Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Hexwood»

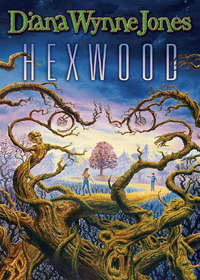

Diana Wynne Jones

HEXWOOD

ILLUSTRATED BY TIM STEVENS

Copyright

First published by Methuen Children’s Books Ltd 1993

First published in paperback by Collins 2000

Published by HarperCollins Children’s Books

1 London Bridge Street,

London, SE1 9GF

Text copyright © Diana Wynne Jones 1993

Illustration by Tim Stevens 2000

The author and illustrator assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of the work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006755265

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2012 ISBN: 9780007440184

Version: 2018-06-21

Dedication

For Neil Gaiman

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PART ONE

1

2

3

4

5

PART TWO

1

2

3

4

5

PART THREE

1

2

3

4

5

PART FOUR

1

2

3

4

5

PART FIVE

1

2

3

4

5

PART SIX

1

2

3

4

5

PART SEVEN

1

2

3

4

5

PART EIGHT

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

PART NINE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Other Works

About the Publisher

The letter was in Earth script, unhandily scrawled in blobby blue ballpoint. It said:

Hexwood Farm

Wednesday 3 March 1993

Dear Sector Controller,

We though we better send to you in Regional straight off. We got a right problem here. This fool clerk, calls hisself Harrison Scudmore, he went and started one of these old machines running, the one with all the Reigner seals on it, says he overrode the computers to do it. When we say a few words about that, he turns round and says he was bored, he only wanted to make the best all-time football team, you know King Arthur in goal, Julius Ceasar for striker, Napoleon midfield, only this team is for real, he found out this machine can do that, which it do. Trouble is we don’t have the tools nor the training to get the thing turned off, nor we can’t see where the power’s coming from, the thing’s got afield like you wouldn’t believe and it won’t let us out of the place. Much obliged if you could send a trained operative at your earliest convenience.

Yours truly

W. Madden

Foreman Rayner Hexwood Maintenance

(European Division)

PS He says he’s had it running more than a month now.

Sector Controller Borasus stared at the letter and wondered if it was a hoax. W. Madden had not known enough about the Reigner Organisation to send his letter through the proper channels. Only the fact that he had marked his little brown envelope URGENT!!! had caused it to arrive in the Head Office of Albion Sector at all. It was stamped all over with queries from branch offices and had been at least two weeks on the way.

Controller Borasus shuddered slightly. A machine with Reigner seals! If this was not a hoax, it was liable to be very bad news. “It must be someone’s idea of a joke,” he said to his Secretary. “Don’t they have something called April Fools’ Day on Earth?”

“It’s not April there yet,” his Secretary pointed out dubiously. “If you recollect, sir, the date on which you are due to attend their American conference – tomorrow, sir – is 20 March.”

“Then maybe the joker mistimed his letter,” Controller Borasus said hopefully. As a devout man who believed in the Divine Balance perpetually adjusted by the Reigners, and himself as the Reigners’ vicar on Albion, he had a strong feeling that nothing could possibly go really wrong. “What is this Hexwood Farm thing of theirs?”

His Secretary as usual had all the facts. “A library and reference complex,” he answered, “concealed beneath a housing estate not far from London. I have it marked on my screen as one of our older installations. It’s been there a good twelve hundred years, and there’s never been any kind of trouble there before, sir.”

Controller Borasus sighed with relief. Libraries were not places of danger. It had to be a hoax. “Put me through to the place at once.”

His Secretary looked up the codes and punched in the symbols. The Controller’s screen lit with a spatter of expanding lights. It was not unlike what you see when you press your fingers into your eyes.

“Whatever’s that?” said the Controller.

“I don’t know, sir. I’ll try again.” The Secretary cancelled the call and punched the code once more. And again after that. Each time the screen filled with a new flux of expanding shapes. On the Secretary’s third attempt, the coloured rings began spreading off the viewscreen and rippling gently outwards across the panelled wall of the office.

Controller Borasus leant across and broke the connection, fast. The ripples spread a little more, then faded. The Controller did not like the look of it at all. With a cold, growing certainty that everything was not all right after all, he waited until the screen and the wall at last seemed back to normal and commanded, “Get me Earth Head Office.” He could hear that his voice was half an octave higher than usual. He coughed and added, “Runcorn, or whatever the place is called. Tell them I want an explanation at once.”

To his relief, things seemed quite normal this time. Runcorn came up on the screen, looking entirely as it should, in the person of a Junior Executive with beautifully groomed hair and a smart suit, who seemed very startled to see the narrow, august face of the Sector Controller staring out of the screen at him, and even more startled when the Controller asked to speak to the Area Director instantly. “Certainly, Controller. I believe Sir John has just arrived. I’ll put you through—”

“Before you do,” Controller Borasus interrupted, “tell me what you know about Hexwood Farm.”

