Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Lord Byron’s Jackal: A Life of Trelawny»

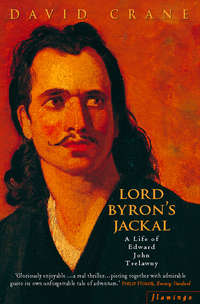

LORD BYRON’S JACKAL

THE LIFE OF

Edward John Trelawny

DAVID CRANE

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

List of Maps

Nauplia

1 The Wolf Cub

2 The Sun and the Glow-Worm

3 Et in Arcadia Ego

4 Odysseus

5 The Death of Byron

6 Parnassus

7 The Plot

8 Whitcombe

9 Assassination

10 Humphreys

11 Enter the Major

12 Shame

13 The Last of Greece

14 Going Public

15 The Keeper of the Flame

Notes to the Text

Reference Notes

Sources and Select Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

LIST OF MAPS

Greece 1823–1827

Major Francis D’Arcy Bacon’s Journey 1823–1825

NAUPLIA

‘What a queer set! What an assemblage of romantic, adventurous, restless, crack-brained young men from the four corners of the world. How much courage and talent is to be found among them; but how much more of pompous vanity, of weak intellect, of mean selfishness, of utter depravity … Little have Philhellenes done towards raising the reputation of Europeans here!’

Samuel Gridley Howe 1

ON 6 FEBRUARY 1833 a seventeen-year-old Bavarian prince entered the town of Nauplia as the first king of Modern Greece. Out in the Gulf of Argos the ships of the sponsoring powers rode at anchor in the bright spring sunshine. French, Russian and British bands serenaded each other across the water in an improbable display of amity, while from the batteries on shore salute after salute rolled across the bay in tribute to Christendom’s youngest nation.

To the pragmatist and romantic alike there can have been no more fitting place for Otho to begin his reign than here on the Argolic Gulf under the watchful gaze of Europe’s navies and Greece’s Homeric past. Nothing, it seemed, had been left to chance to guarantee his future. The civilized world had given its blessing and its money. A loan had been provided to buttress his new country through her first years, an indemnity paid to her old Ottoman masters to rescue her from her troubled past.

Inside the town Bavarian and French troops stood ready to enforce Europe’s choice on a population only too accustomed to dissent, but for the moment the precautions were unnecessary. Mountain Suliotes and island merchants, sailors and Moreot bandits, Peloponnesian peasants and Phanariot politicians waited to greet the young king as their saviour from years of war and chaos. As Otho rode on his white horse through the cheering crowds into the reconquered Turkish town, the peculiar spell of Greece, its unique hold on the nineteenth century as the cradle of Western culture and the champion of Christianity, took on a palpable form that seemed in itself a guarantee of the new order.

For a dozen years this small town on the eastern coast of the Peloponnese, some forty miles south of Corinth, had exercised the same charm over the imaginations of Europe and America. From that moment in 1821 when Bishop Germanos had raised the standard of revolt and called on Greece to throw off four centuries of Ottoman rule Nauplia had been as familiar as any city in Europe. Its news was carried in newspapers from Vienna to Boston, its victories celebrated and its defeats mourned, its dead turned into martyrs, its leaders into the heirs of Demosthenes and Leonidas on a wave of popular enthusiasm which sent money and men to fight for a cause that seemed as much Christendom’s as Greece’s. ‘No other subject has ever excited such a powerful sensation,’ one enthusiast could write long after the first flush of excitement had faded,

The very peasants throughout Switzerland and Germany inquire with anxiety, when their affairs call them to market, what are the last news … In France subscriptions have been opened, and money solicited throughout every town, on behalf of a Christian Nation doomed to perish by the sword or by famine. The Duchesses of Albey, Broglio, and De Caze; every Frenchwoman distinguished by rank, riches, talent, or virtue, have divided the different quarters of Paris among them, and traverse on foot every street, and enter into every house, demanding the charity of their inhabitants for a nation of martyrs.2

Almost every foreign volunteer swept along by this enthusiasm had passed through the town of Nauplia, many of them to stay for ever, victims of the squalor, disease and factional greed which lay behind the ceremonial glamour of Otho’s welcome. Italians, Swiss, Swedes, Scots, Irish and Poles had all come here, national rivalries if not forgotten at least subsumed into a common cause, Germans and French who had fought on opposite sides in the Napoleonic Wars, Americans and English enemies at New Orleans united under the name of ‘Philhellene’ – friend of Modern Greece, a Greece which Nauplia promised was the true heir to the land of Homer and Thucydides.

