Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «The Golden Keel»

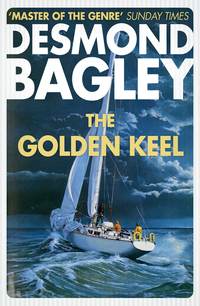

DESMOND BAGLEY

The Golden Keel

COPYRIGHT

HARPER

an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1963

Copyright © Brockhurst Publications 1963

Desmond Bagley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008211134

Ebook Edition © January 2016 ISBN 9780008211417

Version: 2016-11-21

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

The Golden Keel

Dedication

Book One: The Men

Chapter One: Walker

Chapter Two: Coertze

Book Two: The Gold

Chapter Three: Tangier

Chapter Four: Francesca

Chapter Five: The Tunnel

Chapter Six: Metcalfe

Chapter Seven: The Golden Keel

Book Three: The Sea

Chapter Eight: Calm and Storm

Chapter Nine: Sanford

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

THE GOLDEN KEEL

DEDICATION

For Joan – who else?

BOOK ONE The Men

ONE: WALKER

My name is Peter Halloran, but everyone calls me ‘Hal’ excepting my wife, Jean, who always called me Peter. Women seem to dislike nicknames for their menfolk. Like a lot of others I emigrated to the ‘colonies’ after the war, and I travelled from England to South Africa by road, across the Sahara and through the Congo. It was a pretty rough trip, but that’s another story; it’s enough to say that I arrived in Cape Town in 1948 with no job and precious little money.

During my first week in Cape Town I answered several of the Sit. Vac. advertisements which appeared in the Cape Times and while waiting for answers I explored my environment. On this particular morning I had visited the docks and finally found myself near the yacht basin.

I was leaning over the rail looking at the boats when a voice behind me said, ‘If you had your choice, which would it be?’

I turned and encountered the twinkling eyes of an elderly man, tall, with stooped shoulders and grey hair. He had a brown, weather-beaten face and gnarled hands, and I estimated his age at about sixty.

I pointed to one of the boats. ‘I think I’d pick that one,’ I said. ‘She’s big enough to be of use, but not too big for single-handed sailing.’

He seemed pleased. ‘That’s Gracia,’ he said. ‘I built her.’

‘She looks a good boat,’ I said. ‘She’s got nice lines.’

We talked for a while about boats. He said that he had a boatyard a little way outside Cape Town towards Milnerton, and that he specialized in building the fishing boats used by the Malay fishermen. I’d noticed these already; sturdy unlovely craft with high bows and a wheelhouse stuck on top like a chicken-coop, but they looked very seaworthy. Gracia was only the second yacht he had built.

‘There’ll be a boom now the war’s over,’ he predicted. ‘People will have money in their pockets, and they’ll go in for yachting. I’d like to expand my activities in that direction.’

Presently he looked at his watch and nodded towards the yacht club. ‘Let’s go in and have a coffee,’ he suggested.

I hesitated. ‘I’m not a member.’

‘I am,’ he said. ‘Be my guest.’

So we went into the club house and sat in the lounge overlooking the yacht basin and he ordered coffee. ‘By the way, my name’s Tom Sanford.’

‘I’m Peter Halloran.’

‘You’re English,’ he said. ‘Been out here long?’

I smiled. ‘Three days.’

‘I’ve been out just a bit longer – since 1910.’ He sipped his coffee and regarded me thoughtfully. ‘You seem to know a bit about boats.’

‘I’ve been around them all my life,’ I said. ‘My father had a boatyard on the east coast, quite close to Hull. We built fishing boats, too, until the war.’

‘And then?’

‘Then the yard went on to contract work for the Admiralty,’ I said. ‘We built harbour defence launches and things like that – we weren’t geared to handle anything bigger.’ I shrugged. ‘Then there was an air-raid.’

‘That’s bad,’ said Tom. ‘Was everything destroyed?’

‘Everything,’ I said flatly. ‘My people had a house next to the yard – that went, too. My parents and my elder brother were killed.’

‘Christ!’ said Tom gently. ‘That’s very bad. How old were you?’