“Hexwood Farm!” The Junior Executive looked nonplussed. “Er – you mean – Is this one of our information retrieval centres you have in mind, Controller? I think one of them is called something like that.”

“And do you know a maintenance foreman called W. Madden?” demanded the Controller.

“Not personally, Controller,” said the Junior Executive. It was clear that if anyone else had asked him this question, the Junior Executive would have been very disdainful indeed. He said cautiously, “A fine body of men, Maintenance. They do an excellent job servicing all our offworld machinery and supplies, but of course, naturally, Controller, I get into work some hours after they’ve—”

“Put me through to Sir John,” sighed the Controller.

Sir John Bedford was as surprised as his Junior Executive. But after Controller Borasus had asked only a few questions, a slow horror began to creep across Sir John’s healthy businessman’s face.

“Hexwood Farm is not considered very important,” he said uneasily. “It’s all history and archives there. Of course that does mean that it holds a number of classified records – it has all the early stuff about why the Reigner Organisation keeps itself secret here on Earth – how the population of Earth arrived here as deported convicts and exiled malcontents, and so forth – and I believe there is a certain amount of obsolete machinery stored there too – but I can’t see how our clerk would be able to tamper with any of that. We run it through just the one clerk, you see, and he’s pretty poor stuff, only in the Grade K information bracket—”

“And Grade K means?” asked Controller Borasus.

“It means he’ll have been told that Rayner Hexwood International is actually an intergalactic firm,” Sir John explained, “but that should be absolutely all he knows – probably less than Maintenance, who are also Grade K. Maintenance pick up a thing or two in the course of their work. That’s unavoidable. They visit every secret installation once a month to make sure everything stays in working order, and to supply the stass-stores with food and so forth, and I suspect quite a few of them know far more than they’ve been told, but they’ve been carefully tested for loyalty. None of them would play a joke like this.”

Sir John, Controller Borasus decided, was trying to talk himself out of trouble. Just what you would expect from a backward hole like Earth. “So what do you think is the explanation?”

“I wish I knew,” said the Director of Earth. “Oddly enough, I have two complaints on my desk just this morning. One is from an Executive in Rayner Hexwood Japan, saying that Hexwood Farm is not replying to any of his repeated requests for data. The other is from our Brussels branch, wanting to know why Maintenance has not yet been to service their power plant.” He stared at the Controller, who stared back. Each seemed to be waiting for the other to explain. “That foreman should have reported to me,” Sir John said at length, rather accusingly.

Controller Borasus sighed. “What is this sealed machine that seems to have been stored in your retrieval centre?”

It took Sir John Bedford five minutes to find out. What a slack world! Controller Borasus waited, drumming his fingers on the edge of his console, and his Secretary sat not daring to get on with any other business.

At last Sir John came back on the screen. “Sorry to be so long. Anything with Reigner seals here is under heavy security coding, and there turn out to be about forty old machines stored in that library. We have this one listed simply as One Bannus, Controller. That’s all, but it must be the one. All the other things under Reigner seals are stass-tombs. I imagine there’ll be more about this Bannus in your own Albion archives, Controller. You have a higher clearance than—”

“Thank you,” snapped Controller Borasus. He cut the connection and told his Secretary, “Find out, Giraldus.”

His Secretary was already trying. His fingers flew. His voice murmured codes and directives in a continuous stream. Symbols scrolled, and vanished, and flickered, jumping from screen to screen, where they clotted with other symbols and jumped back to enter the main screen from four directions at once. After a mere minute, Giraldus said, “It’s classified maximum security here too, sir. The code for your Key comes up on your screen – now.”

“Thank the Balance for some efficiency!” murmured the Controller. He took up the Key that hung round his neck from his chain of office and plugged it into the little-used slot at the side of his console. The code signal vanished from his screen and words took its place. The Secretary of course did not look, but he saw that there were only a couple of lines on the screen. He saw that the Controller was reacting with considerable dismay. “Not very informative,” Borasus murmured. He leant forward and checked the line of symbols which came up after the words in the smaller screen of his manual. “Hm. Giraldus,” he said to his Secretary.

“Sir?”

“One of these is a need-to-know. Since I’m going to be away tomorrow, I’d better tell you what this says. This W. Madden seems to have his facts right. A Bannus is some sort of archaic decision-maker. It makes use of a field of theta-space to give you live-action scenarios of any set of facts and people you care to feed into it. Acts little plays for you, until you find the right one and tell it to stop.”

Giraldus laughed. “You mean the clerk and the maintenance team have been playing football all this month?”

“It’s no laughing matter.” Controller Borasus nervously snatched his Key from its slot. “The second code symbol is the one for extreme danger.”