The ceremonial entry of Otho was the last great charade in Nauplia’s history, the last time that the town would work its illusions on a Europe determined to believe. That place is gone, the walls of its lower town pulled down, the surrounding marshes which once earned its pestilential reputation as the Batavia of Greece drained. Within a year of coming ashore from a British frigate, Otho had moved his capital to Athens and the port that the Venetians had called Napoli di Romania had begun its slow decline into the quaint irrelevance of modern Nauplia.

If you wander now among its steep, narrow streets, or along the waterfront with its view across to the jewel-like island fortress where nineteenth-century Nauplia, with its instinctive dislike for reality, housed its public executioner, there can seem nowhere in Greece that retains so much of its architecture and so little of its history. There is an elegance about even its fortifications that belies their past, that touch of unreality which is Venice’s supreme gift to her former possessions. Towards evening, especially, as the sun sinks behind the central mass of the Peloponnese, and the lines of Lassalle’s Palamidi citadel almost dissolve into the rock face, it is difficult to believe anything ever disturbed the town’s peace. Down in the harbour, near an obelisk commemorating French soldiers, a Hotel Grand Bretagne throws off a confused echo of the excitement of 1824 when a ship carrying English gold made Nauplia a sink for every patriot, idealist, charlatan and scrounger in Greece. In the centre of the old town, where the starving Turkish population once held out for a whole year, their mosque has been turned with an insolence too complete to be accident into a cinema. A little higher up the slope, a bullet mark still pocks the wall where Greece’s first president was assassinated. And in that bullet hole, carefully preserved behind glass, we have the quintessential Nauplia-history in aspic, sanitised and mythologized, history reduced to civic statuary and street names, the narrow alleys once notorious for their filth sunk now beneath nothing more oppressive than bougainvillaea, the extravagance, rivalries and violence of its brief years of fame no more intrusive than the wrecks of warships that lie submerged beneath the waters of the gulf.

On a July day in 1841 a group of foreigners gathered in the town’s Roman Catholic Church to add their own lie to the great historical deception that modern Nauplia enshrines. The Church of the Metamorphosis is a small domed building, perched alongside the Hotel Byron on a terrace beneath the walls of the upper town, looking out westwards across the bay towards the ruins of Argos and the Frankish citadel of Larissa. At its south east corner the foundations of an old minaret are visible, and inside the sense of space and air still feels closer to the mosque it once was than any Greek church. Above its altar, a copy of a Raphael Holy Family, the gift of Louis Philippe to King Otho, intrudes a fleshily different but no less alien note. Opposite it, framing the door in a sad parody of a triumphal arch, stands the monument that had brought the congregation to the church that day. It was the work of a Frenchman called Thouret, a ‘Lt. Colonel’ and a ‘Chevalier de Plusieurs Ordres’ he has signed himself with a gallic swagger. ‘A La Memoire Des Philhellènes’, it reads across the top, ‘Morts pour L’independance, La Grèce, Le Roi, et Leurs Compagnons D’Armes Reconnaissants.’ Down the length of its four pillars, inscribed in white on black wood, riddled with mis-spellings, are the names of almost three hundred foreign dead who in the decade before Otho’s arrival had come out to fight for Greek independence.

There can be few more forlorn memorials. Sometimes along the Dutch border one comes across a German cemetery from the last war buried deep in a wood, but even those graves with their air of furtive and collective guilt scarcely catch the sad futility that clings to Thouret’s monument. There is something about its shabby theatricality that nothing else quite matches, a sense of defeated grandeur and deluded optimism which inadvertently captures the fate of the men it commemorates. ‘Hellenes,’ it says, ‘we were and are with you.’ It is not true and it never was. Who, inside or outside Greece, has heard of a single Philhellene other than Byron? How many memorials are there raised by the Greeks themselves in their memory? How, if Greece had deliberately set out to disown their memory, could it have done better than here in Nauplia? – in a town synonymous with Philhellene disillusion, in a converted Turkish mosque given by a German King to the Roman Catholic Church? Could there be any more eloquent or insouciant tribute to the insignificance of these lives than to obliterate their identity in the crude errors and chaotic lettering of their only monument?*

