Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

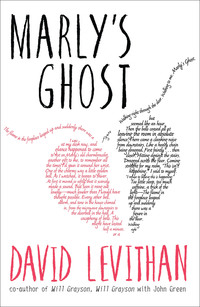

Czytaj książkę: «Marly's Ghost»

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Electric Monkey,

an imprint of Egmont UK Limited

The Yellow Building, 1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Published by arrangement with Dial,

a division of Penguin Young Readers Group,

a member of Penguin Group USA (LLC)

Text copyright © 2006 David Levithan

Illustrations © 2006 Brian Selznick

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978 1 4052 7647 4

eISBN 978 1 7803 1690 1

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Typeset by Avon DataSet Ltd, Bidford on Avon, Warwickshire

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

FOR BS & DS

(constant inspirations)

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

STAVE I

MARLY’S GHOST

STAVE II

THE FIRST OF THE THREE SPIRITS

STAVE III

THE SECOND OF THE THREE SPIRITS

STAVE IV

THE LAST OF THE SPIRITS

STAVE V

THE END OF IT AND THE BEGINNING OF IT

The Author and Illustrator would like to Acknowledge ...

Author’s Note

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Back series promotional page

STAVE I

MARLY’S GHOST

MARLY WAS DEAD, TO BEGIN WITH. There was no doubt whatsoever about that. I had been there. When she went off the treatments, she decided she wanted to die at home, and she wanted me to be there with her family. So I sat, and I waited, and I was destroyed.

There are no metaphors, no words for such a feeling. You are left with no doubt, and endless doubt.

We stood around the bed, counting her breaths, holding our own. Her father held her hand. Her mother sobbed. Her grandmothers prayed. I felt as if I was being undone one stitch at a time. She was sixteen years old, but there in the bed she could have been ninety. Everything about her that had once smiled was now gone. She hadn’t been awake for days. The last word I’d said to her was goodbye – but I’d meant for the afternoon, not forever. Afterwards, I told her I love you so many times it hurt. But I had no way of knowing whether she heard or not.

I repeated it now – I love you. I love you. Please. I love you . Then it came – that one small gasp. We waited for the next one, but there was no next one. You expect death to bring some new form of punctuation, but there it is: one small gasp. Period.

I know people say that when you die, your life flashes in front of your eyes. I have no idea what Marly saw. I will never know. But after that last gasp, after that loud silent moment, suddenly our life together flashed before my own eyes. It couldn’t have taken longer than ten seconds, but it was all there: our eighth-grade dance, the first time we’d gone out as a couple, doing the box-step in a gymnasium decorated with purple and blue balloons; watching movies together in her den, curling up together under the blanket her aunt had made when Marly was born; meeting at our new high-school lockers, passing notes, sharing books, or simply smiling at the sight of each other; going on double dates with Fred and Sarah, holding hands underneath the table, feeling her charm bracelet press against my wrist; the two of us retreating to the dark of my room, her hand rising under my shirt, my whole life bending over to kiss her; feeling her becoming lighter in my arms as the treatments took more and more and more of her.

It passed so quickly. And when it was gone – when all of it was gone – I was left with nothing. It was as if all the moments had died along with her. Everything had died. Everything except me. And that was arguable. There were times when I felt I had died, too.

When you die, the heart just stops.

When she died, my heart just stopped.

I knew she was dead. In every hour, every minute, every second since that one small gasp, I knew she was dead. How could it be otherwise?

I had known Marly for six years, since we were ten. We had been together for three of those years, until she died, just four months ago.

Her absence was all that mattered to me now, just as her presence had been all that mattered to me then. The people around me measured their days in hours or class periods or meals. I used to measure the days in glimpses of her face, touches from her hand, words sent back and forth through the air, all the things I’d tell her. I had never before experienced a love so elemental. And I never would again.

B&M

We had carved it everywhere. The trees where we walked. The benches where we sat. On the bedposts. The walls. Still there, every time I looked. There was no way to erase her without removing myself.

I was what remained. And that’s what my life felt like: remaining. I went through the motions. I drowned myself in homework and tests. I pushed myself as fast as I could through each day. I tried not to look too closely at anyone else, because they had what I’d lost – seeing them touch, seeing them happy made me bitter, jealous, sad. I was old at a young age – I knew things that nobody around me knew. I knew the truth of grief, the truth of watching a person slowly die, the angry emptiness of still being around. I made myself hard and sharp. I became secret and self-contained. Solitary.