“Oh.” Giraldus stopped laughing. “But, sir, I thought theta-space—”

“—was a new thing the central worlds were playing with?” the Controller finished for him. “So did I. But it looks as if someone knew about it all along.” He shivered slightly. “If I remember rightly, the danger with theta-space is that it can expand indefinitely if it’s not controlled. I’m the Controller,” he added with a nervous laugh. “I have the Key.” He looked down at the Key, hanging from its chain. “It’s possible that this is what the Key is really for.” He pulled himself together and stood up. “I can see it’s no use trusting that idiot Bedford. It will be extremely inconvenient, but I had better get to Earth now and turn the wretched machine off. Notify America, will you? Say I’ll be flying on from London after I’ve been to Hexwood.”

“Yes, sir.” Giraldus made notes, murmuring. “Official robes, air tickets, passport, standard Earth documentation-pack. Is that why I need to know, sir?” he asked, turning to flick switches. “So that I can tell everyone you’ve gone to deal with a classified machine and may be a little late getting to the conference?”

“No, no!” Borasus said. “Don’t tell anyone. Make some other excuse. You need to know in case Homeworld gets back to you after I’ve left. The first symbol means I have to send a report top priority to the House of Balance.”

Giraldus was a pale and beaky man, but this news made him turn a curious yellow. “To the Reigners?” he whispered, looking like an alarmed vulture.

Controller Borasus found himself clutching his Key as if it was his hope of salvation. “Yes,” he said, trying to sound firm and confident. “Anything involving this machine has to go straight to the Reigners themselves. don’t worry. No one can possibly blame you.”

But they can blame me, Borasus thought, as he used his Key on the private emergency link to Homeworld, which no Sector Controller ever used unless he could help it. Whatever this is, it happened in my sector.

The emergency screen blinked and lit with the symbol of the Balance, showing that his report was now on its way to the heart of the galaxy, to the almost legendary world that was supposed to be the original home of the human race, where even the ordinary inhabitants were said to be gifted in ways that people in the colony worlds could hardly guess at. It was out of his hands now.

He swallowed as he turned away. There were supposed to be five Reigners. Borasus had worried, double thoughts about them. On one hand, he believed almost mystically in these distant beings who controlled the Balance and infused order into the Organisation. On the other hand, as he was accustomed to say drily to those in the Organisation who doubted that the Reigners existed at all, there had to be someone in control of such a vast combine, and whether there were five, or less, or more, these High Controllers did not appreciate blunders. He hoped with all his heart that this business with the Bannus did not strike them as a blunder. What – he told himself – he emphatically did not believe were all these tales of the Reigners’ Servant.

When the Reigners were displeased, it was said, they were liable to dispatch their Servant. The Servant, who had the face of death and dressed always in scarlet, came softly stalking down the stars to deal with the one who was at fault. It was said he could kill with one touch of his bone-cold finger, or at a distance, just with his mind. It did no good to conceal your fault, because the Servant could read minds, and no matter how far you ran and how many barriers you put between, the Servant could detect you and come softly walking through anything you put in his way. You could not kill him, because he deflected all weapons. And the Servant would never swerve from any task the Reigners appointed him to.

No, Controller Borasus did not believe in the Servant – although, he had to admit, there were quite frequent dry little reports that came into Albion Head Office to the effect that such-and-such an executive, or director, or sub-consul, had terminated from the Organisation. No, that was something different. The Servant was just folklore.

But I shall take the rap, Borasus thought as he went to get ready to go to Earth, and he shivered as if a blood-red shadow had walked softly on bone feet across his grave.

A boy was walking in a wood. It was a beautiful wood, open and sunny. All the leaves were small and light green, hardly more than buds. He was coming down a mud path between sprays of leaves, with deep grass and bushes on either side.

And that was all he knew.

He had just noticed a small tree ahead that was covered with airy pink blossom. He looked beyond it. Though all the trees were quite small and the wood seemed open, all he could see was this wood, in all directions. He did not know where he was. Then he realised that he did not know where else there was to be. Nor did he know how he had got to the wood in the first place. After that, it dawned on him that he did not know who he was. Or what he was. Or why he was there.

He looked down at himself. He seemed quite small – smaller than he expected somehow – and rather skinny. The bits of him he could see were wearing faded purple-blue. He wondered what the clothes were made of and what held the shoes on.

“There’s something wrong with this place,” he said. “I’d better go back and try to find the way out.”

He turned back down the mud path. Sunlight glittered on silver there. Green reflected crazily on the skin of a tall silver man-shaped creature pacing slowly towards him. But it was not a man. Its face was silver and its hands were silver too. This was wrong. The boy took a quick look at his own hands to be sure, and they were brownish-white.

This was some kind of monster. Luckily there was a green spray of leaves between him and the monster’s reddish eyes. It did not seem to have seen him yet. The boy turned and ran quietly and lightly, back the way he had been coming from.

