Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «This Fight is Our Fight: The Battle to Save Working People»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

First published in the United States by Henry Holt and Company in 2017

Copyright © Elizabeth Warren 2017

Afterword copyright © Elizabeth Warren 2018

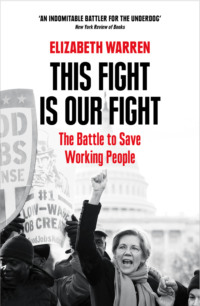

Cover photograph by Alex Wong / Staff / Getty Images

Elizabeth Warren assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008254575

Ebook Edition © 2018 ISBN: 9780008254544

Version: 2018-05-12

Praise for Elizabeth Warren:

‘This Fight Is Our Fight is a smart, tough-minded book … What Democrats need right now is a reason to keep fighting. And that’s something Warren’s muscular, unapologetic book definitely offers. It’s an important contribution’

New York Times

‘This Fight Is Our Fight provides an insider’s look at the machinations that are undermining the US economy and political system. Warren spells out what is happening and what needs to be done to reverse the slide … It is unusual for any politician to be so open’

New York Journal of Books

‘Girded for battle, the senior senator from Massachusetts forcefully lays out the bleak picture of an American government increasingly controlled by corporate greed and special interests … The author sounds the alarm that an oligarchy is in the making, and her urgency is palpable and necessary. Inspiring words to empower Warren’s marching army’

Kirkus, starred review

‘Warren’s moment has arrived … To understand why Senator Elizabeth Warren is the fastest-rising new star in the Democratic Party … read her new book’

The Hill

‘A startling account of the elusiveness of the American Dream’

TIME

‘She is still the fiery advocate who called for a bureau to protect consumers’

New York Times

‘After reading this book, it is comforting to know that Elizabeth Warren, with her passion, anger and bluntness, will not be silenced’

Washington Post

‘Intelligent and informative … [Warren is] good, plainspoken company who makes you feel smarter for having spent such easy time with her’

Entertainment Weekly

‘As a politician and activist, Warren’s great strength is that she retains the outsider’s perspective, and the outsider’s sense of moral outrage … she doesn’t take no for an answer’

New York Review of Books

‘The Wall Street watchdog and US senator has produced a readable and sometimes infuriating explanation of the biggest financial crisis of our time’

People

‘[Warren] has a compelling story to tell … She is also entertaining about professional politics’

Economist

‘Revealing … Warren’s book describes the troubling patterns and practices of high-level Washington’

GRETCHEN MORGENSON, New York Times

‘Warren has written a good book … Frank and quite strong’

The Nation

‘[A] call to arms … you can hear the sound of the crowd roaring with approval’

Mother Jones

‘[Warren] displays a down-home charm and an effortless rapport with everyday people … Warren emerges as a committed advocate with real world sensibility, who tasted tough economic times at an early age and did not forget its bitterness’

Publishers Weekly, starred review

Dedication

To the people of Massachusetts, who sent me into this fight

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Elizabeth Warren

Dedication

Prologue

1. The Disappearing Middle Class

2. A Safer Economy

3. Making—and Breaking—the Middle Class

4. The Rich and Powerful Tighten Their Grip

5. The Moment of Upheaval

Epilogue

Afterword to the 2018 Edition

Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Elizabeth Warren

About the Publisher

Prologue

“I’ll get the popcorn.”

I yelled up the stairs to let Bruce know I was coming. I also had the beer and my laptop.

He had the television on, with the second season of Ballers lined up. Our son had hooked us on it the year before, and we’d been saving the shows until tonight—Election Night.

It was November 8, 2016. The polls were about to close in Massachusetts, and we were about to start our Election Night ritual: clicking back and forth between news reports and binge-watching something really fun on television. I had my laptop so I could check on the local races, and my phone so, assuming the night went well, I could make some congratulatory calls.

Yeah, until I won my Senate race in 2012 I’d have guessed that a senator would watch election returns like a pro: a big group of people in a war room somewhere, multiple television screens on the walls, phones ringing, people rushing in with last-minute information. Lots of coffee cups and pizza boxes strewn over desks. Someone making pithy remarks about what it means that with 2 percent of Illinois reporting, Duckworth has a four-point lead, and turnout in the Seventh Precinct is high, and so on. In fact, I think I’ve seen that scene in the movies.

But not Bruce and me, not tonight. I wasn’t on the ballot this year, so I wouldn’t be huddling with a campaign team. Besides, by this point, there wasn’t anything else I could do to affect the election’s outcome. And with so much on the line, I knew that watching the numbers drift in over the next few hours would be agony.