Beneath its hollow rhetoric, however, is that common denominator which links its names with those on the monuments of villages, schools, hospitals or railway stations from the Falklands to Burma, from South Africa to Sevastopol. There is always a sharp poignancy in the way these memorials bring the familiar and strange into such permanent proximity, that lives begun on Welsh farms can end in the mission compound at Rorke’s Drift, and nowhere is that more vividly felt than here. Who in 1821 had heard of Missolonghi, Peta, or any of the other battle honours that punctuate the lists of Philhellene dead? What was it that brought William Washington here from America, to die on a British flagship in the harbour at Nauplia, killed by a Greek bullet? Or the nineteen-year-old Heise from Hanover to Peta – only to be beheaded on the field if he was lucky, and if not, forced to carry his comrades’ heads back to Arta before being impaled on the grey castellated walls of its Frankish citadel?

‘We are all Greeks,’3 Shelley proclaimed in 1821 with the largesse of a man firmly lodged in Italy, and yet if Washington and Heise might well have made the same claim it is less clear what they would have meant. There are certainly men here who would have echoed the language of Shelley’s ‘Hellas’, homeless refugees from monarchical despotism who would have died to keep the seventeen-year-old scion of the house of Wittelsbach or any other royal line out of Greece. There were men again for whom the war was a crusade, fought with all the polemical and emotional bitterness of religious war. ‘I wholly wish,’ one volunteer wrote, ‘to annihilate, extirpate and destroy those swarms and hordes of people called Turk.’4 Others fought because they had always fought and knew nothing else. There were young Byronists absorbed in some designer war of their own invention, charlatans attracted by the hope of profit, classicists infatuated with Greece’s past, Benthamite reformers, ageing Bonapartists – and then all those there for a dozen different motives, who might just once have known why they came but had long forgotten by the time they died.

‘For the most part the scum of their country,’ the English volunteer Frank Abney Hastings harshly wrote of them, ‘perhaps no crime can be named that might not have been found among the corps called Philhellenes.’5 This was a verdict, too, which Greek indifference would seem to have endorsed but one need only point to Hastings himself to qualify that judgement.* Or to Number 18 among the Missolonghi dead on the monument, General Normann – the same Normann who had found himself on different sides during the Napoleonic wars, fighting first against, then for, and finally against the French as his native Württemberg changed allegiance. He was in Greece as much to restore his tattered credit in his own eyes as in those of the world. Wounded at Peta, the man who had fought with the Austrians at Austerlitz and with the Grand Army on the retreat from Moscow, died grief-stricken at Missolonghi, finally broken by the last and bitterest disaster of his life.

There are twenty-five dead listed on this monument under Missolonghi; thirty-five under Nauplia; a single name, a man called Coffy, under Mitika; three under Parnassus and so on. In the first and last stages of the war some of these fought and died alongside their comrades, but for most of them these were lonely deaths in a struggle that had no shape and almost no battles, a conflict that wasted lives with a casual and purposeless savagery. There are no decorations after men’s names on this monument, no MM’s, no Croix de Guerre to suggest their courage or folly was ever recognized; no battalion names – no East Kents, no Artists’ Rifles, no Manchester Regiments – to promise any sense of comradeship. Some of them died of their wounds, some died mad, killed themselves or wasted from diseases. Some were killed by the Turks, others by the Greeks they had come to defend. Lord Charles Murray, a son of the Duke of Atholl, rich, generous and unbalanced, died in Gastoumi with a single dollar in his pocket. The eighteen year old Paul-Marie Bonaparte ran away from the university of Bologna only to shoot himself while cleaning his gun before he had so much as seen action. His corpse was kept for five years in a keg of rum in a Spetses monastery before being laid to rest on the island of Sphacteria.*

One of the more surprising ironies of history that this monument brings out is that if there was a single country that was relatively untouched by the excitement which swept Europe in 1821 it was Greece’s friend of popular mythology, Britain. It is true that in Thomas Gordon and Frank Abney Hastings Britain sent two of the wealthiest and most influential of the early Philhellenes, and yet in spite of all the committees formed and the pamphlets written, for a whole gamut of reasons that range from party politics to an oddly modern-looking compassion fatigue, no more than a dozen Britons actually made the journey out to Greece to fight during the first two years of the war.†

In the July of 1823, however, an ill-assorted menagerie of animals and men sailed from Genoa in an ugly, round-bottomed ‘tub’ on a voyage that would change this for good and hijack for Britain a place in Philhellene history it has never lost.