‘Seventeen,’ I said. ‘I went to live with an aunt in Hatfield; that’s when I started to work for de Havilland – building Mosquitos. It’s a wooden aeroplane and they wanted people who could work in wood. All I was doing, as far as I was concerned, was filling in time until I could join the Army.’

His interest sharpened. ‘You know, that’s the coming thing – the new methods developed by de Havilland. That hot-moulding process of theirs – d’you think it could be used in boat-building?’

I thought about it. ‘I don’t see why not – it’s very strong. We did repair work at Hatfield, as well as new construction, and I saw what happens to that type of fabric when it’s been hit very hard. It would be more expensive than the traditional methods, though, unless you were mass-producing.’

‘I was thinking about yachts,’ said Tom slowly. ‘You must tell me more about it sometime.’ He smiled. ‘What else do you know about boats?’

I grinned. ‘I once thought I’d like to be a designer,’ I said. ‘When I was a kid – about fifteen – I designed and built my own racing dinghy.’

‘Win any races?’

‘My brother and I had ’em all licked,’ I said. ‘She was a fast boat. After the war, when I was cooling my heels waiting for my discharge, I had another go at it – designing, I mean. I designed half a dozen boats – it helped to pass the time.’

‘Got the drawings with you?’

‘They’re somewhere at the bottom of my trunk,’ I said. ‘I haven’t looked at them for a long time.’

‘I’d like to see them,’ said Tom. ‘Look, laddie; how would you like to work for me? I told you I’m thinking of expanding into the yacht business, and I could use a smart young fellow.’

And that’s how I started working for Tom Sanford. The following day I went to the boatyard with my drawings and showed them to Tom. On the whole he liked them, but pointed out several ways in which economies could be made in the building. ‘You’re a fair designer,’ he said. ‘But you’ve a lot to learn about the practical side. Never mind, we’ll see about that. When can you start?’

Going to work for old Tom was one of the best things I ever did in my life.

II

A lot of things happened in the next ten years – whether I deserved them or not is another matter. The skills I had learned from my father had not deserted me, and although I was a bit rusty to begin with, soon I was as good as any man in the yard, and maybe a bit better. Tom encouraged me to design, ruthlessly correcting my errors.

‘You’ve got a good eye for line,’ he said. ‘Your boats would be sweet sailers, but they’d be damned expensive. You’ve got to spend more time on detail; you must cut down costs to make an economical boat.’

Four years after I joined the firm Tom made me yard foreman, and just after that, I had my first bit of luck in designing. I submitted a design to a local yachting magazine, winning second prize and fifty pounds. But better still, a local yachtsman liked the design and wanted a boat built. So Tom built it for him and I got the designer’s fee which went to swell my growing bank balance.

Tom was pleased about that and asked if I could design a class boat as a standard line for the yard, so I designed a six-tonner which turned out very well. We called it the Penguin Class and Tom built and sold a dozen in the first year at £2000 each. I liked the boat so much that I asked Tom if he would build one for me, which he did, charging a rock-bottom price and letting me pay it off over a couple of years.

Having a design office gave the business a fillip. The news got around and people started to come to me instead of using British and American designs. That way they could argue with their designer. Tom was pleased because most of the boats to my design were built in the yard.

In 1954 he made me yard manager, and in 1955 offered me a partnership.

‘I’ve got no one to leave it to,’ he said bluntly. ‘My wife’s dead and I’ve got no sons. And I’m getting old.’

I said, ‘You’ll be building boats when you’re a hundred, Tom.’

He shook his head. ‘No, I’m beginning to feel it now.’ He wrinkled his brow. ‘I’ve been going over the books and I find that you’re bringing more business into the firm than I am, so I’ll go easy on the money for the partnership. It’ll cost you five thousand pounds.’

Five thousand was ridiculously cheap for a half-share in such a flourishing business, but I hadn’t got anywhere near that amount. He saw my expression and his eyes crinkled. ‘I know you haven’t got it – but you’ve been doing pretty well on the design side lately. My guess is that you’ve got about two thousand salted away.’

Tom, shrewd as always, was right. I had a couple of hundred over the two thousand. ‘That’s about it,’ I said.

