Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

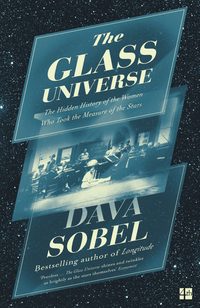

Czytaj książkę: «The Glass Universe: The Hidden History of the Women Who Took the Measure of the Stars»

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

First published in the USA by Viking Books in 2016

Copyright © 2016 John Harrison and Daughter, Ltd.

The right of Dava Sobel to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover images © Harvard University Archives, UAV 630.271 (D3091) (olvwork432332) / Harvard College Observatory (Harvard Women Computers, c. 1925)

Frontispiece image courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Insert page 1, bottom: Angelo Secchi, Le soleil, 1875–1877; page 2, top: Courtesy of Carbon County Museum, Rawlins, Wyoming; page 3, bottom: UAV 630.271 (E4116), Harvard University Archives; page 4, top: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory; page 5, top: Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University; page 5, bottom: Courtesy of Hastings Historical Society, New York; page 6, top: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory; page 6, bottom: Lindsay Smith, used with permission; page 7, top: HUGFP 125.82p, Box 2, Harvard University Archives; page 7, bottom: Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library; page 8, top: HUPSF Observatory (14), olvwork360662, Harvard University Archives; pages 8–9, bottom: UAV 630.271 (391), olvwork432043, Harvard University Archives; page 9, top: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory; page 10, top: HUGFP 125.82p, Box 2, Harvard University Archives; page 10, bottom: Courtesy of Harvard College Observatory; page 11, top: HUGFP 125.36 F, Box 1, Harvard University Archives; page 11, bottom: HUGFP 125.36 F, Box 1, Harvard University Archives; page 12, bottom left and right: Courtesy of Katherine Haramundanis; page 13, top: Courtesy of the Harvard University Archives; page 13, bottom: Courtesy of Charles Reynes; page 14: Chart 1, Volume 105, Harvard College Observatory Annals; page 15, top: Courtesy of Hastings Historical Society, New York; page 15, bottom: Courtesy of Katherine Haramundanis; page 16, top: Lia Halloran, used with permission; page 16, bottom: Richard E. Schmidt, used with permission

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007548200

Ebook Edition © November 2017 ISBN: 9780007548194

Version: 2017-09-14

To the ladies who sustain me:

Diane Ackerman, Jane Allen,

KC Cole, Mary Giaquinto, Sara James, Joanne Julian,

Zoë Klein, Celia Michaels, Lois Morris,

Chiara Peacock, Sarah Pillow,

Rita Reiswig, Lydia Salant, Amanda Sobel,

Margaret Thompson, and Wendy Zomparelli,

with love and thanks

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

PART ONE

The Colors of Starlight

CHAPTER ONE

Mrs. Draper’s Intent

CHAPTER TWO

What Miss Maury Saw

CHAPTER THREE

Miss Bruce’s Largesse

CHAPTER FOUR

Stella Nova

CHAPTER FIVE

Bailey’s Pictures from Peru

PART TWO

Oh, Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me!

CHAPTER SIX

Mrs. Fleming’s Title

CHAPTER SEVEN

Pickering’s “Harem”

CHAPTER EIGHT

Lingua Franca

CHAPTER NINE

Miss Leavitt’s Relationship

CHAPTER TEN

The Pickering Fellows

PART THREE

In the Depths Above

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Shapley’s “Kilo-Girl” Hours

CHAPTER TWELVE

Miss Payne’s Thesis

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

The Observatory Pinafore

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Miss Cannon’s Prize

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

The Lifetimes of Stars

Picture Section

Appreciation

Sources

Some Highlights in the History of the Harvard College Observatory

Glossary

A Catalogue of Harvard Astronomers, Assistants, and Associates

Remarks

Bibliography

Also by Dava Sobel

About the Author

About the Publisher

PREFACE

A LITTLE PIECE OF HEAVEN. That was one way to look at the sheet of glass propped up in front of her. It measured about the same dimensions as a picture frame, eight inches by ten, and no thicker than a windowpane. It was coated on one side with a fine layer of photographic emulsion, which now held several thousand stars fixed in place, like tiny insects trapped in amber. One of the men had stood outside all night, guiding the telescope to capture this image, along with another dozen in the pile of glass plates that awaited her when she reached the observatory at 9 a.m. Warm and dry indoors in her long woolen dress, she threaded her way among the stars. She ascertained their positions on the dome of the sky, gauged their relative brightness, studied their light for changes over time, extracted clues to their chemical content, and occasionally made a discovery that got touted in the press. Seated all around her, another twenty women did the same.