This was not a choice. It was what I had to do.

The cold within me froze my features, made my eyes red, my thin lips blue, and spoke out in a voice that grated in my own ears. I iced the air wherever I went. I chilled all the conversations.

Love was to blame for this. Because when love ends, the cold is what you’re left with.

It was all I needed to feel.

Life goes on. Get over it. You’re still young. It’ll get better. Blah blah blah . At first people had tried to draw me in and draw me out. My friends tried to make me return to a world where there were colors besides black and gray, gave me consolations and invitations and conversations that grew more and more one-sided as my side shut down. There was no way to explain to them how I felt, because if they’d been able to understand, there wouldn’t have been any need to explain. I knew some of them loved her – genuinely loved her. But not in the way I had. I knew they were grieving, too, but I needed distance for my own grief. I chose to edge my way along the crowded paths of life, keeping sympathy away. I didn’t want it. I didn’t need it. I wanted and needed Marly, and she was gone.

I wanted to die.

That Friday, that day before Valentine’s Day, was no different. I walked through the hallways of our school and paid as little attention as I could to the stamping and wheezing and talking around me. Some lockers were decked out with construction-paper hearts – to me, the only thing they had in common with real hearts was their ability to be torn so easily. Black hearts – I wanted to see black hearts in the halls, hearts that smelled like smoke and weighed as much as sadness. While everyone else focused on their boyfriends and girlfriends, on roses and carnations and dates, I looked out the windows at the bleak midwinter. The last bell of the day had just rung, but it was quite dark already, with a fog covering the parking lot and the football field and the town beyond. I wanted to be out there, evaporating.

But I couldn’t disappear if people kept finding me. I couldn’t make it through the halls without being stopped by some bright-colored remnant of my past life.

“Happy almost-Valentine’s Day!” my onetime best friend Fred called out, coming upon me so quickly that I had no chance to avoid him. Hope still flickered in his voice – I couldn’t figure out a way to extinguish it. I was not in the mood for him, or the ghost of our friendship, or talk about Valentine’s Day and love.

“Love is humbug,” I said to him.

He was all in a glow, his eyes sparkling.

“‘Love is humbug’!” he repeated. “You can’t possibly mean that.”

He wanted me to play along, to banter. But I couldn’t do that anymore. I’d lost that.

After somebody dies, you find that everybody else’s old roles amplify. Fred had always been the one to keep us together, to rally us and cheer us. I knew he missed Marly, and I knew that somewhere underneath his gestures of happiness, he was sad. But my role had simply been to love her, and now that amplified itself in clear, lucid pain. No holiday, no talk of love, could change that.

“I do mean it,” I said, unable to keep the frost from my voice. Then, seeing he still didn’t believe me, I added, “I’m sick and tired of all this useless energy spent on love. All the drama. All the expectation. All these couples pretending to fit together because that’s what they think they’re supposed to do. I am sick of celebrating that. I am sick of glorifying the vulnerability and codependency of dimwitted lonely people who spend thirty dollars on a dozen roses and think that means something more than a waste of money.”

“Come on, Ben.” Fred looked at me with sad sympathy. The exact wrong thing to do. “You have to lighten up a little.”

“How can I lighten up,” I said darkly, “when everyone around me is so deluded? Everyone thinks that what they’re experiencing is real. That it will last. What’s Valentine’s Day about except the desperate search to find someone to spend Valentine’s Day with? It just shows that love has become a marketing campaign, like everything else. You buy into it and lose everything. If I had my way, I would force everyone who sings out ‘Happy Valentine’s Day’ to eat a thousand candy hearts without water, and then lock them in a heart-shaped box until they came out sane.”

“Ben!” Fred pleaded.

“Fred!” I returned sarcastically. “Go do Valentine’s Day your way and I’ll do it mine.”

“I don’t care about the holiday,” Fred said. “I care about you. You’re making it sound like you’ve abandoned the whole concept of love.”

“Let me abandon it, then. Love and I once had a great relationship, but I fear we’ve broken up. It cheated on me, wrecked my heart, and then went on to date other people. A lot of other people. And I can’t stand to watch it, since love’s going to cheat on them too. Just watch.”

Fred put his hand on my shoulder and it took every ounce of my restraint not to shrink away from his touch.

“I know it’s hard,” he began. And I couldn’t let him go on. This time I pulled away. Even when he tried to keep the hand there, tried to keep hold.

