Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Code Name Verity»

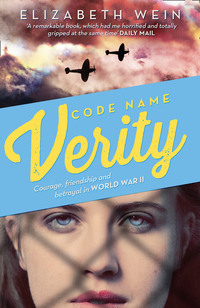

PRAISE FOR

CODE NAME VERITY

‘Code Name Verity does more than stick with me. It haunts me. I just can’t recommend it enough’

Author Maggie Stiefvater

‘I liked Code Name Verity enormously . . . you are sucked into the viewpoint and don’t realise for a long time that everything is double edged and has a second meaning’

Author Helen Dunmore

‘A fiendishly plotted mind game of a novel, the kind you have to read twice’

Majorie Ingalls, New York Times

‘An utterly compelling, gripping novel that parachutes you into a vividly real world, and challenges everything you think you know. I found it impossible to put down’

Author Rowan Coleman

Also by Elizabeth Wein

ROSE UNDER FIRE

A special edition of Elizabeth Wein’s award-winning novel, including exclusive videos of the author on location at The Shuttleworth Collection, a peep into her personal collection of memorabilia and the short story that began it all, never previously published in the UK.

Features

Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein

An Interview with Elizabeth Wein

Something Worth Doing

The Shuttleworth Videos:

‘Fly the Plane, Maddie’

The ATA

SOE Agent Odette Hallowes

Anti-aircraft Gun

Tiger Moth

‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’

The Verity Collection

Preview – Rose Under Fire

For Amanda

—we make a sensational team—

‘Passive resisters must understand that they are as important as saboteurs.’

SOE Secret Operations Manual,

‘Methods of Passive Resistance’

Part 1

Ormaie 8.XI.43 JB-S

I AM A COWARD

I wanted to be heroic and I pretended I was. I have always been good at pretending. I spent the first twelve years of my life playing at the Battle of Stirling Bridge with my five big brothers, and even though I am a girl they let me be William Wallace, who is supposed to be one of our ancestors, because I did the most rousing battle speeches. God, I tried hard last week. My God, I tried. But now I know I am a coward. After the ridiculous deal I made with SS-Hauptsturmführer von Linden, I know I am a coward. And I’m going to give you anything you ask, everything I can remember. Absolutely Every Last Detail.

Here is the deal we made. I’m putting it down to keep it straight in my own mind. ‘Let’s try this,’ the Hauptsturmführer said to me. ‘How could you be bribed?’ And I said I wanted my clothes back.

It seems petty, now. I am sure he was expecting my answer to be something defiant – ‘Give me Freedom’ or ‘Victory’ – or something generous, like ‘Stop toying with that wretched French Resistance laddie and give him a dignified and merciful death.’ Or at least something more directly connected to my present circumstance, like ‘Please let me go to sleep’ or ‘Feed me’ or ‘Get rid of this sodding iron rail you have kept tied against my spine for the past three days.’ But I was prepared to go sleepless and starving and upright for a good while yet if only I didn’t have to do it in my underwear – rather foul and damp at times, and SO EMBARRASSING. The warmth and dignity of my flannel skirt and woolly jumper are worth far more to me now than patriotism or integrity.

So von Linden sold my clothes back to me piece by piece. Except my scarf and stockings of course, which were taken away early on to prevent me strangling myself with them (I did try). The pullover cost me four sets of wireless code – the full lot of encoding poems, passwords and frequencies. Von Linden let me have the pullover back on credit straight away. It was waiting for me in my cell when they finally untied me at the end of that dreadful three days, though I was incapable of getting the damned thing on at first; but even just dragged over the top of me like a shawl it was comforting. Now that I’ve managed to get into it at last I don’t think I shall ever take it off again. The skirt and blouse cost rather less than the pullover, and it was only one code set apiece for my shoes.

There are eleven sets in all. The last one was supposed to buy my slip. Notice how he’s worked it that I get the clothes from the outside in, so I have to go through the torment of undressing in front of everybody every time another item is given back to me. He’s the only one who doesn’t watch – he threatened to take it all away from me again when I suggested he was missing a fabulous show. It was the first time the accumulated damage has really been on display and I wish he would have looked at his masterpiece – at my arms particularly – also the first time I have been able to stand in a while, which I wanted to show off to him. Anyway I have decided to do without my slip, which also saves me the trouble of stripping again to put it on, and in exchange for the last code set I have bought myself a supply of ink and paper – and some time.