On board was the greatest of all Philhellenes, Lord Byron, and at his side a figure who embodies more vividly than anyone else the impact for good and ill that Byron had on the generation of Romantics who went to fight for Greek independence. With the exception of Byron he is probably the only English volunteer of whom anyone has heard, and yet for all that he said and wrote of himself in a lifetime of ruthless self-promotion there is scarcely a fact from his birth onwards that biography has not had to prise free of the lies with which he covered his tracks. He called himself one thing when the parish register gives another, claimed the friendship of Keats when he never met him; railed at his poverty with a private income, and boasted of an exotic past as a pirate when he was no more than a failed midshipman with the diluted romance of his family name, a squalid divorce and a musket ball in a knee to show for his first thirty years.

‘But tell me, who is this odd fish?’ Keats’s friend Joseph Severn demanded when he first met him in 1822 and it is a question biographers have been trying to answer ever since.6 To modern scholarship he is one of the great obstacles to historical truth, a compulsive braggart and liar. To the late Victorians he was the last apostolic link with its Romantic past, the intimate of Byron and Shelley through whom the ‘mighty dead’ spoke to a smaller and meaner age.7 To his contemporaries though – more vivid, more imaginatively ‘true’ than either the Grand Old Man of Millais’ portrait or the fraud of modern research – he was the man Severn himself dubbed ‘Lord Byron’s Jackal’;8 the man known to his friends with an impartiality which perhaps suggests why his name is not among the Philhellene dead, as ‘Greek’ or ‘Turk’ Trelawny.

1 THE WOLF CUB

My birth was unpropitious. I came into the world, branded and denounced as a vagrant; for I was a younger son of a family, so proud of their antiquity, that even gout and mortgaged estates were traced, many generations back, on the genealogical tree, as ancient heirlooms of aristocratic origin, and therefore reverenced. In such a house a younger son was like the cub of a felon wolf in good King Edgar’s days, when a price was set upon his head.

Trelawny’s Adventures of a Younger Son 1

ONE OF the most depressing assumptions of modern biography is the belief that the truth of men’s or women’s lives always lies in the trivia of their existence. There is often a devotion to the minutiae of a subject’s life that no biographer would dream of expending on his own, a kind of displaced egotism which produces the biographical equivalent of ‘Parnassian’ poetry or possession football, an intricate and over burdened account which bears as much relation to the proper business of biography as chronicle does to history.

The most part of most lives is no more interesting than that of a cat and as both subject and practitioner of biography no one better illustrates this fact than Edward John Trelawny. At some stage in an obscure and embittered youth he seems to have taken stock of his early years, found them wanting in every detail and invented for himself a wilder and more glamorous history of rebellion and adventure which he then successfully maintained in conversation and print for another sixty years.

Of all the silences open to a human being on the subject of himself, Trelawny’s is that of a man who knows how little of interest there is to say, and there is an important lesson to be learned from his deception. There are certainly writers like Shelley or Dickens whose creative life is intimately connected with the rhythms and textures of everyday existence, but the ‘Trelawny’ who still matters, the ‘Trelawny’ Byron and Shelley could both call friend, is the ‘Trelawny’ of myth and not dull reality, the romantic hero who sprang frilly formed from out of his own fantasies and not the failed midshipman modern scholarship has put in its place.

Edward John Trelawny was born on 13 November 1792, that rich and varied year in the history of English Romanticism, the year which saw the birth not just of two of its greatest leaders in Shelley and John Keble but of its hidden and unsuspected nemesis in the infant shape of the future ‘Princess of the Parallelograms’ and wife to Lord Byron, Anne Isabella Milbanke. Through both his parents Trelawny was descended from some of the most colourful figures in English and West Country history, and at the end of the eighteenth century the senior branches of his mother’s and father’s families were still wealthy and important landowners in their native Cornwall. In later years Trelawny usually claimed to have been born in Cornwall himself, but whatever he inherited in terms of character from West Country forebears who fought at Agincourt and against the Armada, the less romantic setting for his own birth was almost certainly his grandfather’s house in Soho Square from where, on 29 November, he was baptized John in the parish church of St Mary Le Bone.

