Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Ghostland»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Edward Parnell 2019

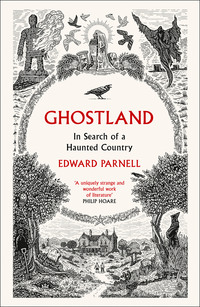

Cover illustrations and chapter initial illustrations are by Richard Wells (www.richardwellsgraphics.com)

All other images are by the author, or from the author’s own collection. While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material, in some cases this has proved impossible. The publishers would be grateful for any information that would allow any omissions to be rectified in future editions of this book.

Edward Parnell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Emigrants by WG Sebald published by Harvill Press, reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. © 1996

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008271992

eBook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008271961

Version: 2020-12-03

Dedication

For the ghosts

Epigraph

‘And so they are ever returning to us, the dead.’

W. G. Sebald, The Emigrants

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Epigraph

6 Contents

7 Prologue

8 1 LOST HEART

9 2 DARK WATERS

10 3 WALKING IN THE WOOD

11 4 THE ROARING OF THE FOREST

12 5 MEMENTO MORI

13 6 BORDERLAND

14 7 GOBLIN CITY

15 8 LONELIER THAN RUIN

16 9 WHO IS THIS WHO IS COMING?

17 10 NOT REALLY NOW NOT ANY MORE

18 11 TROUBLE OF THE ROCKS

19 12 ANCIENT SORCERIES

20 Epilogue

21 Selected List of Sources

22 Acknowledgements

23 Index

24 Also by Edward Parnell

25 About the Author

26 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivvvii1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367368369370371372373374375376377378379380381382383385386387388389390391392393394395396397398399400401402403404405406407408409410411412413414415416417418419420421422423424425426427428429430431433434435436437438439440441442443444445446447448451452453455456457458459460461462463464465466467ii

Prologue

Always the ghosts.

Reaching into the past concealed behind the glow-in-the-dark cardboard apparitions that decorated my childhood bedroom, the fascination was there from the start: on a family holiday to Wales, aged four, asking the tour guide in Caernarfon Castle whether we might see the place’s spectral lady; a few years later, obsessing over Borley Rectory – the ‘most haunted house in the world’ – which called out to me from my spine-creased Usborne Guide to the Supernatural World; or, at the Halloween party I begged my mother to let me have (long before such events were a commonplace British occurrence), dressing up as Dracula, my friends as the Wolfman and various grinning ghouls.

The writer M. R. James once wrote: ‘For the ghost story a slight haze of distance is desirable. “Thirty years ago,” “Not long before the war,” are very proper openings.’

And if I think back through three decades of self-obfuscation, a host of recollections give confirmation.

With me, always the ghosts.

Yet even with hindsight no disquiet comes to me from these memories; they are reassuring, I can find shelter within them. Only later were we to become a phantom family – a host of lives lived, then unlived. The disquiet comes when I realise there’s no one left to help me reconcile the real and the half-remembered.

So, I must do it myself.

I must attempt to explore that sense so many before me have felt. The shadows they too have glimpsed among the fields, hills and trees of this haunted land.

To lay to rest the ghosts of my own sequestered past.

Chapter 1

LOST HEART

It was, as far as I can ascertain, on Christmas Eve of the year 1994 that a young man drew up before the door of his childhood home, in the heart of Lincolnshire. He looked about him with the keenest curiosity during the short interval that elapsed between the fumbling of his keys and the opening of the front door. Inside, he began to study the four programmes available on his television set, pausing before a presentation that caught his eye. The time was five minutes before one o’clock, he realised. Christmas Day itself …

This, more or less, was how I first became acquainted with the work of M. R. James, my favourite – and arguably Britain’s finest – writer of ghost stories. I was home for the holidays during my third year at university and had been into town to celebrate the festivities. A little the worse for drink, I was alone in the living room, as my brother Chris – nearly six years my senior – was still out with friends. In the morning the two of us would open our presents together before spending the rest of the day at my aunt and uncle’s. In an attempt to compensate for the house’s emptiness and our parents’ absence, we’d started a tradition of labelling our gifts to each other as if from various half-remembered figures from our past: obscure family acquaintances, disliked former teachers, or people who we had given nicknames to – like Porkpie, the middle-aged man in the pork-pie hat who was a constant fixture in the pub we frequented, boring anyone who’d listen about the supermarket where he worked.