Von Linden has said I have got two weeks and that I can have as much paper as I need. All I have to do is cough up everything I can remember about the British War Effort. And I’m going to. Von Linden resembles Captain Hook in that he is rather an upright sort of gentleman in spite of his being a brute, and I am quite Pan-like in my naïve confidence that he will play by the rules and keep his word. So far he has. To start off my confession, he has given me this lovely creamy embossed stationery from the Château de Bordeaux, the Bordeaux Castle Hotel, which is what this building used to be. (I would not have believed a French hotel could become so forbiddingly bleak if I had not seen the barred shutters and padlocked doors with my own eyes. But you have also managed to make the whole beautiful city of Ormaie look bleak.)

It is rather a lot to be resting on a single code set, but in addition to my treasonous account I have also promised von Linden my soul, although I do not think he takes this seriously. Anyway it will be a relief to write anything that isn’t connected with code. I’m so dreadfully sick of spewing wireless code. Only when we’d put all those lists to paper did I realise what a huge supply of code I do actually have in me.

It’s jolly astonishing really.

YOU STUPID NAZI BASTARDS.

I’m just damned. I am utterly and completely damned. You’ll shoot me at the end no matter what I do, because that’s what you do to enemy agents. It’s what we do to enemy agents. After I write this confession, if you don’t shoot me and I ever make it home, I’ll be tried and shot as a collaborator anyway. But I look at all the dark and twisted roads ahead and this is the easy one, the obvious one. What’s in my future – a tin of kerosene poured down my throat and a match held to my lips? Scalpel and acid, like the Resistance boy who won’t talk? My living skeleton packed up in a cattle wagon with two hundred desperate others, carted off God knows where to die of thirst before we get there? No. I’m not travelling those roads. This is the easiest. The others are too frightening even to look down.

I am going to write in English. I don’t have the vocabulary for a warfare account in French, and I can’t write fluently enough in German. Someone will have to translate for Hauptsturmführer von Linden; Fräulein Engel can do it. She speaks English very well. She is the one who explained to me that paraffin and kerosene are the same thing. We call it paraffin at home, but the Americans call it kerosene, and that is more or less what the word sounds like in French and German too.

(About the paraffin, kerosene, whatever it is. I do not really believe you have a litre of kerosene to waste on me. Or do you get it on the black market? How do you claim the expense? ‘1 lt. highly explosive fuel for execution of British spy.’ Anyway I will do my best to spare you the expense.)

One of the first items on the very long list I have been given to think about including in my confession is Location of British Airfields for Invasion of Europe. Fräulein Engel will confirm that I burst out laughing when I read that. You really think I know a damned thing about where the Allies are planning to launch their invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe? I am in the Special Operations Executive because I can speak French and German and am good at making up stories, and I am a prisoner in the Ormaie Gestapo HQ because I have no sense of direction whatsoever. Bearing in mind that the people who trained me encouraged my blissful ignorance of airfields just so I couldn’t tell you such a thing if you did catch me, and not forgetting that I wasn’t even told the name of the airfield we took off from when I came here, let me remind you that I had been in France less than 48 hours before that obliging agent of yours had to stop me being run over by a French van full of French chickens because I’d looked the wrong way before crossing the street. Which shows how cunning the Gestapo are. ‘This person I’ve pulled from beneath the wheels of certain death was expecting traffic to travel on the left side of the road. Therefore she must be British, and is likely to have parachuted into Nazi-occupied France out of an Allied plane. I shall now arrest her as a spy.’

So, I have no sense of direction; in some of us it is a TRAGIC FLAW, and there is no point in me trying to direct you to Locations of Any Airfields Anywhere. Not without someone giving me the coordinates. I could make them up, perhaps, and be convincing about it, to buy myself more time, but you would catch on eventually.

Aircraft Types in Operational Use is also on this list of things I am to tell you. God, this is a funny list. If I knew or cared a damned thing about aircraft types I would be flying planes for the Air Transport Auxiliary like Maddie, the pilot who dropped me here, or working as a fitter, or a mechanic. Not cravenly coughing up facts and figures for the Gestapo. (I will not mention my cowardice again because it is beginning to make me feel indecent. Also I do not want you to get bored and take this handsome paper away and go back to holding my face in a basin of ice water until I pass out.)