The little we know of his early life comes from a work of fiction that the forty-year old Trelawny foisted on a credulous world as ‘autobiography’ under the title of Adventures of a Younger Son. There is no more than a tiny fraction of it that careful examination has left intact as reliable history, but if among all the fantasies with which he embroidered his life there is one subject on which he can be trusted it is that of his parents, as unlovely a couple from all existing evidence as even their son portrayed. His father was a Charles Trelawny, a younger son himself and an impoverished lieutenant-colonel in the Coldstream Guards; his mother was Mary Hawkins, a sister of Sir Christopher Hawkins Bt., of Trewithen, ‘a dark masculine woman of three and twenty’ with nothing to recommend her but an inheritance.2 They met at a ball. He was the handsomest man in the room, she apparently the richest catch. In the eyes of the impoverished twenty-nine-year-old officer, wrote their son with that dry economy which characterizes his best prose, ‘Rich and beautiful soon became synonymous’.

He received marked encouragement from the heiress. He saw those he had envied, envying him. Gold was his God, for he had daily experienced those mortifications to which the want of it subjected him; he determined to offer up his heart to the temple of Fortune alone, and waited but an opportunity of displaying his apostacy to love. The struggle with his better feelings was of short duration. He called his conduct prudence and filial obedience – and those are virtues – thus concealing its naked atrocity by a seemly covering.… But why dwell on an occurrence so common in the world, the casting away of virtue and beauty for riches, though the devil gives them? He married; found the lady’s fortune a great deal less, and the lady a great deal worse than he had anticipated: went to town irritated and disappointed, with the consciousness of having merited his fate; sunk part of his fortune in idle parade to satisfy his wife; and his affairs being embarrassed by the lady’s extravagance, he was, at length, compelled to sell out of the army, and retire to economise in the country.3

In the history and literature of a century famous for its battles of the generations, it is doubtful whether even Shelley or Samuel Butler pursued their fathers’ memory with the same dogged and public hatred that Trelawny showed for his. There is a notorious tale he tells in Adventures of what he calls his first childhood ‘duel’,4 a mythic battle to the death with his father’s pet raven which in its capacity for violence and surrogate vengeance is the archetype of all the real and imagined struggles of his life ahead, of those fights with maddened stallions or the savage encounters with figures in authority who seemed to his adult mind the reincarnations of early tyranny.

One day I had a little girl for my companion, whom I had enticed from the nursery to go with me to get some fruit clandestinely. We slunk out, and entered the garden unobserved. Just as we were congratulating ourselves under a cherry-tree, up comes the accursed monster of a raven. It was no longer to be endured. He seized hold of the little girl’s frock; she was too frightened to scream; I did not hesitate an instant. I told her not to be afraid, and threw myself upon him. He let her go, and attacked me with bill and talon. I got hold of him by the neck, and heavily lifting him up, struck his body against the tree and the ground …

His look was now most terrifying: one eye was hanging out of his head, the blood coming from his mouth, his wings flapping the earth in disorder, and with a ragged tail, which I had half plucked by pulling at him during his first execution. He made a horrid struggle for existence, and I was bleeding all over. Now, with the aid of my brother, and as the raven was exhausted by exertion and wounds, we succeeded in gibbeting him again; and then with sticks we cudgelled him to death, beating his head to pieces. Afterwards we tied a stone to him, and sunk him in the duck-pond.5

Trelawny was five at the time of this incident, but there is no record of where it might have taken place. Judging from Adventures and the baptismal records of the successive children born to his increasingly gloomy parents, the Trelawny family lived a peripatetic life during his early years, moving between rented houses in the country, his maternal uncle John Hawkins’s seat at Bignor in Sussex and the family house of his grandfather, General Trelawny, at 9 Soho Square. When Trelawny was six his father had taken on the name of Brereton and with it a large fortune. Yet even with this new wealth there seems to have been no thought of an education for Trelawny and he grew up by his own account an intractable and surly boy, unloved and unloving, as large, bony and awkward as his mother and as violent in his moods as his father.