“If you don’t shut up,” I warned, “I’m leaving. Save the love talk for when Hallmark needs your advice.”

Stop it, Marly said, somewhere in my head. He’s your friend .

Fred’s hand dropped to his side. “Don’t be angry, Ben. I didn’t mean anything. It’s just – at least tell me you’ll come over tomorrow for the party. We really want you there.”

A party. Another place she wouldn’t be. Another place for me to sit and watch, remaining. A party I would chill to its core.

Fred and Sarah laughing. Exchanging gifts. Holding hands.

The continuing half of the double date.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “The last place I want to be is a Valentine’s gathering with you and Sarah.”

“It’s an anti-Valentine party. There will be other people there.”

“And Sarah,” I said, speaking her name like a curse. Not because I disliked her, but because I disliked them .

“What do you have against Sarah?” Fred asked.

I sighed. There was no use going into it, because it was so twisted. Every time I saw them together, I was angry at them for being together. And at the same time, I pictured how broken he’d be when it was over. How thoroughly shot.

“Why did you start going out with her?” I asked. “Because I fell in love.”

“Because you fell in love!” I laughed. “How easy for you!”

I hit the mark, and stopped Fred for a second. Then he collected himself and said, “It’s not Sarah that’s keeping you away. You haven’t hung out with me or anyone else, really, since . . .”

He wouldn’t finish the sentence, letting the last words hang in the haunted realm of the unsaid.

“Since what?” I asked cruelly.

“You know what, Ben . . . Why can’t we be friends?”

“I have to go,” I said. And it was the truth – it was as if I would slip off the edge entirely if I had to stay for one more sentence, one more attempt.

But not Fred. He always had to leave on good terms.

“I’m sorry, with all my heart, to see you like this,” he told me. “I swear to God, if I knew how to make you snap out of it, I would. Do you really think this is what she would have wanted? Do you really think this is the right way to go? You don’t even fight with me. You can’t even be bothered to do that. You think if you keep turning us down and turning us away that we’ll give up. And maybe you’re right. Maybe that’s what some people have done, and others will do. But I’m not going to stop caring about you, my friend. I’m not going to stop believing in love because of what happened. I can’t. And you shouldn’t either.”

I should have been a little moved. I should have thawed just a little bit.

But I could feel myself missing her even more. I could see her there at the party, joking with Sarah about the appropriate anti-Valentine decorations, telling Fred he looked charming in whatever he chose to wear. I could feel her warmth on the couch next to me. I could see her telling me she didn’t want a drink, then spending the night sipping from mine. I could hear her laugh. For last year’s anti-Valentine’s Day party, she’d dressed up as a beekeeper because she’d discovered that, besides being the patron saint of love and lovers, Saint Valentine was also a patron saint of beekeepers, epilepsy, fainting, and plague.

“Beekeeper,” she’d said, “seemed like the best option.”

She had lost a lot of her energy by then, so we propped her up on garish cupid pillows and acted out the story of Saint Valentine (quickly researched on the Internet) for her. If she was the beekeeper, we were all her willing hive. We showed Saint Valentine healing the blind, counseling the imprisoned until Claudius II (played with relish by Sarah) ordered him to renounce his faith. We ended with him being beaten not by clubs but by leftover candy canes, and staged his beheading using a marsh- mallow Peep.

I remembered how Marly had laughed, with me (out of the play early after playing the no-longer-blind girl) at her side. And then the laugh dissolved in the present. And the drink that I wanted to offer her in the future went untouched. And the warmth turned back to cold. I could not thaw, not even for Fred.

I looked him in the eye with all the sad and bitter coldness I felt, and I said it again: “I have to go.”

If I were in his place, I would have given up on me. But instead he left without an angry word.

I felt certain that he’d be thankful, later on, that I’d let him go.

I thought I would be free to leave now. The Valentine’s Day buzz was enclosing me more and more in a brooding claustrophobia. I had suffered through one conversation, and that had been more than enough. Marly and I used to play this game together – we called it dodgehall, and it involved running to our lockers after school, getting the books we needed, and getting out of the building before anyone else could stop us from having our time alone together. Because as much as we liked our friends, the minute our day turned from school to free time we wanted to spend that freedom on each other. All the other conversations were side conversations. All the other encounters were obstacles. We would race, and our hearts would skip, and whoever dodged through the halls the slowest would have to buy the ice cream, or finish the homework, or be the one to invent the lie we’d tell our parents when we got home late.