Not ready for sleep, I lay on the sofa and flicked through the TV channels. On BBC Two a grainy drama from the seventies was beginning. What I’d chanced upon was an episode of the classic ‘A Ghost Story for Christmas’ strand: Lawrence Gordon Clark’s adaptation of M. R. James’s supernatural tale ‘Lost Hearts’.

There’s a fearful symmetry to this, I’ve come to learn, because this particular film was first shown on BBC One a little before midnight on Christmas Day 1973, less than a fortnight after I was born. Had I already witnessed it as a crying baby – perhaps my mother had happened at that very point to switch on the TV set to try and calm my tears? If she had, I doubt she would have found much respite, because the BBC version is a frightening piece of work; I was to find this out some twenty-one years later, when the ghost of a razor-nailed boy and his dark-eyed companion appeared on the screen in front of me.

Through the white gate at the back of the graveyard the ground changes abruptly, the approach from the rectory with its aged, ivy-clad trees replaced by a squat jumble of shrubs and sedge, punctuated by paths that run aimlessly to the water. The ‘lake’, as it is called, seems out of place in the west Suffolk countryside, reminding me of one of the shallow, ephemeral coastal lagoons you find in the Camargue. Lifeless trunks point upwards from its greyness like rigor-mortised fingers. The division between land and water is tenuous; there are no banks as such, just a dirty shoreline of mud over which the waves lap, adding to the feature’s temporary feel. This is not a giant puddle left behind by a flood, or some deliberately drowned world, but a spring-fed mere that has given its name to the neighbouring village.

Livermere Lake. ‘The lake where rushes grow’, from the Old English laefor-mere. I’ve known about this place for a long time too: since my brother saw a vagrant black-winged pratincole here in 1993, a rare hawk-like wading bird. I couldn’t join him to see it, which, as a keen birdwatcher, riled me for years (until I finally caught up with one myself on the Norfolk coast) and lent the location an enduring mystique in my head. Only later did I become aware of the connection between Great Livermere and M. R. James.

Montague Rhodes James – known to his close friends as Monty – was born in Goodnestone, a small Kent village midway between Canterbury and Deal where his father was then curate, in August 1862. After three years the family moved to Livermere, six miles from Bury St Edmunds, when Herbert James took up the rectorship of St Peter’s Church, whose gravestones I passed between on my way to the mere. This section is Broad Water, with the narrow tree-lined southern arm, Ampton Water, snaking off somewhere behind me, obscured by a screen of trees. The rain slants sparsely down as I scan the surface and shore: there are no rare waders today, though a typically noisy pair of black-and-white oystercatchers flies past, splitting the silence with their piping.

Across the water stands a second church, the now-ruined St Peter and St Paul of Little Livermere, derelict since the first half of the twentieth century. The tower, according to James in his 1930 work Suffolk and Norfolk: A Perambulation of the Two Counties with Notices of their History and their Ancient Buildings, was heightened so as to be seen from Livermere Hall, itself long gone, demolished as superfluous in 1923. Its owner, Jane Anne Broke, was a relative by marriage of Herbert James, which was how he came to be offered the role of attending to the spiritual needs of the village – a serendipitous move in terms of its influence on young Monty’s future ghost stories. Stately homes and their surrounding parkland appear in a number of those tales, reflecting James’s upbringing as the son of a well-connected rector and the privileged circles in which he was to circulate during his later career as provost of both Cambridge’s King’s College and Eton’s famous public school.*

In ‘Lost Hearts’, the young protagonist Stephen Elliott stands at his open window listening to the strange noises coming from across the mere: ‘They might be the notes of owls or water-birds, yet they did not quite resemble either.’ The lake is rich with bird life, and it’s easy to picture the youthful James kept awake by their sounds – distorted by the space between mere and rectory – as he lay in his bedroom searching for sleep. Monty, however, appeared fond of his childhood home – various surviving fragments of juvenilia extol the virtues, and to an extent the eeriness, of the local landscape. In the undated poem ‘Sounds of the Wood’ he begins:

From off the mere, above the oaks, the hern

Come sailing, and the rook fly cawing home.

The scene in front of me is little changed from that which the young James took pleasure in over a century ago. Sure enough, a heron is present this afternoon (‘hern’ is an archaic form of the word), roosting in the alders beside Ampton Water. A striking adult bird, its blue-grey plumage is broken up by its black-feathered shoulder and the thick stripe that extends above its eye.