The unique employment opportunity that the Harvard Observatory afforded ladies, beginning in the late nineteenth century, was unusual for a scientific institution, and perhaps even more so in the male bastion of Harvard University. However, the director’s farsighted hiring practices, coupled with his commitment to systematically photographing the night sky over a period of decades, created a field for women’s work in a glass universe. The funding for these projects came primarily from two heiresses with abiding interests in astronomy, Anna Palmer Draper and Catherine Wolfe Bruce.

The large female staff, sometimes derisively referred to as a harem, consisted of women young and old. They were good at math, or devoted stargazers, or both. Some were alumnae of the newly founded women’s colleges, though others brought only a high school education and their own native ability. Even before they won the right to vote, several of them made contributions of such significance that their names gained honored places in the history of astronomy: Williamina Fleming, Antonia Maury, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Annie Jump Cannon, and Cecilia Payne. This book is their story.

PART ONE

The Colors of Starlight

I swept around for comets about an hour, and then I amused myself with noticing the varieties of color. I wonder that I have so long been insensible to this charm in the skies, the tints of the different stars are so delicate in their variety. … What a pity that some of our manufacturers shouldn’t be able to steal the secret of dyestuffs from the stars.

—Maria Mitchell (1818–1889)

Professor of Astronomy, Vassar College

The white mares of the moon rush along the sky

Beating their golden hoofs upon the glass heavens

—Amy Lowell (1874–1925)

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry

CHAPTER ONE

Mrs. Draper’s Intent

THE DRAPER MANSION, uptown on Madison Avenue at Fortieth Street, exuded the new glow of electric light on the festive night of November 15, 1882. The National Academy of Sciences was meeting that week in New York City, and Dr. and Mrs. Henry Draper had invited some forty of its members to dinner. While the usual gaslight illuminated the home’s exterior, novel Edison incandescent lamps burned within—some afloat in bowls of water—for the amusement of the guests at table.

Thomas Edison himself sat among them. He had met the Drapers years ago, on a camping trip in the Wyoming Territory to witness the total solar eclipse of July 29, 1878. During that memorable interlude of midday darkness, as Mr. Edison and Dr. Draper executed their planned observations, Mrs. Draper had dutifully called out the seconds of totality (165 in all) for the benefit of the entire expedition party, from inside a tent, where she remained secluded, blind to the spectacle, lest the sight of it unnerve her and cause her to lose count.

The red-haired Mrs. Draper, an heiress and a renowned hostess, surveyed her electrified salon with satisfaction. Not even Chester Arthur in the White House lighted his dinner parties with electricity. Nor could the president attract a more impressive assembly of science’s luminaries. Here she welcomed the well-known zoologists Alexander Agassiz, down from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Spencer Baird, up from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. She introduced her family friend Whitelaw Reid of the New York Tribune to Asaph Hall, world famous for his discovery of Mars’s two moons, and to solar expert Samuel Langley, as well as to the directors of every prominent observatory on the Eastern Seaboard. No astronomer in the country could refuse an invitation to the home of Henry Draper.

It was her home, in fact—her childhood home, built by her late father, the railroad and real estate magnate Cortlandt Palmer, long before the neighborhood became fashionable. Now she made certain the house suited Henry as perfectly as she did, with its entire third floor converted into his machine workshop, and the loft over the stable repurposed as his chemical laboratory, which he reached via a covered walkway connected to the dwelling.