‘All right. Throw in the two thousand and borrow another three from the bank. They’ll lend it to you when they see the books. You’ll be able to pay it back out of profits in under three years, especially if you carry out your plans for that racing dinghy. What about it?’

‘O.K., Tom,’ I said. ‘It’s a deal.’

The racing dinghy Tom had mentioned was an idea I had got by watching the do-it-yourself developments in England. There are plenty of little lakes on the South African highveld and I thought I could sell small boats away from the sea if I could produce them cheaply enough – and I would sell either the finished boat or a do-it-yourself kit for the impoverished enthusiast.

We set up another woodworking shop and I designed the boat which was the first of the Falcon Class. A young fellow, Harry Marshall, was promoted to run the project and he did very well. This wasn’t Tom’s cup of tea and he stayed clear of the whole affair, referring to it as ‘that confounded factory of yours’. But it made us a lot of money.

It was about this time that I met Jean and we got married. My marriage to Jean is not really a part of this story and I wouldn’t mention it except for what happened later. We were very happy and very much in love. The business was doing well – I had a wife and a home – what more could a man wish for?

Towards the end of 1956 Tom died quite suddenly of a heart attack. I think he must have known that his heart wasn’t in good shape although he didn’t mention it to anyone. He left his share of the business to his wife’s sister. She knew nothing about business and less about boat-building, so we got the lawyers on to it and she agreed to sell me her share. I paid a damn sight more than the five thousand I had paid Tom, but it was a fair sale although it gave me financier’s fright and left me heavily in debt to the bank.

I was sorry that Tom had gone. He had given me a chance that fell to few young fellows and I felt grateful. The yard seemed emptier without him pottering about the slips.

The yard prospered and it seemed that my reputation as a designer was firm, because I got lots of commissions. Jean took over the management of the office, and as I was tied to the drawing board for a large proportion of my time I promoted Harry Marshall to yard manager and he handled it very capably.

Jean, being a woman, gave the office a thorough spring cleaning as soon as she was in command, and one day she unearthed an old tin box which had stayed forgotten on a remote shelf for years. She delved into it, then said suddenly, ‘Why have you kept this clipping?’

‘What clipping?’ I asked abstractedly. I was reading a letter which could lead to an interesting commission.

‘This thing about Mussolini,’ she said. ‘I’ll read it.’ She sat on the edge of the desk, the yellowed fragment of newsprint between her fingers. ‘“Sixteen Italian Communists were sentenced in Milan yesterday for complicity in the disappearance of Mussolini’s treasure. The treasure, which mysteriously vanished at the end of the war, consisted of a consignment of gold from the Italian State Bank and many of Mussolini’s personal possessions, including the Ethiopian crown. It is believed that a large number of important State documents were with the treasure. The sixteen men all declared their innocence.”’

She looked up. ‘What was all that about?’

I was startled. It was a long time since I’d thought of Walker and Coertze and the drama that had been played out in Italy. I smiled and said, ‘I might have made a fortune but for that news story.’

‘Tell me about it?’

‘It’s a long story,’ I protested. ‘I’ll tell you some other time.’

‘No,’ she insisted. ‘Tell me now; I’m always interested in treasure.’

So I pushed the unopened mail aside and told her about Walker and his mad scheme. It came back to me hazily in bits and pieces. Was it Donato or Alberto who had fallen – or been pushed – from the cliff? The story took a long time in the telling and the office work got badly behind that day.

III

I met Walker when I had arrived in South Africa from England after the war. I had been lucky to get a good job with Tom but, being a stranger, I was a bit lonely, so I joined a Cape Town Sporting Club which would provide company and exercise.

Walker was a drinking member, one of those crafty people who joined the club to have somewhere to drink when the pubs were closed on Sunday. He was never in the club house during the week, but turned up every Sunday, played his one game of tennis for the sake of appearances, then spent the rest of the day in the bar.

It was in the bar that I met him, late one Sunday afternoon. The room was loud with voices raised in argument and I soon realized I had walked into the middle of a discussion on the Tobruk surrender. The very mention of Tobruk can start an argument anywhere in South Africa because the surrender is regarded as a national disgrace. It is always agreed that the South Africans were let down but from then on it gets heated and rather vague. Sometimes the British generals are blamed and sometimes the South African garrison commander, General Klopper; and it’s always good for one of those long, futile bar-room brawls in which tempers are lost but nothing is ever decided.