Of course, everything changed when she got sick. The obstacles were ones we couldn’t run past. We just had to arrange our lives around them. So we did.

I thought I could escape the school without being stopped again. But when I was at my locker, unloading my books, I was accosted by two boys with two armloads of flowers. They were both freshmen, and I only knew their names because our school didn’t have that many pairs of freshmen boyfriends. One was short and hesitant, the other tall, lanky, and hesitant.

“Would you like to buy a carnation?” Tiny asked meekly.

“The proceeds go to Key Club,” Tim quietly chimed in.

“I’m allergic,” I told them flatly.

“You could give one to your girlfriend,” Tiny offered.

“Or your boyfriend,” Tim said even more quietly.

“My girlfriend died four months ago,” I replied curtly. “And I don’t have a boyfriend.”

“I’m sorry,” Tiny said.

“That’s awful,” Tim seconded.

“You have no idea,” I said, standing now and facing them. I did not appreciate their invasion of my space. I fell out of the hold of whatever had been keeping me from lashing out. I was as tall as Tim, so much taller than Tiny. They wilted a little as I spoke. “You have no idea about anything, do you? How long have you been together?”

“Two months,” Tiny answered.

“And four days,” Tim added.

“Let me tell you right now – that’s nothing . You could plant fields of carnations for each other, and that won’t prevent what’s going to happen. You think you’re in love? You think it’s even possible for you to be in love? I’m going to tell you something, for your own good. Then you can decide whether or not to give me a flower in return. There is no such thing as ‘in love.’ Love is not something you can ever get inside of. You might think you’re there. Sure. But then you hit the border and realize you’ve been outside the whole time.”

I looked at Tiny and pointed to Tim. “I don’t know how it will end,” I told Tiny. “Maybe he’ll find someone more attractive than you. He’ll cheat on you. He’ll lie to you. He’ll swear that it’s love.” I looked at Tim and pointed to Tiny. “And maybe he’ll leave you in a different way. He’ll grow distant. He’ll become a mystery you can’t solve. Or maybe something else will intervene. He’ll need you more than you can bear. It will be too much, and because it’s too much you’ll know that you never really made it in love. You couldn’t push far enough to be in .”

They just stood there for a second, shocked. Then Tim, mumbling down to his flowers, said, “White is for friendship, pink is for crushes, and red is for love. Which do you want?”

“I want this all to be over – is that really so hard to understand? I don’t want to have anything to do with anyone. As far as I’m concerned, nobody else exists!”

“Sorry,” Tiny said, wiping his eyes. Then, seeing that it would be useless to pursue their point, he leaned into Tim and they both moved away.

The fog and the darkness outside thickened. But when I stepped into it, I couldn’t disappear completely. I could still see the things immediately around me – buses the color of caution lights, smokers on the front steps cupping their hands for fire. It was only the distance that was blotted out. Not my footsteps. Not my clouded breathing. Not my thoughts.

What did it feel like to touch her skin? What was our biggest fight? What were the exact words she said when she told me she’d go out with me? What else will I forget?

Marly, in my mind, said, Stop it.

But if I stop it, it’s over, I argued. I knew she wouldn’t want it to be over.

The church tower was invisible now, but it still rang out in the clouds, once every fifteen minutes. I felt the vibrations of time as I walked on, the railings of the graveyard now beside me. I kept walking, even though Marly was there. Her resting place, because it contained the rest of her, her remains. The things I loved were gone, and no coffin, no marker could preserve them.

Foggier yet, and colder. Piercing, searching, biting cold.

Picturing her crying. Feeling her tears soak into her shirt. Knowing there was nothing, nothing that I could do.

Having her scream at me – Go away . Having her tell me she was all alone, that there was no way for me to understand how that felt. Telling me to leave, but letting me back in after a phone call, a note, a day passing.

I plunged past, into town. A loving couple loitered across the sidewalk in front of me, holding hands, nestling against the cold. I had to run into the street to get around them. I wanted to yell.

Her voice in my head: There should be a minimum speed limit for people in love walking on the sidewalk. They’re worse than moms with strollers . Or maybe just my own voice in my head, disguised as hers.

I passed the park with the playground swings and the diner with the jukebox booths. The trees we’d vowed to climb and the benches where we would sit reading next to each other, her arm pressed so closely against mine that I’d feel it when she turned a page. All of the places that had been bled of purpose. I couldn’t feel anything for them anymore, except loss. The past was ruined for me.