I walk back towards the church of James’s father. A small deer – a muntjac, I presume – peers at me from through the sedges, sliding beneath the cover of a sallow before I can get a proper look. In the churchyard I wander among the headstones, one ghosted with the faint outline of a cherubic face, another with a lichen-covered skeleton. The commonest surname I find is Mothersole, the name James bestowed upon the witch from his story ‘The Ash Tree’. The horrifying Mrs Mothersole goes on to enact a spidery revenge on the descendants of Sir Matthew Fell, the man responsible for her hanging, delivering a chilling rebuke as she stands on the gallows awaiting her fate: ‘There will be guests at the Hall.’ ‘The Ash Tree’ is set in Suffolk, and a mere features in the grounds of the fictitious Castringham Hall; it’s not unreasonable to suppose that the now-vanished house across the park from James’s childhood home might have been the model for the story’s location.

Alongside the grave of Charles and Ann Mothersole I find the remains of a blackbird, dead a week or so and becoming one with the surrounding soil and oak leaves. Banding its leg is an identification ring from the Natural History Museum. Later, I learn the bird’s melancholy fate: ringed in Great Livermere as a fledgling the previous spring, barely moving from its place of birth.

Towards the back of the churchyard, beyond a dark rectangle of yews (which bring to mind the whispering grove from James’s story ‘The Rose Garden’), stands a spindly cross. This might be the memorial to his mother and father that James had erected. I look for the word ‘PAX’, which is meant to be inscribed on it, but can only make out the letters IHS at its apex: Jesus, saviour of mankind. The stone is crusted with pale-green moss, obscuring the writing on its base. I start to flake off the material with my fingernail in an attempt to expose further clues. There is an inscription, though it’s not easy to read – and something about the act of uncovering it feels wrong, like the sort of foolish feat an inquisitive scholar in one of James’s stories would do and later come to regret.

I decide to leave it a mystery.

Returning to where I parked my car by the front gate of the churchyard, I peer over a wall, through the rhododendrons on the other side, at a cream-coloured building. It’s James’s childhood home – a square, solid-looking place rising to three storeys, with plenty of rooms for the young James to have lost himself in on the occasions he was here and not away at Temple Grove prep school, on the outskirts of London between Mortlake and Richmond Park. This was followed by Eton, where in 1882, and already writing his own ghost stories (as well as indulging in more serious sixth-form study, including a love of the classics, ancient manuscripts and the architecture of churches), he passed his scholarship exam for King’s College, Cambridge.

I contemplate the chances of being allowed to take a closer look at the rectory, restyled as the new Livermere Hall and used as accommodation for expensive game-shooting trips, but decide that rocking up unannounced is unlikely to gain me a warm welcome and an offer of the full guided tour (I tried the same earlier, without success, at the farm neighbouring the derelict church of Little Livermere). Besides, the daylight is waning and the rain now falling more keenly. As I drive from the village, past the dark earth of countless ploughed-open fields, the final words of James’s last published story, ‘A Vignette’, resonate:

Are there here and there sequestered places which some curious creatures still frequent, whom once on a time anybody could see and speak to as they went about on their daily occasions, whereas now only at rare intervals in a series of years does one cross their paths and become aware of them?†

‘Lost Hearts’ was probably the second of James’s published ghost stories to be written (after ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book’), finished at some time between summer 1892 and autumn of the following year. It appeared in print in the Pall Mall Magazine in December 1895, then in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, his first collection of supernatural tales, in 1904.

By this point, James had been made a dean (of King’s) and, from 1893, the director of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum. In addition to an expert command of Latin, Greek and French, he also had a familiarity with German and Italian – and even a modicum of Hebrew and Danish. These formidable linguistic skills served him admirably: he was a noted scholar of the medieval, and of esoteric branches of study such as biblical apocrypha – the sorts of subjects the lone middle-aged protagonists of his stories specialise in. Now in his early forties – though always, perhaps, appearing a little older than his years – James was a tall, well-built man with dark hair (parted to the right) and rounded spectacles. His features were soft, apart from a strong, square jaw. He spoke quietly, often chuckling, often drawing on his curved tobacco pipe.