It wasn’t of much interest to me – my army service was in Europe – so I sat quietly nursing my beer and keeping out of it. Next to me was a thin-faced young man with dissipated good looks who had a great deal to say about it, with many a thump on the counter with his clenched fist. I had seen him before but didn’t know who he was. All I knew of him was by observation; he seemed to drink a lot, and even now was drinking two brandies to my one beer.

At length the argument died a natural death as the bar emptied and soon my companion and I were the last ones left. I drained my glass and was turning to leave when he said contemptuously, ‘Fat lot they know about it.’

‘Were you there?’ I asked.

‘I was,’ he said grimly. ‘I was in the bag with all the others. Didn’t stay there long, though; I got out of the camp in Italy in ’43.’ He looked at my empty glass. ‘Have one for the road.’

I had nothing to do just then, so I said, ‘Thanks; I’ll have a beer.’

He ordered a beer for me and another brandy for himself and said, ‘My name’s Walker. Yes, I got out when the Italian Government collapsed. I joined the partisans.’

‘That must have been interesting,’ I said.

He laughed shortly. ‘I suppose you could call it that. Interesting and scary. Yes, I reckon you could say that me and Sergeant Coertze had a really interesting time – he was a bloke I was with most of the time.’

‘An Afrikaner?’ I hazarded. I was new in South Africa and didn’t know much about the set-up then, but the name sounded as though it might be Afrikaans.

‘That’s right,’ said Walker. ‘A real tough boy, he was. We stuck together after getting out of the camp.’

‘Was it easy – escaping from the prison camp?’

‘A piece of cake,’ said Walker. ‘The guards co-operated with us. A couple of them even came with us as guides – Alberto Corso and Donato Rinaldi. I liked Donato – I reckon he saved my life.’

He saw my interest and plunged into the story with gusto. When the Government fell in 1943 Italy was in a mess. The Italians were uneasy; they didn’t know what was going to happen next and they were suspicious of the intentions of the Germans. It was a perfect opportunity to break camp, especially when a couple of the guards threw in with them.

Leaving the camp was easy enough, but trouble started soon after when the Germans laid on an operation to round up all the Allied prisoners who were loose in Central Italy.

‘That’s when I copped it,’ said Walker. ‘We were crossing a river at the time.’

The sudden attack had taken them by surprise. Everything had been silent except for the chuckling of the water and the muffled curses as someone slipped – then suddenly there was the sound of ripped calico as the Spandau opened up and the night was made hideous by the eerie whine of bullets as they ricocheted from exposed rocks in the river.

The two Italians turned and let go with their sub-machine-guns. Coertze, bellowing like a bull, scrabbled frantically at the pouch pocket of his battle-dress trousers and then his arm came up in an overarm throw. There was a sharp crack as the hand grenade exploded in the water near the bank. Again Coertze threw and this time the grenade burst on the bank.

Walker felt something slam his leg and he turned in a twisting fall and found himself gasping in the water. His free arm thrashed out and caught on a rock and he hung on desperately.

Coertze threw another grenade and the machine-gun stopped. The Italians had emptied their magazines and were busy reloading. Everything was quiet again.

‘I reckon they thought we were Germans, too,’ said Walker. ‘They wouldn’t expect to be fired on by escaping prisoners. It was lucky that the Italians had brought some guns along. Anyway, that bloody machine-gun stopped.’

They had stayed for a few minutes in midstream with the quick cold waters pulling at their legs, not daring to move in case there was a sudden burst from the shore. After five minutes Alberto said in a low voice, ‘Signor Walker, are you all right?’

Walker pulled himself upright and to his astonishment found himself still grasping his unfired rifle. His left leg felt numb and cold. ‘I’m all right,’ he said.

There was a long sigh from Coertze, then he said, ‘Well, come on. Let’s get to the other side – but quietly.’

They reached the other side of the river and, without resting, pressed on up the mountainside. After a short time Walker’s leg began to hurt and he lagged behind. Alberto was perturbed. ‘You must hurry; we have to cross this mountain before dawn.’