She had barely heeded the stars before meeting Henry, any more than she regarded grains of sand at the shore. He was the one who pointed out to her their subtle colors and differences in brightness, even as he whispered his dream of abjuring medicine for astronomy. If she feigned interest at first to please him, she had long since found her own passion, and proved a willing partner in observation as in marriage. How many nights had she knelt by his side in the cold and dark, spreading foul-smelling emulsion on the glass photographic plates he used with his handcrafted telescopes?

A glance at Henry’s plate confirmed he had not touched the banquet fare. He was fighting a cold, or perhaps it was pneumonia. A few weeks earlier, while he and his old Union Army pals were hunting in the Rocky Mountains, a blizzard had struck and stranded them above the timberline, far from shelter. The chill and exhaustion of that exposure still plagued Henry. He looked terrible, as though suddenly an old man at forty-five. Yet he continued chatting amiably with the company, explaining anew, each time anyone asked, how he had generated steady current for the Edison lamps from his own gas-powered dynamo.

Soon she and Henry would be leaving the city for their private observatory upriver at Hastings-on-Hudson. Now that he had finally resigned his professorship on the faculty at New York University, they could devote themselves to his most important mission. In their fifteen shared years, she had seen his landmark achievements in stellar photography win him all manner of acclaim—his 1874 gold medal from Congress, his election to the National Academy of Sciences, his status as a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. What would the world say when her Henry resolved the seemingly intractable age-old mystery of the chemical composition of the stars?

After bidding the guests good-night at the close of that glittering evening, Henry Draper took a hot bath, then took to his bed, and stayed there. Five days later he was dead.

• • •

IN THE OUTFLOW OF CONDOLENCES following her husband’s funeral, Anna Palmer Draper drew some comfort from a correspondence with Professor Edward Pickering of the Harvard College Observatory, one of the guests at the Academy gathering the night of Henry’s collapse.

“My dear Mrs. Draper,” Pickering wrote on January 13, 1883, “Mr. Clark [of Alvan Clark & Sons, the preeminent telescope makers] tells me that you are preparing to complete the work in which Dr. Draper was engaged, and my interest in this matter must be my excuse for addressing you regarding it. I need not state my satisfaction that you are taking this step, since it must be obvious that in no other way could you erect so lasting a monument to his memory.”

This was indeed Mrs. Draper’s intention. She and Henry had no children to carry on his legacy, and she had resolved to do so on her own.

“I fully appreciate the difficulty of your task,” Pickering continued. “There is no astronomer in this country whose work would be so hard to complete as Dr. Draper’s. He had that extraordinary perseverance and skill which enabled him to secure results after trials and failures which would have discouraged anyone else.”

Pickering referred specifically to the doctor’s most recent photographs of the brightest stars. These hundred-some pictures had been taken through a prism that split starlight into its spectrum of component colors. Although the photographic process reduced the rainbow hues to black and white, the images preserved telltale patterns of lines within each spectrum—lines that hinted at the stars’ constituent elements. In after-dinner conversation at the November gala, Pickering had offered to help decipher the spectral patterns by measuring them with specialized equipment at Harvard. The doctor had declined, confident that his new freedom from teaching at NYU would allow him time to build his own measuring apparatus. But now all that had changed, and so Pickering repeated the offer to Mrs. Draper. “I should be greatly pleased if I might do something in memory of a friend whose talents I always admired,” he wrote.

“Whatever may be your final arrangements regarding the great work you have undertaken,” Pickering said in closing, “pray recollect that if I can in any way advise or aid you, I shall be doing but little to repay Dr. Draper for a friendship which I shall always value, but which can never be replaced.”

Mrs. Draper rushed to reply just a few days later, January 17, 1883, on notepaper edged in black.

“My dear Prof. Pickering:

“Thanks so very much for your kind and encouraging letter. The only interest I can now take in life will be in having Henry’s work continued, yet I feel so very incompetent for the task that my courage sometimes completely fails me— I understand Henry’s plans and his manner of working, perhaps better than anyone else, but I could not get along without an assistant and my main difficulty is to find a person sufficiently acquainted with physics, chemistry, and astronomy to carry on the various researches. I will probably find it necessary to have two assistants, one for the Observatory and one for the laboratory work, for it is not likely that I will find any one person with the varied scientific knowledge that was peculiar to Henry.”