No, wait, I do know some aircraft types. I will tell you all the aircraft types I know, starting with the Puss Moth. That was the first aircraft my friend Maddie ever flew. In fact it was the first aircraft she ever had a ride in, and even the first one she ever got close to. And the story of how I came to be here starts with Maddie. I don’t think I’ll ever know how I ended up carrying her National Registration card and pilot’s licence instead of my own ID when you picked me up, but if I tell you about Maddie you’ll understand why we flew here together.

Aircraft Types

Maddie is properly Margaret Brodatt. You have her ID, you know her name. Brodatt is not a Northern English name, it is a Russian name, I think, because her grandfather came from Russia. But Maddie is pure Stockport. Unlike me, she has an excellent sense of direction. She can navigate by the stars, and by dead reckoning, but I think she learned to use her sense of direction properly because her granddad gave her a motorbike for her sixteenth birthday. That was Maddie away out of Stockport and up the unmade lanes on the high moors of the Pennine hills. You can see the Pennines all around the city of Stockport, green and bare with fast-moving stripes of cloud and sunlight gliding overhead like a Technicolor moving picture. I know because I went on leave for a weekend and stayed with Maddie and her grandparents, and she took me on her motorbike up the Dark Peak, one of the most wonderful afternoons of my life. It was winter and the sun came out only for about five minutes and even then the sleet didn’t stop falling – it was because the weather was forecast so unflyable that she had the three days off. But for five minutes Cheshire seemed green and sparkling. Maddie’s granddad owns a bike shop and he got some black market petrol for her specially when I visited. I am putting this down (even though it’s nothing to do with Aircraft Types) because it proves that I know what I’m talking about when I describe what it was like for Maddie to be alone at the top of the world, deafened by the roar of four winds and two cylinders, with all the Cheshire plain and its green fields and red chimneys thrown at her feet like a tartan picnic blanket.

Maddie had a friend called Beryl who had left school, and in the summer of 1938 Beryl was working in the cotton mill at Ladderal, and they liked to take Sunday picnics on Maddie’s motorbike because it was the only time they saw each other any more. Beryl rode with her arms tight round Maddie’s waist, like I did that time. No goggles for Beryl, or for me, though Maddie had her own. On this particular June Sunday they rode up through the lanes between the drystone walls that Beryl’s labouring ancestors had built, and over the top of Highdown Rise, with mud up their bare shins. Beryl’s best skirt was ruined that day and her dad made her pay for a new one out of her next week’s wages.

‘I love your granddad,’ Beryl shouted in Maddie’s ear. ‘I wish he was mine.’ (I wished that too.) ‘Fancy him giving you a Silent Superb for your birthday!’

‘It’s not so silent,’ Maddie shouted back over her shoulder. ‘It wasn’t new when I got it, and it’s five years old now. I’ve had to rebuild the engine this year.’

‘Won’t your granddad do it for you?’

‘He wouldn’t even give it to me until I’d taken the engine apart. I have to do it myself or I can’t have it.’

‘I still love him,’ Beryl shouted.

They tore along the high green lanes of Highdown Rise, along tractor ruts that nearly bounced them over drystone field walls and into a bed of mire and nettles and sheep. I remember and I know what it must have been like. Every now and then, round a corner or at the crest of a hump in the hill, you can see the bare green chain of the Pennines stretching serenely to the west, or the factory chimneys of South Manchester scrawling the blue north sky with black smoke.

‘And you’ll have a skill,’ Beryl yelled.

‘A what?’

‘A skill.’

‘Fixing engines!’ Maddie howled.

‘It’s a skill. Better than loading shuttles.’

‘You’re getting paid for loading shuttles,’ Maddie yelled back. ‘I don’t get paid.’ The lane ahead was rutted with rain-filled potholes. It looked like a miniature landscape of Highland lochs. Maddie slowed the bike to a putter and finally had to stop. She put her feet down on solid earth, her skirt rucked up to her thighs, still feeling the Superb’s reliable and familiar rumble all through her body. ‘Who’ll give a girl a job fixing engines?’ Maddie said. ‘Gran wants me to learn to type. At least you’re earning.’

They had to get off the bike to walk it along the ditch-filled lane. Then there was another rise, and they came to a farm gate set between field boundaries, and Maddie leaned the motorbike against the stone wall so they could eat their sandwiches. They looked at each other and laughed at the mud.