He ran hard until the silver thing was out of sight. Then he stopped, panting, beside a tangled patch of dead briar and whitish grass, wondering what he had better do. The silver creature walked as if it were heavy. It probably needed the beaten path to walk on. So the best idea was to leave the path. Then if it tried to chase him it would get its heavy feet tangled.

He stepped off the path into the patch of dried grass. His feet seemed to cause a lot of rustling in it. He stood still, warily, up to his ankles in dead stuff, listening to the whole patch rustling and creaking.

No, it was worse! Some dead brambles near the centre were heaving up. A long light-brown scaly head was sliding forward out of them. A scaly foreleg with long claws stepped forward in the grass beside the head, and another leg, on the other side. Now the thing was moving slowly and purposefully towards him, the boy could see it was – crocodile? pale dragon? – nearly twenty feet long, dragging through the pale grass behind the scaly head. Two small eyes near the top of that head were fixed upon him. The mouth opened. It was black inside and jagged with teeth, and the breath coming out smelt horrible.

The boy did not stop to think. Just beside his feet was a dead branch, overgrown and half-buried in the grass. He bent down and tore it loose. It came up trailing roots, falling to pieces, smelling of fungus. He flung it, trailing bits and all, into the animal’s open mouth. The mouth snapped on it, and could only shut halfway. The boy turned and ran and ran. He hardly knew where he went, except that he was careful to keep to the mud path.

He pelted round a corner and ran straight into the silver creature.

Clang.

It swayed and put out a silver hand to fend him off. “Careful!” it said in a loud flat voice.

“There’s a crawling thing with a huge mouth back there!” the boy said frantically.

“Still?” asked the silver creature. “It was killed. But maybe we have yet to kill it, since I see you are quite small just now.”

This meant nothing to the boy. He took a step back and stared at the silver being. It seemed to be made of bendable metal over a man-shaped frame. He could see ridges here and there in the metal as it moved, as if wires were pulling or stretching. Its face was made the same way, sort of rippling as it spoke – except for the eyes, which were fixed and reddish. The voice seemed to come from a hole under its chin. But now he looked at it closely, he saw it was not silver quite all over. There were places where the metal skin had been patched, and the patches were disguised with long strips of black and white trim, down the silver legs, round the silver waist and along the outside of each gleaming arm.

“What are you?” he asked.

“I am Yam,” said the being, “one of the early Yamaha robots, series nine, which were the best that were ever made.” It added, with pride in its flat voice, “I am worth a great deal.” Then it paused, and said, “If you do not know that, what else do you not know?”

“I don’t know anything,” said the boy. “What am I?”

“You are Hume,” said Yam. “That is short for human, which you are.”

“Oh,” said the boy. He discovered, by moving slightly, that he could see himself reflected in the robots shining front. He had fairish hair, grown longish, and he seemed to stand and move in a light, eager sort of way. The purple-blue clothes clung close to his skinny body from neck to ankles, without any sort of markings, and he had a pocket in each sleeve. Hume, he thought. He was not certain that was his name. And he hoped the shape of his face was caused by the robots curved front. Or did people’s cheekbones really stick out that way?

He looked up at Yam’s silver face. The robot was nearly two feet taller than he was. “How do you know?”

“I have a revolutionary brain and my memory is not yet full,” Yam answered. “This is why they stopped making my series. We lasted too long.”

“Yes, but,” said the boy – Hume, as he supposed he was, “I meant—”

“We must get out of this piece of wood,” said Yam. “If the reptile is alive, we have come to the wrong time and we must try again.”

Hume thought that was a good idea. He did not want to be anywhere near that scaly thing with the mouth. Yam swivelled himself around on the spot and began to stride back along the path. Hume trotted to keep up. “What have we got to try?” he asked.

“Another path,” said Yam.

“And why are we together?” Hume asked, trying again to understand. “Do we know one another? Do I belong to you or something?”

“Strictly speaking, robots are owned by humans,” Yam said. “These are hard questions to answer. You never paid for me, but I am not programmed to leave you alone. My understanding is that you need help.”

Hume trotted past a whole thicket of the airy pink blossoms, which reflected giddily all over Yam’s body. He tried again. “We know one another? You’ve met me before?”

“Many times,” said Yam.

This was encouraging. Even more encouraging, the path forked beyond the pink trees. Yam stopped with a suddenness that made Hume overshoot. He looked back to see Yam pointing a silver finger down the left fork. “This wood,” Yam told him, “is like human memory. It does not need to take events in their correct order. Do you wish to go to an earlier time and start from there?”

“Would I understand more if I did?” Hume asked.

“You might,” said Yam. “Both of us might.”

“Then it’s worth a try,” Hume agreed.

They went together down the left-hand fork.