Photo (M. R. James) Hulton Archive/Stringer via Getty Images

I knock and enter the opaque-paned door to the Founder’s Library of the Fitzwilliam. Inside the architecture appears largely unchanged since James’s time, when the room acted as his office. Built in 1848, it houses ten thousand fine volumes in carved oak bookcases that stretch more than twenty feet up to the white, geometrically patterned ceiling. An imposing marble-surrounded fireplace dominates the room. It’s a place of work and study where today the museum’s manuscript department is based – something James would approve of, I’m sure. A young woman at a table is leafing through an oversized illuminated book of musical scores, the only sound apart from the occasional swish of turning pages being the background hum of a dehumidifier. It is a soporific, comforting space that sends me back to another time, another world – and it’s easy on this darkening winter’s afternoon to imagine the director at his desk, squinting through his glasses in the pooled light at one of the antiquated tomes that line the vast shelves.‡

James himself appeared rather indifferent to ‘Lost Hearts’, writing to his friend James McBryde in March 1904 that ‘I don’t much care about it.’ The same was not true of Monty’s feelings for the man who was to become the illustrator of his first collection of ghost stories, his affection rising from the page as he later described McBryde in glowing terms: ‘no one who, even when he supposed himself out of spirits, brought so much enjoyment into an expedition. A smile will never be far off when his friends speak of him …’

Photo by the author, reproduction by permission of the Syndics of The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

James McBryde was a decade younger than MRJ – the three initials were how James usually signed his own name, and how he was referred to by many acquaintances – arriving at King’s College, Cambridge from Shrewsbury in 1893 to study medicine (‘Natural Sciences’ as it was then known). The dashing McBryde came to be a close companion to James, joining him on summer cycling trips, including those to Denmark and Sweden that provided the setting for the stories ‘Number 13’ and ‘Count Magnus’. After completing his medical studies in tribute to the wishes of his late father (though caring little for the subject), McBryde took up a place at the Slade School in 1903 to commence his formal artistic training – a calling for which it is clear he had a considerable talent. Early in the following year, however, he became seriously ill with appendicitis, and a second attack followed in March.

During his friend’s recuperation, James welcomed the idea that McBryde should illustrate some of his stories for the book that was to become Ghost Stories of an Antiquary – stories James had previously read out on Christmas Eve, by the light of a single candle, to the assembled King’s choristers and his fellow academics and acquaintances of the Chitchat Society. In carrying on a loose tradition popularised by Charles Dickens, the Cambridge don became the unwitting new keeper of the seasonal, supernatural flame. In folklore, ghosts had long been linked with Christmas Eve – a night, like Halloween, in which the boundary between this world and the Otherworld, the realm of the spirits, is said to be thinned. And though the festive telling of ghostly stories clearly took place before Dickens – dark winter nights lend themselves to it – the Victorian writer had brought the practice into the mainstream through A Christmas Carol and the tales he published in his own weekly magazine, Household Words.

Perhaps the most effective of these is ‘No. 1 Branch Line: The Signalman’. It too was produced specially for Christmas, as was the 1976 BBC version directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, the first of the ‘Ghost Story for Christmas’ films not to have been adapted from one of James’s stories. The Signalman features a superb performance from Denholm Elliott, whose terrifying vision of his future may well be the most frightening sequence in the entire strand. The story features three supernaturally foretold railway accidents, and it seems no coincidence that it was written the year after Dickens was himself an unwilling participant in such an event.

Illustrated London News, 1865 (Wikimedia Commons)

On 9 June 1865, returning from France through Kent en route to Charing Cross, the train he was travelling in came to a low viaduct at Staplehurst that was in the process of being repaired. Several carriages plunged off the tracks, killing ten people and injuring fifty, although the structure stood only around ten feet above the muddy stream below; at the moment of derailment Dickens was reading through the manuscript of Our Mutual Friend. As the writer and his mistress, the actress Ellen Ternan, were at the front of the vehicle in first class, they got off relatively lightly. However, Ternan suffered physical injuries that incapacitated her for weeks, while Dickens, who helped to comfort other passengers, was traumatised, and nervous of train travel thereafter. And, in an odd twist, his own death (resulting from a stroke) was to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the accident.

James McBryde completed only four drawings for Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. He died in early June 1904, five days after having his appendix operated on. James’s book was published at the end of that year, with his friend’s illustrations embellishing ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book’ and ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’. In his preface James paid tribute to its illustrator: ‘Those who knew the artist will understand how much I wished to give a permanent form even to a fragment of his work.’ Despite his Victorian, repressed reluctance to display his emotions, Monty was devastated by the death of McBryde, picking rose, honeysuckle and lilac blooms from the Fellows’ Garden at King’s, and taking them with him on the train to the funeral in Lancashire.§ He cast them into his friend’s grave after the other mourners had departed.