‘What’ll your dad say!’ Maddie exclaimed.

‘What’ll your gran!’

‘She’s used to it.’

Beryl’s word for picnic was ‘baggin’, Maddie said, doorstep slices of granary loaf Beryl’s auntie baked for three families every Wednesday, and pickled onions as big as apples. Maddie’s sandwiches were on rye bread from the baker’s in Reddyke where her grandmother sent her every Friday. The pickled onions stopped Maddie and Beryl having a conversation because chewing made so much crunching in their heads they couldn’t hear each other talk, and they had to be careful swallowing so they wouldn’t be asphyxiated by an accidental blast of vinegar. (Perhaps Chief-Storm-Captain von Linden might find pickled onions useful as persuasive tools. And your prisoners would get fed at the same time.)

(Fräulein Engel instructs me to put down here, for Captain von Linden to know when he reads it, that I have wasted 20 minutes of the time given me because here in my story I laughed at my own stupid joke about the pickled onions and broke the pencil point. We had to wait for someone to bring a knife to sharpen it because Miss Engel is not allowed to leave me by myself. And then I wasted another 5 minutes weeping after I snapped off the new point straight away because Miss E. had sharpened it very close to my face, flicking the shavings into my eyes while SS-Scharführer Thibaut held my head still, and it made me terribly nervous. I am not laughing or crying now and will try not to press so hard after this.)

At any rate, think of Maddie before the war, free and at home with her mouth full of pickled onion – she could only point and choke when a spluttering, smoking aircraft hove into view above their heads and circled the field they were overlooking as they perched on the gate. That aircraft was a Puss Moth.

I can tell you a bit about Puss Moths. They are fast, light monoplanes – you know, only one set of wings – the Tiger Moth is a biplane and has two sets (another type I have just remembered). You can fold the Puss Moth’s wings back for trucking the machine around or storing it, and it has a super view from the cockpit, and can seat two passengers as well as the pilot. I have been a passenger in one a couple of times. I think the upgraded version is called a Leopard Moth (that’s three aircraft I have named in one paragraph!).

This Puss Moth circling the field at Highdown Rise, the first Puss Moth Maddie ever came across, was choking to death. Maddie said it was like having a ringside seat at the circus. With the plane at three hundred feet she and Beryl could see every detail of the machine in miniature: every wire, every strut of its pair of canvas wings, the flicker of the wooden propeller blades as they spun ineffectively in the wind. Great blue clouds of smoke billowed from the exhaust.

‘He’s on fire!’ screamed Beryl in a fit of delighted panic.

‘He’s not on fire. He’s burning oil,’ Maddie said because she knows these things. ‘If he has any sense he’ll shut everything off and it’ll stop. Then he can glide down.’

They watched. Maddie’s prediction came true: the engine stopped and the smoke drifted away, and now the pilot was clearly planning to put his damaged rig down in the field right in front of them. It was a grazing field, unploughed, unmown, without any livestock in it. The wings above their heads cut out the sun for a second with the sweep and billow of a sailing yacht. The aircraft’s final pass pulled all the litter of their lunch out into the field, brown crusts and brown paper fluttering in the blue smoke like the devil’s confetti.

Maddie says it would have been a good landing if it had been on an aerodrome. In the field the wounded flying machine bounced haplessly over the unmown grass for thirty yards. Then it tipped up gracefully on to its nose.

Unthinkingly, Maddie broke into applause. Beryl grabbed her hands and smacked one of them.

‘You gormless cow! He might be hurt! Oh, what shall we do!’

Maddie hadn’t meant to clap. She had done it without thinking. I can picture her, blowing the curling black hair out of her eyes, with her lower lip jutting out before she jumped down from the gate and hopped over the green tussocks to the downed plane.

There were no flames. Maddie scaled her way up the Puss Moth’s nose to get at the cockpit and put one of her hobnailed shoes through the fabric that covered the fuselage (I think that’s what the body of the plane is called) and I bet she cringed; she hadn’t meant to do that either. She was feeling very hot and bothered by the time she unlatched the door, expecting a lecture from the aircraft’s owner, and was shamefully relieved to find the pilot hanging upside-down in half-undone harness straps and clearly stone-cold unconscious. Maddie glanced over the alien engine controls. No oil pressure (she told me all this). Throttle, out. Off. Good enough. Maddie untangled the harness and let the pilot slither to the ground.