She was prepared to pay good salaries in order to draw the most qualified men as assistants. She and her two brothers had inherited their father’s vast real estate holdings, and Henry had managed her share of the fortune to excellent effect.

“It is so hard that he should be taken away just as he had arranged all his affairs to have time to do the work he really enjoyed, and in which he could have accomplished so much. I cannot be reconciled to it in any way.” Nevertheless she hoped to get the work running as soon as possible under her own direction, and “then, when I can buy the place at Hastings where the Observatory is, to do so.”

Henry had built the facility on the grounds of a country retreat owned by his father, Dr. John William Draper. The elder Dr. Draper, the first physician in the family to mix medicine with active research in chemistry and astronomy, had died a widower the previous January. His will bequeathed his entire estate to his beloved spinster sister, Dorothy Catherine Draper, who had founded and run a girls’ school in her youth to finance his education. It was not yet clear whether Henry’s widow would win control of the Hastings property as she wished, and move Henry’s Madison Avenue laboratory there, and endow the site as an institution for original research, to be named the Henry Draper Astronomical and Physical Observatory.

“As long as I could I should keep the direction of the institution myself,” she told Pickering. “It seems the only suitable memorial I can erect to Henry, and the only way to perpetuate his name and his work.”

At the end she entreated Pickering’s counsel. “I am so unusually alone in the world, that without feeling that those friends who were interested in Henry’s work would advise me, I could not do anything.”

Pickering encouraged her to publish her husband’s findings to date, since it might take her a long time to add to them. Once again he extended his offer to examine the glass photographic plates on the measuring machine at Harvard, if she would be so good as to send him some.

Mrs. Draper agreed but thought it best to deliver the plates in person. They were small objects, only about an inch square each.

“I may be obliged to go to Boston in the course of the next ten days to attend to some business matters with one of my brothers,” she wrote on January 25. “If so I could take the negatives with me and by going to Cambridge for part of a day, if it was convenient for you, could look over the pictures with you, and see what you think of them.”

As arranged, she reached Summerhouse Hill above Harvard Yard on Friday morning, February 9, accompanied by her husband’s close friend and colleague George F. Barker of the University of Pennsylvania. Barker, who was preparing a biographical memoir of Henry, had been the Drapers’ houseguest at the time of the Academy dinner. Late that night, when Henry was seized with a violent chill while bathing, it was Barker who helped lift him from the tub and carry him to the bedroom. Then he bid the Drapers’ neighbor and physician Dr. Metcalfe, another dinner guest, to return to the house immediately. Dr. Metcalfe diagnosed double pleurisy. Although Henry of course received the most tender nursing—and showed some brief promise of improvement—the infection spread to his heart. On Sunday the doctor noted the signs of pericarditis, which precipitated Henry’s death at about four o’clock Monday morning, the twentieth of November.

• • •

MRS. DRAPER HAD VISITED OBSERVATORIES with her husband in Europe and the States, but she had not set foot inside one in months. At Harvard, the large domed building that housed the several telescopes doubled as the director’s residence. Both Professor and Mrs. Pickering ushered her into the pleasant rooms and made her feel welcome.

Mrs. Pickering, née Lizzie Wadsworth Sparks, daughter of former Harvard president Jared Sparks, did not aid her husband in his observations, as Mrs. Draper had done, but acted as the institution’s vivacious and charming hostess.

An exaggerated though genuine politeness characterized the directorial style of Edward Charles Pickering. If the observatory’s financial straits constrained him to pay his eager young assistants meager wages, nothing prevented his addressing them respectfully as Mr. Wendell or Mr. Cutler. He called the senior astronomers Professor Rogers and Professor Searle, and all but doffed his hat and bowed to the ladies—Miss Saunders, Mrs. Fleming, Miss Farrar, and the rest—who arrived each morning to perform the necessary calculations upon the nighttime observations.