Walker stifled a groan as he put down his left foot. ‘I was hit,’ he said. ‘I think I was hit.’

Coertze came back down the mountain and said irritably, ‘Magtig, get a move on, will you?’

Alberto said, ‘Is it bad, Signor Walker?’

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Coertze, not understanding the Italian.

‘I have a bullet in my leg,’ said Walker bitterly.

‘That’s all we need,’ said Coertze. In the darkness he bulked as a darker patch and Walker could see that he was shaking his head impatiently. ‘We’ve got to get to that partisan camp before daylight.’

Walker conferred with Alberto, then said in English, ‘Alberto says there’s a place along there to the right where we can hide. He says that someone should stay with me while he goes for help.’

Coertze grunted in his throat. ‘I’ll go with him,’ he said. ‘The other Eytie can stay with you. Let’s get to it.’

They moved along the mountainside and presently the ground dipped and suddenly there was a small ravine, a cleft in the mountain. There were stunted trees to give a little cover and underfoot was a dry watercourse.

Alberto stopped and said, ‘You will stay here until we come for you. Keep under the trees so that no one will see you, and make as little movement as possible.’

‘Thanks, Alberto,’ said Walker. There were a few brief words of farewell, then Alberto and Coertze disappeared into the night. Donato made Walker comfortable and they settled down to wait out the night.

It was a bad time for Walker. His leg was hurting and it was very cold. They stayed in the ravine all the next day and as night fell Walker became delirious and Donato had trouble in keeping him quiet.

When the rescuers finally came Walker had passed out. He woke up much later and found himself in a bed in a room with whitewashed walls. The sun was rising and a little girl was sitting by the bedside.

Walker stopped speaking suddenly and looked at his empty glass on the bar counter. ‘Have another drink,’ I said quickly.

He needed no encouraging so I ordered another couple of drinks. ‘So that’s how you got away,’ I said.

He nodded. ‘That’s how it was. God, it was cold those two nights on that bloody mountain. If it hadn’t been for Donato I’d have cashed in my chips.’

I said, ‘So you were safe – but where were you?’

‘In a partisan camp up in the hills. The partigiani were just getting organized then; they only really got going when the Germans began to consolidate their hold on Italy. The Jerries ran true to form – they’re arrogant bastards, you know – and the Italians didn’t like it. So everything was set for the partisans; they got the support of the people and they could begin to operate on a really large scale.

‘They weren’t all alike, of course; there was every shade of political opinion from pale blue to bright red. The Communists hated the Monarchists’ guts and vice versa and so on. The crowd I dropped in on were Monarchist. That’s where I met the Count.’

Count Ugo Montepescali di Todi was over fifty years old at that time, but young-looking and energetic. He was a swarthy man with an aquiline nose and a short greying beard which was split at the end and forked aggressively. He came of a line which was old during the Renaissance and he was an aristocrat to his fingertips.

Because of this he hated Fascism – hated the pretensions of the parvenu rulers of Italy with all their corrupt ways and their money-sticky fingers. To him Mussolini always remained a mediocre journalist who had succeeded in demagoguery and had practically imprisoned his King.

Walker met the Count the first day he arrived at the hill camp. He had just woken up and seen the solemn face of the little girl. She smiled at him and silently left the room, and a few minutes later a short stocky man with a bristling beard stepped through the doorway and said in English, ‘Ah, you are awake. You are quite safe now.’

Walker was conscious of saying something inane. ‘But where am I?’

‘Does that really matter?’ the Count asked quizzically. ‘You are still in Italy – but safe from the Tedesci. You must stay in bed until you recover your strength. You need some blood putting back – you lost a lot – so you must rest and eat and rest again.’

Walker was too weak to do more than accept this, so he lay back on the pillow. Five minutes later Coertze came in; with him was a young man with a thin face.

‘I’ve brought the quack,’ said Coertze. ‘Or at least that’s what he says he is – if I’ve got it straight. My guess is that he’s only a medical student.’

The doctor – or student – examined Walker and professed satisfaction at his condition. ‘You will walk within the week,’ he said, and packed his little kit and left the room.