Beryl was there to catch the dragging weight of the pilot’s senseless body. It was easier for Maddie to get down off the plane than it had been for her to get up, just a light hop to the ground. Maddie unbuckled the pilot’s helmet and goggles; she and Beryl had both done First Aid in Girl Guides, for all that’s worth, and knew enough to make sure the casualty could breathe.

Beryl began to giggle.

‘Who’s the gormless cow!’ Maddie exclaimed.

‘It’s a girl!’ Beryl laughed. ‘It’s a girl!’

—

Beryl stayed with the unconscious girl pilot while Maddie rode her Silent Superb to the farm to get help. She found two big strong lads her own age shovelling cow dung, and the farmer’s wife sorting First Early potatoes and cursing a cotillion of girls who were doing a huge jigsaw on the old stone kitchen floor (it was Sunday, or they’d have been boiling laundry). A rescue squad was despatched. Maddie was sent further down the lane on her bike to the bottom of the hill where there was a pub and a phone box.

‘She’ll need an ambulance, tha knows, love,’ the farmer’s wife had said to Maddie kindly. ‘She’ll need to go to hospital if she’s been flying an aeroplane.’

The words rattled around in Maddie’s head all the way to the telephone. Not ‘She’ll need to go to hospital if she’s been injured,’ but ‘She’ll need to go to hospital if she’s been flying an aeroplane.’

A flying girl! thought Maddie. A girl flying an aeroplane!

No, she corrected herself; a girl not flying a plane. A girl tipping up a plane in a sheep field.

But she flew it first. She had to be able to fly it in order to land it (or crash it).

The leap seemed logical to Maddie.

I’ve never crashed my motorbike, she thought. I could fly an aeroplane.

There are a few more types of aircraft that I know, but what comes to mind is the Lysander. That is the plane Maddie was flying when she dropped me here. She was actually supposed to land the plane, not dump me out of it in the air. We got fired at on the way in and for a while the tail was in flames and she couldn’t control it properly, and she made me bail out before she tried to land. I didn’t see her come down. But you showed me the photos you took at the site, so I know that she has crashed an aeroplane by now. Still, you can hardly blame it on the pilot when her plane gets hit by anti-aircraft fire.

Some British Support for Anti-Semitism

The Puss Moth crash was on Sunday. Beryl was back to work at the mill in Ladderal the next day. My heart twists up and shrivels with envy so black and painful that I spoiled half this page with tears before I realised they were falling, to think of Beryl’s long life of loading shuttles and raising snotty babies with a beery lad in an industrial suburb of Manchester. Of course that was in 1938 and they have all been bombed to bits since, so perhaps Beryl and her kiddies are dead already, in which case my tears of envy are very selfish. I am sorry about the paper. Miss E. is looking over my shoulder as I write and tells me not to interrupt my story with any more apologies.

Over the next week Maddie pieced together the pilot’s story in a storm of newspaper clippings with the mental wolfishness of Lady Macbeth. The pilot’s name was Dympna Wythenshawe (I remember her name because it is so silly). She was the spoiled youngest daughter of Sir Somebody-or-other Wythenshawe. On Friday there was a flurry of outrage in the evening paper because as soon as she was released from hospital, she started giving joyrides in her other aeroplane (a Dragon Rapide – how clever am I), while the Puss Moth was being mended. Maddie sat on the floor in her granddad’s shed next to her beloved Silent Superb, which needed a lot of tinkering to keep it in a fit state for weekend outings, and fought with the newspaper. There were pages and pages of gloom about the immediate likelihood of war between Japan and China, and the growing likelihood of war in Europe. The nose-down Puss Moth in the farmer’s field on Highdown Rise was last week’s news though; there were no pictures of the plane on Friday, only a grinning mugshot of the aviatrix herself, looking happy and windblown and much, much prettier than that idiot Fascist Oswald Mosley, whose sneering face glared out at Maddie from the prime spot at the top of the page. Maddie covered him up with her mug of cocoa and thought about the quickest way to get to Catton Park Aerodrome. It was a good distance, but tomorrow was Saturday again.