Original illustrations by James McBryde (1874–1904) from the first edition of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by M. R. James

James’s sexuality has long been the subject of speculation – he was a lifelong bachelor, and surrounded himself with close, often younger, male friends. Those searching for Freudian clues about his personal life might point to the lack of female protagonists in his stories, or note that when women do appear they regularly take the role of the fiend, like Mrs Mothersole in ‘The Ash Tree’. The academic Darryl Jones refers to the ‘mouth, with teeth, and with hair about it’ inside which Mr Dunning in ‘Casting the Runes’ unsuspectingly places his hand, in the nook beneath his pillow, as a ‘vagina dentata – a nightmare image of the monstrous-feminine’. A similar horror could be ascribed to the mouldy well-cavity and the guardian-thing it harbours (‘more or less like leather, dampish it was’) in ‘The Treasure of Abbot Thomas’.

Both of these examples may indeed, possibly, point to a fear of (or at least unfamiliarity with) women, and therefore may be indicative of James’s clandestine fears or desires. Undoubtedly, having spent his life in all-male academia, he was far more comfortable in the company of men. This stretched to an enjoyment of the rough wrestling-games of ‘ragging’ and ‘animal grab’ that he played at Eton and continued to engage in while at King’s – at the meetings of the TAF (‘Twice a Fortnight’) society, or at college Christmas Eve parties. James’s friend Cyril Alington, later the headmaster of Eton (while James was its provost), provides surprising evidence contradicting the image of James as a stilted academic who we might expect to shun such physical contact; he recalled another friend, St Clair Donaldson – the future bishop of Salisbury – rolling on the floor during one of these games ‘with Monty James’s long fingers grasping at his vitals’.

James’s tactile nature is reflected in his stories, in which the protagonists often experience the touch or feel of something that causes them revulsion, or, in the case of Stephen in ‘Lost Hearts’, wake to find his nightgown has been shredded in the darkness by the raking fingers of the ghost-boy Giovanni. However, it would be presumptuous to assume that these horrors result from some subconscious psychosexual terror experienced by James – they may have been chosen simply for their unpleasantness, or for their resemblance to the medieval visions of Hell garishly on display in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and also prevalent in the manuscripts of that period and the biblical apocrypha of which James was such a keen scholar.

Detail from Dulle Griet by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Wikimedia Commons)

Because it strikes me that an unexpected toothed mouth appearing beneath a pillow would be equally terrifying to any sleeper, regardless of whether they were a man or a woman, gay or straight.

Gordon Carey, a former King’s chorister and Cambridge student who was one of James’s closest later friends, told his son long after James’s death that he supposed Monty was ‘what would now be called a non-practising homosexual’.¶ However, a definitive answer to the question of the writer’s sexuality – something that is ultimately irrelevant in relation to our enjoyment of his stories – seems likely to remain unknowable.

The reticence about ‘Lost Hearts’ that MRJ voiced to James McBryde perhaps hints at the atypical nature of the tale. In some ways it’s grubbier and nastier than most of his stories – which might explain James’s apparent disdain for it.** One of its main characters is a child – and children rarely feature in his work. Before the action begins, the real devil of the piece, Mr Abney, has already lured two adolescents to his grand house, removing their still-beating hearts with a knife while they lie drugged before him, then eating the organs accompanied by a glass of fine port. He plans to confer the same grim fate upon his young orphaned cousin Stephen Elliott in a ritual attempt to attain special powers for himself: invisibility, the ability to take on other forms, and the capacity for flight.

I disagree with James’s own lukewarm opinion of ‘Lost Hearts’. The story is viscerally effective in exploring the loss of childhood innocence (and of the boundaries people will cross to achieve their aims), though I think the adaptation I happened upon on that distant Christmas Eve is in some ways the more frightening of the two versions: certainly the gypsy girl Phoebe and the Italian boy Giovanni make petrifying on-screen apparitions with their greyish-blue skin, yellowed teeth, weirdly hypnotic swaying, and those extraordinary claw-like fingers. The maniacal movement of Mr Abney – he’s usually filmed with the camera tracking him, or circling Stephen in the way a big cat circles its prey – was inspired by Robert Wiener’s fêted work of German Expressionism, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. And, in the appearance of the two ghost children, I see echoes of another silent German classic, F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, in which Max Schreck’s depiction of the spindly-fingered vampire, Count Orlok, remains one of the most iconic images of the supernatural committed to celluloid.

Yet, above all in the small-screen version, it was the ghost-boy’s hurdy-gurdy music that I found most unsettling. The film had no budget for an orchestral score, with scratchy vinyl 78s from the BBC archives providing the unforgettable aural chills; the adaptation makes no attempt, however, to replicate the ‘hungry and desolate cries’ of the dreadful pair of ghosts, a savage detail in James’s original.

Ullstein bild Dtl./Contributor via Getty Images