For so many of these races, I’d been out there with the candidates—cheered them on, given speeches standing next to them, frozen and sweated and stepped in muck right along with them. Hillary Clinton’s race, of course, was the night’s biggest, but I would be chewing my fingernails watching the Senate races as well. There was Catherine Cortez Masto, a former attorney general in Nevada whom I’d worked with while fighting the banks during the housing crisis eight years ago. Katie McGinty, a former environmental policy official in Pennsylvania who was trying to unseat a Republican who seemed to be funded by an endless supply of Wall Street money. Russ Feingold, the former senator from Wisconsin who had been in the trenches with me as we’d fought to save families from predatory lenders fifteen years earlier and was making a strong push to get his old seat back. Maggie Hassan, the governor from just across the border in New Hampshire, where I had gone time after time to help out. Jason Kander, a progressive Democrat in Missouri who was running uphill hard. Tammy Duckworth, a vet in Illinois who had lost both legs in Iraq and, no surprise, turned out to be a fierce campaigner. Kamala Harris, the California AG I’d gone into battle with shoulder to shoulder many times. And so many more. For months, these candidates had put it all on the line. Faces, names, stories—they all crowded in that night, and I was anxious and hopeful and fearful for every one of them.

No, I didn’t want to watch the numbers trickle in with a big group. I just wanted to be at home with Bruce. That night we did what we always did—toggled back and forth between a television show and the election results. Sitting on the couch eating popcorn, drinking beer, and hoping for the best.

Ballers was terrific. The 2016 election, not so much.

The first sign of trouble was how quickly several Senate races were called for Republicans. Indiana. Florida. Suddenly candidates we thought would win were struggling—Russ in Wisconsin and Katie in Pennsylvania. And then it looked like Hillary was in trouble, too.

It was like watching a train wreck in slow motion. One car hurtled off the tracks, then another crumpled, then fires and explosions and bodies flying everywhere.

As I watched the White House slip away and the Democratic losses mount, I knew that a lot of people would spend weeks analyzing what had gone wrong, how this moment had come to pass. There would be lots of pundits. (“I always knew …”) Lots of partisans. (“Of course this loss happened because they …”) Lots of political types certain that they could have done it all much, much better.

Sure, there would be endless autopsies of the 2016 campaigns, but as that long night wore on, I found myself thinking less about the political winds and more about how the fallout from this election would deliver one more body blow to so many working families. The television showed crowds of candidates and supporters celebrating or grieving, but what haunted me was the thought that for tens of millions of Americans, life was about to get a whole lot tougher.

LONG BEFORE I ever came within a hundred miles of politics, I had been a teacher and a researcher. I had spent years tracking what was happening to America’s middle class, what was happening to working families and families that wanted to be working families. It was a great and terrible story.

The tale of America coming out of the Great Depression and not only surviving but actually transforming itself into an economic giant is the stuff of legend. But the part that gives me goose bumps is what we did with all that wealth: over several generations, our country built the greatest middle class the world had ever known.

We built it ourselves, using our own hard work and the tools of government to open up more opportunities for millions of people. We used it all—tax policy, investments in public education, new infrastructure, support for research, rules that protected consumers and investors, antitrust laws—to promote and expand our middle class. The spectacular, shoot-off-the-fireworks fact is that we succeeded. Income growth was widespread, and the people who did most of the work—the 90 percent of America—also got most of the gains. In the 1960s and 1970s, I was one of the lucky beneficiaries of everything America was building, and to this day, I am grateful to the bottom of my soul.

But now, in a new century and a different time, that great middle class is on the ropes. All across the country, people are worried—worried and angry.

They are angry because they bust their tails and their income barely budges. Angry because their budget is stretched to the breaking point by housing and health care. Angry because the cost of sending their kid to day care or college is out of sight.

People are angry because trade deals seem to be building jobs and opportunities for workers in other parts of the world, while leaving abandoned factories here at home. Angry because young people are getting destroyed by student loans, working people are deep in debt, and seniors can’t make their Social Security checks cover their basic living expenses. Angry because we can’t even count on the fundamentals—roads, bridges, safe water, reliable power—from our government. Angry because we’re afraid that our children’s chances for a better life won’t be as good as our own.

People are angry, and they are right to be angry. Because this hard-won, ruggedly built, infinitely precious democracy of ours has been hijacked.

Today this country works great for those at the top. It works great for every corporation rich enough to hire an army of lobbyists and lawyers. It works great for every billionaire who pays taxes at lower rates than the hired help. It works great for everyone with the money to buy favors in Washington. Government works great for them, but for everyone else, this country is no longer working very well.