It was one of his father’s outbursts of temper that led, when he was about nine or ten, to his being literally frog-marched with his older brother Henry, to a private establishment in Bristol for his first experience of school. It was a bleakly forbidding building, enclosed within high walls and, to a child’s eyes, more like a prison. ‘He is savage, incorrigible! Sir, he will come to the gallows, if you do not scourge the devil out of him,’6 was his father’s parting injunction to the headmaster. The Reverend Samuel Seyer, incongruously small, dapper and powdered for a man who was a savage disciplinarian even by the standards of the day, eagerly embraced the advice. As a pupil of his, Trelawny later recalled with a nice discrimination, he was caned most hours and flogged most days. It was when he finally turned on his attackers, half-strangling the under master and assaulting Seyer himself, that he was sent home, as ignorant as the day he arrived two years earlier. ‘Come, Sir, what have you learnt,’ his father demanded of him.

‘Learnt!’ I ejaculated, speaking in a hesitant voice, for my mind misgave me as to what was to follow.

‘Is that the way to address me? Speak out, you dunce! and say, Sir! Do you take me for a foot-boy?’ raising his voice to a roar, which utterly drove out of my head what little the school-master had, with incredible toil and punishment, driven into it. ‘What have you learnt, you ragamuffin? What do you know?’

‘Not much, Sir!’

‘What do you know in Latin?’

‘Latin, Sir? I don’t know Latin, Sir!’

‘Not Latin, you idiot! Why, I thought they taught nothing but Latin.’

‘Yes, Sir; – cyphering.’

‘Well, how far did you proceed in arithmetic?’

‘No, Sir! – they taught me cyphering and writing.’

My father looked grave. ‘Can you work the rule of three, you dunce?’

‘Rule of three, Sir?’

‘Do you know subtraction? Come, you blockhead, answer me! Can you tell me, if five are taken from fifteen, how many remain?’

‘Five and fifteen, Sir, are – ’counting on my fingers, but missing my thumb, ‘are – are – nineteen, Sir!’

‘What! you incorrigible fool! – Can you repeat your multiplication table?’

‘What table, Sir?’

Then turning to my mother, he said: ‘Your son is a downright idiot, Madam, – perhaps knows not his own name. Write your name, you dolt!’

‘Write, Sir? I can’t write with that pen, Sir; it is not my pen.’

‘Then spell your name, you ignorant savage!’

‘Spell, Sir?’ I was so confounded that I misplaced the vowels. He arose in wrath, overturned the table, and bruised his shins in attempting to kick me, as I dodged him, and rushed out of the room.7

As the poet James Michie once remarked, the fact that a man lies most of the time does not mean he lies all of the time, but with Trelawny it is as well to be sceptical. There is no way of knowing whether this exchange, any more than the duel with the raven, actually occurred, and yet what is perhaps more important is that even as a history of Trelawny’s inner life Adventures needs to be treated with a caution that has not always been shown.

There is an obvious sense in which this same wariness has to be extended to all autobiographies, consciously or unconsciously shaping and selecting material as they inevitably do, but with Trelawny the timing of his Adventures makes it of particular relevance. There seems no doubt that the miseries he describes in its pages were real enough, and yet by the time that he came to put them in written form in 1831, the friendships of Byron and Shelley had armed him with a self-dramatizing language of alienation and revolt that enabled him to invest his infant battles with a stature and significance which seem curiously remote from the prosaic reality of childhood unhappiness.

For all that, though, it is clear that the young Trelawny felt and resented these indignities with an unusual intensity. There was an innate physical and mental toughness about him which equipped him for survival in even the most alien of worlds, and yet beneath a hardening carapace of indifference that sense of injustice and emotional betrayal which would fuel his whole life was festering dangerously. On his first night at school, as he lay on a beggarly pallet of a bed, the rush-lights extinguished, he had listened to the snores of his fellow pupils and stifled the sobs that would have betrayed his misery. The child who two years later escaped Seyer’s joyless and savage regime would allow no such weakness in his makeup, no vulnerability. Deprived of affection, he had learned the power of brute strength and domination, the virtue of self-reliance. He had become, he says in his richest Romantic strain, ‘callous’, ‘sullen’, ‘Vindictive’, ‘insensible’ and ‘indifferent to shame and fear’.8 ‘The spirit in me was gathering strength,’ he proudly recalled, ‘in despite of every endeavour to destroy it, like a young pine flourishing in the cleft of a bed of granite.’9