe a plenum as a phenomenon or existence full of itself but inert. Obviously space does not satisfy such a condition. But time is a plenum, immobile, immutable, ineluctable, irrevocable, a condition of absolute stasis. Time does not pass. Change and movement may occur within time.

Mick pondered this. Comment seemed pointless. There seemed no little straw to clutch at; nothing to question.

– Mr De Selby, he ventured at last, it would seem impertinent of the like of me to offer criticism or even opinions on what I apprehend as purely abstract propositions. I’m afraid I harbour the traditional idea and experience of time. For instance, if you permit me to drink enough of this whiskey, by which I mean too much, I’m certain to undergo unmistakable temporal punishment. My stomach, liver and nervous system will be wrecked in the morning.

– To say nothing of the dry gawks, Hackett added. De Selby laughed civilly.

– That would be a change to which time, of its nature, is quite irrelevant.

– Possibly, Hackett replied, but that academic observation will in no way mitigate the reality of the pain.

– A tincture, De Selby said, again rising with the bottle and once more adding generously to the three glasses. You must excuse me for a moment or two.

Needless to say, Hackett and Mick looked at each other in some wonder when he had left the room.

– This malt seems to be superb, Hackett observed, but would he have dope or something in it?

– Why should there be? He’s drinking plenty of it himself.

– Maybe he’s gone away to give himself a dose of some antidote. Or an emetic.

Mick shook his head genuinely.

– He’s a strange bird, he said, but I don’t think he’s off his head, or a public danger.

– You’re certain he’s not derogatory?

– Yes. Call him eccentric.

Hackett rose and gave himself a hasty extra shot from the bottle, which in turn Mick repelled with a gesture. He lit another cigarette.

– Well, he said, I suppose we should not overstay our welcome. Perhaps we should go. What do you say?

Mick nodded. The experience had been curious and not to be regretted; and it could perhaps lead to other interesting things or even people. How commonplace, he reflected, were all the people he did know.

When De Selby returned he carried a tray with plates, knives, a dish of butter and an ornate basket full of what seemed golden bread.

– Sit in to the table, lads – pull over your chairs, he said. This is merely what the Church calls a collation. These delightful wheaten farls were made by me, like the whiskey, but you must not think I’m like an ancient Roman emperor living in daily fear of being poisoned. I’m alone here, and it’s a long painful pilgrimage to the shops.

With a murmur of thanks the visitors started this modest and pleasant meal. De Selby himself took little and seemed preoccupied.

– Call me a theologian or a physicist as you will, he said at last rather earnestly, but I am serious and truthful. My discoveries concerning the nature of time were in fact quite accidental. The objective of my research was altogether different. My aim was utterly unconnected with the essence of time.

– Indeed? Hackett said rather coarsely as he coarsely munched. And what was the main aim?

– To destroy the whole world.

They stared at him. Hackett made a slight noise but De Selby’s face was set, impassive, grim.

– Well, well, Mick stammered.

– It merits destruction. Its history and prehistory, even its present, is a foul record of pestilence, famine, war, devastation and misery so terrible and multifarious that its depth and horror are unknown to any one man. Rottenness is universally endemic, disease is paramount. The human race is finally debauched and aborted.

– Mr De Selby, Hackett said with a want of gravity, would it be rude to ask just how you will destroy the world? You did not make it.

– Even you, Mr Hackett, have destroyed things you did not make. I do not care a farthing about who made the world or what the grand intention was, laudable or horrible. The creation is loathsome and abominable, and total extinction could not be worse.

Mick could see that Hackett’s attitude was provoking brusqueness whereas what was needed was elucidation. Even marginal exposition by De Selby would throw light on the important question – was he a true scientist or just demented?

– I can’t see, sir, Mick ventured modestly, how this world could be destroyed short of arranging a celestial collision between it and some other great heavenly body. How a man could interfere with the movements of the stars – I find that an insoluble puzzle, sir.

De Selby’s taut expression relaxed somewhat.

– Since our repast is finished, have another drink, he said, pushing forward the bottle. When I mentioned destroying the whole world, I was not referring to the physical planet but to every manner and manifestation of life on it. When my task is accomplished – and I feel that will be soon – nothing living, not even a blade of grass, a flea – will exist on this globe. Nor shall I exist myself, of course.

– And what about us? Hackett asked.

– You must participate in the destiny of all mankind, which is extermination.

– Guesswork is futile, Mr De Selby, Mick murmured, but could this plan of yours involve liquefying all the ice at the Poles and elsewhere and thus drowning everything, in the manner of the Flood in the Bible?

– No. The story of that Flood is just silly. We are told it was caused by a deluge of forty days and forty nights. All this water must have existed on earth before the rain started, for more can not come down than was taken up. Commonsense tells me that this is childish nonsense.

– That is merely a feeble rational quibble, Hackett cut in. He liked to show that he was alert.

– What then, sir, Mick asked in painful humility, is the secret, the supreme crucial secret?

De Selby gave a sort of grimace.

– It would be impossible for me, he explained, to give you gentlemen, who have no scientific training, even a glimpse into my studies and achievements in pneumatic chemistry. My work has taken up the best part of a life-time and, though assistance and co-operation were generously offered by men abroad, they could not master my fundamental postulate: namely, the annihilation of the atmosphere.

– You mean, abolish air? Hackett asked blankly.

– Only its biogenic and substantive ingredient, replied De Selby, which, of course, is oxygen.

– Thus, Mick interposed, if you extract all oxygen from the atmosphere or destroy it, all life will cease?

– Crudely put, perhaps, the scientist agreed, now again genial, but you may grasp the idea. There are certain possible complications but they need not trouble us now.

Hackett had quietly helped himself to another drink and showed active interest.

– I think I see it, he intoned. Exit automatically the oxygen and we have to carry on with what remains, which happens to be poison. Isn’t it murder though?

De Selby paid no attention.

– The atmosphere of the earth, meaning what in practice we breathe as distinct from rarefied atmosphere at great heights, is composed of roughly 78 per cent nitrogen, 21 oxygen, tiny quantities of argon and carbon dioxide, and microscopic quantities of other gases such as helium and ozone. Our preoccupation is with nitrogen, atomic weight 14.008, atomic number 7.

– Is there a smell off nitrogen? Hackett enquired.

– No. After extreme study and experiment I have produced a chemical compound which totally eliminates oxygen from any given atmosphere. A minute quantity of this hard substance, small enough to be invisible to the naked eye, would thus convert the interior of the greatest hall on earth into a dead world provided, of course, the hall were properly sealed. Let me show you.

He quietly knelt at one of the lower presses and opened the door to reveal a small safe of conventional aspect. This he opened with a key, revealing a circular container of dull metal of a size that would contain perhaps four gallons of liquid. Inscribed on its face were the letters DMP.

– Good Lord, Hackett cried, the DMP! The good old DMP! The grandfather was a member of that bunch.

De Selby turned his head, smiling bleakly.

– Yes – the DMP – the Dublin Metropolitan Police. My own father was a member. They are long-since abolished, of course.

– Well what’s the idea of putting that on your jar of chemicals?

De Selby had closed the safe and press door and gone back to his seat.

– Just a whim of mine, no more, he replied. The letters are in no sense a formula or even a mnemonic. But that container has in it the most priceless substance on earth.

– Mr De Selby, Mick said, rather frightened by these flamboyant proceedings, granted that your safe is a good one, is it not foolish to leave such dangerous stuff here for some burglar to knock it off?

– Me, for instance? Hackett interposed.

– No, gentlemen, there is no danger at all. Nobody would know what the substance was, its properties or how activated.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.