This is the most dangerous kind of corruption. No, it’s not old-school bribery with envelopes full of cash. This much smoother, slicker, and better-dressed form of corruption is perverting our government and making sure that day after day, decision after decision, the rich and powerful are always taken care of. This corruption is turning government into a tool of those who have already gathered wealth and influence. This corruption is hollowing out America’s middle class and tearing down our democracy.

In 2016, into this tangle of worry and anger, came a showman who made big promises. A man who swore he would drain the swamp, then surrounded himself with the lobbyists and billionaires who run the swamp and feed off government favors. A man who talked the talk of populism but offered the very worst of trickle-down economics. A man who said he knew how the corrupt system worked because he had worked it for himself many times. A man who vowed to make America great again and followed up with attacks on immigrants, minorities, and women. A man who was always on the hunt for his next big con.

In the months ahead, it would become clear that this man was even more divisive and dishonest than his presidential campaign revealed. But on election night, I stared at the television as it sank in that this man was about to become the next president of the United States.

The election results kept rolling in, and I knew that plenty of people would be eager to describe the special appeal of Donald Trump and explain all the reasons why he won. But we need more than an explanation of just one election; we also need to understand how and why our country has gone so thoroughly wrong. We need a plan to put us back on track—and then we need to get to work and make it happen.

We need to live our values, to be the kind of nation that invests in opportunity, not just for some of us, but for all of us. We need to take our democracy back from those who would pervert it for their own benefit. We need to build the America of our best dreams.

Sitting on the couch with Bruce, I watched Donald Trump say that his presidency would be “a beautiful thing.” No, I thought, it won’t be anything like beautiful. Worse, the man who would soon move into the White House had the capacity to bear down on a middle class that was already on the ropes and deliver the knockout punch.

If ever there was a time to fight, this was it.

1

The Disappearing Middle Class

I was ready to go.

It was a Thursday morning in March 2013. I’d been in the Senate for two and a half months, and this was our first hearing on the minimum wage. For close to four years, the federal minimum wage had been frozen at $7.25 an hour. The rate was already low by historic standards, and a lot of workers were sinking. Minimum wage is just that—the minimum.

When I am home in Massachusetts, I make a point of speaking with as many Bay Staters as I can. This includes the people who do the service work in big buildings. These are the workers who stock the office kitchens, keep the buildings clean, provide security. I’ve been struck by how many of them hold down two or three jobs just to stay afloat. Women who take the T into Boston, work a full shift cleaning buildings, then stay to work a morning shift at one of the counters at South Station. Men who push wheelchairs and haul bags at Logan Airport all day, then drive cabs or work security in the evening. And I meet them outside Boston too. Mothers and fathers in New Bedford and Fall River, in Worcester and Springfield, who work at fast-food places in town or on the highway, piecing together a living from whatever jobs they can find. A woman up on the North Shore told me she sleeps in her car in the parking lot in the hours between when one job ends and the other begins. She said she’s so tired that when she drives to her mother’s house to pick up her baby daughter, she falls asleep on the couch the minute she gets there. Low-wage workers—in Massachusetts and in all the other states too—are among the hardest working people in America.

I’m pretty hard-core about this issue. The way I see it, no one in this country should work full-time and still live in poverty—period. But at $7.25 an hour, a mom working a forty-hour-a-week minimum-wage job cannot keep herself and her baby above the poverty line. This is wrong—and this was something the U.S. Congress could make better if we’d just raise the minimum wage. We could fix this now.

Ten weeks on the job, and it still gave me a thrill to walk into the Senate hearing rooms, notebook tucked under my arm. This room was like a stage set: high ceilings, heavy paneling, and dark blue carpets. The lights were mounted on the walls, giant art deco torches that looked like they were illuminating an ancient temple. The room was so vast that everyone had to use microphones just to hear each other.

Senators were seated on a raised platform, assigned places around a giant, wood-paneled horseshoe-shaped dais. Our chairs were huge, high-backed leather affairs, sort of ancient king meets modern CEO. Witnesses sat at a low table in the open part of the U, with the audience behind them. The room’s design is intended to evoke the grandeur and solemnity of the Senate, a not-very-subtle reminder of the power of this body.

In keeping with the Senate’s rigid deference to seniority and my junior status, my chair was the farthest from center stage, out on one end of the horseshoe. I didn’t care. I was aware that this was pretty routine stuff for most senators. And okay, I understood that this committee wasn’t going to do a movie moment and suddenly jump up and demand in the name of working people everywhere that Congress increase the minimum wage.