Maddie was sorry, the next morning, that she hadn’t paid more attention to the Oswald Mosley story. He was there, there in Stockport, speaking in front of St Mary’s on the edge of the Saturday market, and his idiot Fascist followers were having their own march to meet him, starting at the town hall and ending up at St Mary’s, causing traffic and human mayhem. They had by then toned down their anti-Semitism a bit and this rally was supposed to be in the name of Peace, believe it or not, trying to convince everybody that it would be a good idea to keep things cordial with the idiot Fascists in Germany. The Mosleyites were no longer allowed to wear their tastelessly symbolic black shirts – there was now a law in place about public marching in political uniforms, mainly to stop the Mosleyites causing riots like the ones they started with their marches through Jewish neighbourhoods in London. But they were going along to cheer for Mosley anyway. There was a happy crowd of his lovers and an angry crowd of his haters. There were women with baskets trying to get their shopping done at the Saturday market. There were policemen. There was livestock – some of the policemen were on horseback, and there was a herd of sheep being shunted through also on the way to market, and a horse-drawn milk cart stuck in the middle of the sheep. There were dogs. Probably there were cats and rabbits and chickens and ducks too.

Maddie could not get across the Stockport Road. (I don’t know what it’s really called. Perhaps that’s its right name because it’s the main road in from the south. You should not rely on any of my directions.) Maddie waited and waited on the edge of the simmering crowd, looking for a gap. After twenty minutes, she began to get annoyed. There were people pressing against her from behind now, as well. She tried to turn her motorbike round, walking it by the handlebars, and ran into someone.

‘Oi! Mind where you’re pushing that bike!’

‘Sorry!’ Maddie looked up.

It was a crowd of thugs, black-shirted for the rally even though they could get arrested for it, hair slicked back with Brylcreem like a bunch of airmen. They looked Maddie up and down gleefully, pretty sure she would be easy bait.

‘Nice bike.’

‘Nice legs!’

One of them giggled through his nose. ‘Nice —.’

He used an ugly, unspeakable word, and I won’t bother to write it because I don’t think any of you would know what it means in English, and I certainly do not know the French or German for it. The thuggish lad used it like a goading stick and it worked. Maddie shoved the front wheel of the bike past the one she had hit in the first place, and knocked into him again, and he grabbed the handlebars with his own big fists between her hands.

Maddie held on. They struggled for a moment over the motorbike. The boy refused to let go, and his mates laughed.

‘What’s a lass like you need with a big toy like this? Where’d you get it?’

‘At the bike shop, where d’you think!’

‘Brodatt’s,’ said one of them. There was only one on that side of town.

‘Sells bikes to Jews, he does.’

‘Maybe it’s a Jew’s bike.’

You probably don’t know it, but Manchester and its smoky suburbs have got quite a large Jewish population and nobody minds. Well, obviously some idiot Fascists do mind, but I think you see what I mean. They came from Russia and Poland and later Roumania and Austria, all Eastern Europe, all through the nineteenth century. The bike shop whose customers were in question happened to be Maddie’s granddad’s bike shop that he’d had for the last thirty years. He’d done quite well out of it, well enough to keep Maddie’s stylish gran in the manner to which she is accustomed, and they live in a large old house in Grove Green on the edge of the city and have a gardener and a daily girl to do the housekeeping. Anyway when this lot started slinging venom at Maddie’s granddad’s shop, Maddie unwisely engaged in battle with them and said, ‘Does it always take all three of you to complete a thought? Or can you each do it without your mates if you have enough time to think it over first?’

They pushed the bike over. It took Maddie down with it. Because bullying is what idiot Fascists like best.

But there was a swell of noisy outrage from other people in the crowded street, and the little gang of thugs laughed again and moved on. Maddie could hear the one lad’s distinctive nasal whinny even after his back had become anonymous.

More people than had knocked her down came to her aid, a labourer and a girl with a pram and a kiddie and two women with shopping baskets. They hadn’t fought or interfered, but they helped Maddie up and dusted her off and the workman ran loving hands down the Silent Superb’s mudguard. ‘Tha’s not hurt, miss?’

‘Nice bike!’

That was the kiddie. His mum said quickly, ‘Oi, you hush,’ because it was a perfect echo of the black-shirted youth who had pushed Maddie over.

‘’Tis nice,’ said the man.

‘It’s getting old,’ Maddie said modestly, but pleased.