Coertze rubbed the back of his head. ‘I’ll have to learn this slippery taal,’ he said. ‘It looks as though we’ll be here for a long time.’

‘No chance of getting through to the south?’ asked Walker.

‘No chance at all,’ said Coertze flatly. ‘The Count – that’s the little man with the bokbaardjie – says that the Germans down south are thicker on the ground than stalks in a mealie field. He reckons they’re going to make a defence line south of Rome.’

Walker sighed. ‘Then we’re stuck here.’

Coertze grinned. ‘It is not too bad. At least we’ll get better food than we had in camp. The Count wants us to join his little lot – it seems he has some kind of skietkommando which holds quite a bit of territory and he’s collected men and weapons while he can. We might as well fight here as with the army – I’ve always fancied fighting a war my way.’

A plump woman brought in a steaming bowl of broth for Walker, and Coertze said, ‘Get outside of that and you’ll feel better. I’m going to scout around a bit.’

Walker ate the broth and slept, then woke and ate again. After a while a small figure came in bearing a basin and rolled bandages. It was the little girl he had seen when he had first opened his eyes. He thought she was about twelve years old.

‘My father said I had to change your bandages,’ she said in a clear young voice. She spoke in English.

Walker propped himself up on his elbows and watched her as she came closer. She was neatly dressed and wore a white, starched apron. ‘Thank you,’ he said.

She bent to cut the splint loose from his leg and then she carefully loosened the bandage round the wound. He looked down at her and said, ‘What is your name?’

‘Francesca.’

‘Is your father the doctor?’ Her hands were cool and soft on his leg.

She shook her head. ‘No,’ she said briefly.

She bathed the wound in warm water containing some pungent antiseptic and then shook powder on to it. With great skill she began to rebandage the leg.

‘You are a good nurse,’ said Walker.

It was only then that she looked at him and he saw that she had cool, grey eyes. ‘I’ve had a lot of practice,’ she said, and Walker was abashed at her gaze and cursed a war which made skilled nurses out of twelve-year-olds.

She finished the bandaging and said, ‘There – you must get better soon.’

‘I will,’ promised Walker. ‘As quickly as I can. I’ll do that for you.’

She looked at him with surprise. ‘Not for me,’ she said. ‘For the war. You must get better so that you can go into the hills and kill a lot of Germans.’

She gravely collected the soiled bandages and left the room, with Walker looking after her in astonishment. Thus it was that he met Francesca, the daughter of Count Ugo Montepescali.

In a little over a week he was able to walk with the aid of a stick and to move outside the hospital hut, and Coertze showed him round the camp. Most of the men were Italians, army deserters who didn’t like the Germans. But there were many Allied escapees of different nationalities.

The Count had formed the escapees into a single unit and had put Coertze in command. They called themselves the ‘Foreign Legion’. During the next couple of years many of them were to be killed fighting against the Germans with the partisans. At Coertze’s request, Alberto and Donato were attached to the unit to act as interpreters and guides.

Coertze had a high opinion of the Count. ‘That kêrel knows what he’s doing,’ he said. ‘He’s recruiting from the Italian army as fast as he can – and each man must bring his own gun.’

When the Germans decided to stand and fortified the Winterstellung based on the Sangro and Monte Cassino, the war in Italy was deadlocked and it was then that the partisans got busy attacking the German communications. The Foreign Legion took part in this campaign, specializing in demolition work. Coertze had been a gold miner on the Witwatersrand before the war and knew how to handle dynamite. He and Harrison, a Canadian geologist, instructed the others in the use of explosives.

They blew up road and rail bridges, dynamited mountain passes, derailed trains and occasionally shot up the odd road convoy, always retreating as soon as heavy fire was returned. ‘We must not fight pitched battles,’ said the Count. ‘We must not let the Germans pin us down. We are mosquitoes irritating the German hides – let us hope we give them malaria.’

Walker found this a time of long stretches of relaxation punctuated by moments of fright. Discipline was easy and there was no army spit-and-polish. He became lean and hard and would think nothing of making a day’s march of thirty miles over the mountains burdened with his weapons and a pack of dynamite and detonators.