I knew that, but I also knew that the move to raise the minimum wage was gaining traction around the country. And I knew that this hearing was a pretty good platform to move that fight forward. After all, this committee really did have the power to recommend a raise for thirty million Americans, and even if we weren’t going to do it today, I wanted to make sure we made some progress. If you don’t fight, you can’t win.

Committee hearing on the minimum wage. That’s me at the far right end of the horseshoe.

I also understood that for more than forty years, workers’ pay hadn’t kept pace with inflation. Productivity had gone up. Profits had gone up. Executives had gotten raises. Couldn’t we at last come together to make sure that the people who did some of the hardest, dirtiest work in the nation got at least a chance to build a little security?

And couldn’t we also give this whole “bipartisan” thing another try? Since the 1930s, Republicans had joined Democrats to support periodic increases to the minimum wage, and now, after four years of holding steady, I thought we might come together for some kind of increase. Okay, it probably wouldn’t be as much as I wanted, but couldn’t we at least do something?

No. The Republicans were locked in: they would block any efforts to increase the minimum wage by even a few nickels.

The hearing produced some sharp back-and-forth about the impact that raising the minimum wage might have on jobs. The data are clear: study after study shows that there are no large adverse effects on jobs when the minimum wage goes up—and one of the country’s leading experts was sitting right in front of us testifying to exactly that point. I battled a couple of the other witnesses, and I got in my licks about how far the real minimum wage had fallen, but after about an hour and a half, the hearing began winding down.

I gathered up my papers, ready to leave as soon as the gavel fell. Lamar Alexander, the senator from Tennessee and the most senior Republican on the committee, was asking his last questions when a witness interrupted him to point out that Congress was responsible for setting the right level for the minimum wage.

Senator Alexander replied that if he could decide, there would be no minimum.

No minimum wage at all. Not $15.00. Not $10.00. Not $7.25. Not $5.00. Not $1.00.

The comment was delivered quite casually. It wasn’t a grand pronouncement shouted by a crazy, hair-on-fire ideologue. Instead, a longtime U.S. senator stated with calm confidence that if an employer could find someone desperate enough to take a job for fifty cents an hour, then that employer should have the right to pay that wage and not a penny more. He might as well have said that employers could eat cake and the workers could scramble for whatever crumbs fall off the table.

For just a blink, I wasn’t in a heavily paneled Senate hearing room. I wasn’t sitting at an elevated dais. I didn’t have an aide seated behind me and cameras pointed my way.

FOR JUST A blink, I was a skinny sixteen-year-old girl, back in Oklahoma City. It was early in the fall, and I had just started my senior year of high school.

By then we were a small family: all that was left of us was Mother, Daddy, and me. My three older brothers had each in turn left for the military, gotten married, and were starting families of their own.

Like every family, we’d had our ups and downs, but from my teenage perspective, life felt a little steadier again. Mother answered phones at Sears, and Daddy sold lawn mowers and fences. Two paychecks. It had been a couple of years since the bill collectors had called or people had threatened to take away our home. Late at night, I no longer heard the muffled sounds of my mother crying.

But it was still tough. There was no extra money, no breathing room. I waited tables and babysat. I picked up a few dollars sewing and ironing, although nothing regular. I was sixteen—sixteen and watching the world slip away. This was my last year of high school, and it looked like everyone at Northwest Classen had a future, everyone except me. All my friends were talking about college. They went on nonstop as they compared schools and sororities and possible majors. No one seemed to worry about what it would cost. Me? I didn’t have the money for a college application, much less tuition and books. Some days it seemed like college might as well have been on the moon.

It was a miserable time in my life.

One night my mother and I had another fight about what I should do after high school. I look back now and realize that she was trying her best. She worked long hours, and she sometimes seemed stretched to the breaking point.

On this one night, it all spun out of control. She had been yelling at me. Why was I so special that I had to go to college? Did I think I was better than everyone else in the family? Where would the money come from? I did the usual: I stared at the floor in silence, and when I’d had enough, I retreated to my bedroom. But this time, retreat wasn’t enough. She followed me into my room and kept yelling. I finally jumped up from my desk and screamed at her to leave me alone.

Quick as lightning, she hit me hard in the face.

I think we were both stunned. She backed out of my room. I stuffed a handful of clothes into a canvas bag and raced out the front door.

Hours later, Daddy found me downtown, sitting on a bench at the bus station. My face was red, and I was still shaking. I was hurt—hurt and discouraged.

Everything in my life seemed wrong.