Was it usual, Mrs. Draper wondered, to employ women as computers? No, Pickering told her, as far as he knew the practice was unique to Harvard, which currently retained six female computers. While it would be unseemly, Pickering conceded, to subject a lady to the fatigue, not to mention the cold in winter, of telescope observing, women with a knack for figures could be accommodated in the computing room, where they did credit to the profession. Selina Bond, for example, was the daughter of the observatory’s revered first director, William Cranch Bond, and also the sister of his equally revered successor, George Phillips Bond. She was currently assisting Professor William Rogers in fixing the exact positions (in the celestial equivalents of latitude and longitude) for the several thousand stars in Harvard’s zone of the heavens, as part of a worldwide stellar mapping project administered by the Astronomische Gesellschaft in Germany. Professor Rogers spent every clear night at the large transit instrument, noting the times individual stars crossed the spider threads in the eyepiece. Since air—even clear air—bent the paths of light waves, shifting the stars’ apparent positions, Miss Bond applied the mathematical formula that corrected Professor Rogers’s notations for atmospheric effects. She used additional formulas and tables to account for other influential factors, such as Earth’s progress in its annual orbit, the direction of its travel, and the wobble of its axis.

Anna Winlock, like Miss Bond, had grown up at the observatory. She was the eldest child of its inventive third director, Joseph Winlock, Pickering’s immediate predecessor. Winlock had died of a sudden illness in June 1875, the week of Anna’s graduation from Cambridge High School. She went to work soon afterward as a computer to help support her mother and younger siblings.

Williamina Fleming, in contrast, could claim no familial or collegiate connection to the observatory. She had been hired in 1879, on the residence side, as a second maid. Although she had taught school in her native Scotland, certain circumstances—her marriage to James Orr Fleming, her immigration to America, her husband’s abrupt disappearance from her life—forced her to seek employment in a “delicate condition.” When Mrs. Pickering recognized the new servant’s abilities, Mr. Pickering reassigned her as a part-time copyist and computer in the other wing of the building. No sooner had Mrs. Fleming mastered her tasks in the observatory than the impending birth of her baby sent her home to Dundee. She stayed there more than a year after her confinement, then returned to Harvard in 1881, having left her son, Edward Charles Pickering Fleming, in the care of her mother and grandmother.

• • •

NONE OF THE PROJECTS UNDER WAY at the observatory looked familiar to Mrs. Draper. Henry’s amateur standing and private means had freed him to follow his own interests at the forefront of stellar photography and spectroscopy, while the professional staff here in Cambridge hewed to more traditional pursuits. They charted the heavens, monitored the orbits of planets and moons, tracked and communicated the courses of comets, and also provided time signals via telegraph to the city of Boston, six railroads, and numerous private enterprises such as the Waltham Watch Company. The work demanded both scrupulous attention to detail and a large capacity for tedium.

When the thirty-year-old Pickering took over as director on February 1, 1877, his primary responsibility had been to raise enough money to keep the observatory solvent. It received no support from the college to pay salaries, purchase supplies, or publish the results of its labors. Aside from interest on its endowment and income from its exact-time service, the observatory depended entirely on private bequests and contributions. A decade had passed since the last solicitation for funds. Pickering soon convinced some seventy astronomy enthusiasts to pledge $50 to $200 per year for five years, and while those subscriptions trickled in, he sold the grass cuttings from the six-acre observatory grounds at a small profit. (They brought in about $30 a year, or enough to cover some 120 hours’ worth of computing time.)

Born and bred on Beacon Hill, Pickering navigated easily between the moneyed Boston aristocracy and the academic halls of Harvard University. In his ten years spent teaching physics at the fledgling Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he had revolutionized instruction by setting up a laboratory where students learned to think for themselves while solving problems through experiments that he designed. Pursuing his own research at the same time, he explored the nature of light. He also built and demonstrated, in 1870, a device that transmitted sound by electricity—a device identical in principle to the one perfected and patented six years later by Alexander Graham Bell. Pickering, however, never thought to patent any of his inventions because he believed scientists should share ideas freely.

At Harvard, Pickering chose a research focus of fundamental importance that had been neglected at most other observatories: photometry, or the measurement of the brightness of individual stars.