My parents were away for the weekend, so I stopped at a quiet, forlorn deli far enough into the outskirts of our small suburban town to be private. I sat at one of the two tables and single-mindedly plied through my homework and ate food without taste. The light was fluorescent. No music played. That was all right with me.

When I was done there, I took a shortcut through a thick veil of trees to get to my house. Closer to the center of town, the houses kept one another company, the doorways only a conversational distance apart. Here, however, the houses kept to themselves. Ours was an old and dreary recluse – I hadn’t even liked it as a kid. Even though I knew every step of the shortcut, every step of the yard, I found myself groping through the darkness that had set in, so full of frost and fog. I made it up the front steps and had just put my key in the lock when I stopped and looked at the old knocker on the door.

There was nothing at all particular about the knocker, except that it was very large. It had been on the door for as long as we’d lived in the house, which in my case was as long as I’d been alive. I had walked past the knocker for years without seeing it, or caring if it saw me. But this time something made me stop. Something made me look. One moment it was just the ordinary knocker. And the next moment it was . . .

Marly’s face.

It was not in impenetrable shadow, as the other objects in the yard were, but had a dismal light around it, like the lowest flame on a gas range. It wasn’t angry or ferocious, but looked exactly like she used to look when she’d stop in the middle of studying to talk to me, her glasses turned up on her forehead. Her hair was stirred, as if by breath or hot air, and though her eyes were wide open, they didn’t move. That, and the shock of seeing the startling blue of her eyes again, made it horrible. But the horror seemed to be on my side, not hers.

Before I could even gasp, she was gone.

I’d seen her before, of course. I saw her all the time. Looking out the window in class, I would see her walking across the front lawn, and I would want to jump out of my seat and pound on the glass to call for her. Then she’d come a little closer and it wouldn’t be her at all. Just another blond girl on her way to school. A stranger.

Or I’d imagine her. Close my eyes and run the memories of us. See her laughing next to me on my bed. See her pointing out my mismatched socks, amused. Catch her face out of the many in the hallway, see her smile connect as she found me finding her. All these memories were silent. But often that was enough. I would talk back to her, even if I couldn’t hear what she was saying.

I tried to convince myself that this was just another one of those sightings. Those imaginings. That fiction.

But still, I did pause before I shut the door. And I did look cautiously behind it first, as if I half expected to find her there, waiting for me. But there was nothing on the back of the door but the screws and nuts that held the knocker in place. I told myself to get a grip and closed the door with a bang.

The sound resounded through the house like thunder. Every room, from attic to basement, seemed to have its own peal of echoes.

I convinced myself this was normal. Nothing to be afraid of.

I didn’t turn on any lights as I walked upstairs to my room. Darkness was solitary, and I liked it. During that brief flicker of her face, I had felt I wasn’t alone. I needed the darkness to erase that feeling. Because it was a feeling, and I preferred not to feel.

Still, the presence nagged at me. Like a complete fool, I checked under my bed when I got to my room, then opened my closet and took a quick peek between the hanging clothes. Nothing was out of the ordinary. I saw her jacket hanging there and instinctively reached out to touch it – the yellow tattered jacket she’d wanted me to keep, knowing I’d have no use for it except as something to remember her by.

I walked over to the fireplace in my room, which my parents only let me use on cold nights. I checked that the flue was open, then lit the log. A low fire began to burn.

There had been one night, not that long ago, when the memories of Marly had been too much. I had grabbed the tattered shoebox containing our notes and letters, determined to do some harm. I took the top letter and touched it to the flame. I watched it burn for about five seconds before I realized what I was doing and desperately tried to stop it. Too late.

The fireplace was an old one, paved all around with tiles. Blank white tiles . . . which now, as I watched, began to be scribbled with words. Marly’s handwriting. The letter I had burned, returned to me now, scrawled across the porcelain.

“No!” I gasped, blinking hard and pulling away. A thousand justifications volunteered themselves in my mind – too little sleep, too much caffeine, a trick of the light. But my fear only grew.

From the other side of the room, it looked like the writing had faded away. I was at my desk now, and my glance happened to come to rest on Marly’s old charm bracelet, another last gift to me, to remember all the times I’d spun it around her wrist. One of the charms was a little golden bell. As I watched, it began to shiver. At first it moved so softly that it scarcely made a sound. But soon it rang out loudly – much louder than I would have thought possible. Every other bell, alarm, and tone in the house chimed in, from the microwave downstairs to the doorbell in the hall. A cacophony of bells.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.