Daddy sat down beside me on the bench, and for a long time he said nothing. Both of us stared ahead. After a while, he asked if I was hungry. He walked over to a vending machine and brought back some cracker sandwiches. Then he asked me if I remembered the time after his heart attack, those hard months when he and Mother were sure they were about to lose the house.

I remembered.

It had been nearly four years earlier. After his heart attack, Daddy had been in the hospital for a long time, and when he came home he was gray and even quieter than usual. He spent hours sitting alone, smoking cigarettes and looking off into space. He moved into the tiny bedroom that had been left empty when my brother David joined the army.

For months, my mother carried around Kleenex or the cheap off-brand she usually bought. She worked the tissues into shreds, leaving them balled up in ashtrays and on her dresser. But she always had one ready in case she started to cry. And she cried a lot.

Daddy said it was the worst time in his life. Worse than when the doctors thought the lumps on his neck were cancer. Worse than when his best friend, Claude, died. Worse than when he was in a terrible car crash and smashed through the windshield and tore his shoulder open.

“Your mother was at home when they took the station wagon,” he said, his voice low. “And then they said they were going to take the house. She cried every night.”

He paused for a long time. “I just couldn’t face it.”

Sitting there on the bench in the bus station, he told me that he had failed and that the shame had nearly killed him. He wanted to die. He wanted to disappear from our lives and from the earth and from everything that had gone wrong. He would think about how bad things were and ask whether this was the night to leave my mother and me.

What happened? I asked.

Daddy sat silently for a long time, caught somewhere in his memories of those awful days. He still didn’t look at me. Finally, he took my hand in both of his and held it tightly.

It got better, he said. Your mother found work. We made some payments. After a while, I went back to work. We had less money, but it was enough to get by. We got caught up on the mortgage. You seemed to do okay.

Finally he turned and looked at me. “Life gets better, punkin.”

My daddy said, “Life gets better, punkin.”

And that’s how I’d always remembered this moment: my daddy telling me to hang on, that no matter how bad it feels, life gets better. I had carried that story in my pocket for decades. It was how I made it through the painful parts. Divorce. Disappointments. Deaths. Whenever things got really tough, I would pull out that story and hold it in my mind. I’d hear my daddy’s voice, and I’d always feel better. By now, his line was a part of me.

Life gets better, punkin.

IT WAS JUST a blink before I was back in that fancy hearing room again. But that’s all it takes—just a blink—to change someone’s life. My daddy’s life. My mother’s life. My life.

As I walked back to my office, I thought about how close my family had come to disaster. After my daddy’s heart attack, we were tumbling down a hill toward a cliff, and we had been just about to go over the edge when my mother grabbed a branch—a job at Sears. She was fifty years old, and for the first time in her life she had a job with a paycheck. She answered phones and took catalog orders. In a cramped room with no windows, eight women, mostly hard-pressed mothers like her, sat all day long, ready to help customers who called. She wore high heels and hose, and every day she and her coworkers took forty minutes for lunch and two breaks that lasted exactly ten minutes each.

And she was paid minimum wage.

So when Senator Alexander said there would be no minimum wage if it were up to him, I thought about how much that job had meant to Mother and Daddy and me. My mother’s minimum-wage job not only saved our house—it saved our family. No, it didn’t make our lives perfect. It took years to work off the medical bills from my father’s heart attack. My mother worked and reworked her grocery list to squeeze out every last nickel. The carpet in the living room got worn through to the bare floor. And there were times when my mother’s anxieties took over and she lashed out, and times when my daddy got scary quiet. But we hung together. We made it—shaken, but still standing.

What if Mother hadn’t earned enough money to keep us going after Daddy got sick? We’d already lost the family station wagon. What if we’d lost the house? What would the shame have done to my daddy? And if he had left us forever? What would the loss have done to Mother and me? Would I have ever made it to college? Or would she and I have clung to each other, both so fatally wounded that neither of us could ever have recovered?

I don’t know what would have happened if Mother hadn’t been able to break our fall with a minimum-wage job at Sears. But I do know that policy decisions about important issues like the minimum wage matter. Those decisions—made in far-off Washington, reached in elegant rooms by confident, well-fed men and women—really matter.

Back in the 1960s, when my mother worked at Sears, a minimum-wage job could keep a family of three afloat. Mother had a high school education and no work experience, but when Sears needed someone to answer the phones, the law required the company to pay her an hourly rate that was enough to keep our family of three up and on our feet.

And that’s where the sick-in-the-back-of-the-throat unfairness of it nearly chokes me. In the years since my mother went to work at Sears, America has gotten richer. In fact, the country’s total wealth is at an all-time high.