Obvious contrasts in brightness challenged astronomers to explain why some stars outshone others. Just as they ranged in color, stars apparently came in a range of sizes, and existed at different distances from Earth. Ancient astronomers had sorted them along a continuum, from the brightest of “first magnitude” down to “sixth magnitude” at the limit of naked-eye perception. In 1610 Galileo’s telescope revealed a host of stars never seen before, pushing the lower limit of the brightness scale to tenth magnitude. By the 1880s, large telescopes the likes of Harvard’s Great Refractor could detect stars as faint as fourteenth magnitude. In the absence of uniform scales or standards, however, all estimations of magnitude remained the judgment calls of individual astronomers. Brightness, like beauty, was defined in the eye of the beholder.

Pickering sought to set photometry on a sound new basis of precision that could be adopted by anyone. He began by choosing one brightness scale among the several currently in use—that of English astronomer Norman Pogson, who calibrated the ancients’ star grades by presuming first-magnitude stars to be precisely a hundredfold brighter than those of sixth. That way, each step in magnitude differed from the next by a factor of 2.512.

Pickering then chose a lone star—Polaris, the so-called polestar or North Star—as the basis for all comparisons. Some of his predecessors in the 1860s had gauged starlight in relation to the flame of a kerosene lamp viewed through a pinhole, which struck Pickering as tantamount to comparing apples with oranges. Polaris, though not the sky’s brightest star, was thought to give an unwavering light. It also remained fixed in space above Earth’s north pole, at the hub of heavenly rotation, where its appearance was least susceptible to distortion by currents of intervening air.

With Pogson’s scale and Polaris as his guides, Pickering devised a series of experimental instruments, or photometers, for measuring brightness. The firm of Alvan Clark & Sons built some dozen of Pickering’s designs. The early ones attached to the Great Refractor—the observatory’s premier telescope, a gift from the local citizenry in 1847. Ultimately Pickering and the Clarks constructed a superior freestanding model they called the meridian photometer. A dual telescope, it combined two objective lenses mounted side by side in the same long tube. The tube remained stationary, so that no time was lost in repointing it during an observing session. A pair of rotating reflective prisms brought Polaris into view through one lens and a target star through the other. The observer at the eyepiece, usually Pickering, turned a numbered dial controlling other prisms inside the instrument, and thus adjusted the two lights until Polaris and the target appeared equally bright. A second observer, most often Arthur Searle or Oliver Wendell, read the dial setting and recorded it in a notebook. The pair repeated the procedure four times per star, for several hundred stars per night, exchanging places every hour to avoid making errors due to eye fatigue. In the morning they turned over the notebook to Miss Nettie Farrar, one of the computers, for tabulation. Taking Polaris’s arbitrarily assigned magnitude of 2.1 as her base, Miss Farrar arrived at relative values for the other stars, averaged and corrected to two decimal places. By these means, it took three years for Pickering and his crew to pin a magnitude on every star visible from the latitude of Cambridge.

The objects of Pickering’s photometry studies included some two hundred stars known to vary their light output over time. These variable stars, or “variables,” required the closest surveillance. In his 1882 report to Harvard president Charles Eliot, Pickering noted that thousands of observations were needed to establish the light cycle of any given variable. In one instance, “900 measures were made in a single night, extending without intermission from 7 o’clock in the evening until the variable had attained its full brightness, at half past 2 in the morning.”

Pickering needed reinforcements to keep watch over the variables. Alas, in 1882, he could not afford to hire even one additional staff member. Rather than dun the observatory’s loyal subscribers for more money, he issued a plea for volunteers from the ranks of amateur observers. He believed women could conduct the work as well as men: “Many ladies are interested in astronomy and own telescopes, but with two or three noteworthy exceptions their contributions to the science have been almost nothing. Many of them have the time and inclination for such work, and especially among the graduates of women’s colleges are many who have had abundant training to make excellent observers. As the work may be done at home, even from an open window, provided the room has the temperature of the outer air, there seems to be no reason why they should not thus make an advantageous use of their skill.”