Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer»

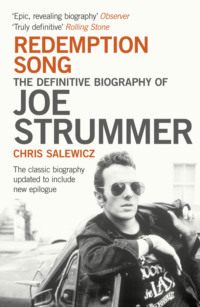

Redemption Song

The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

Chris Salewicz

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

1 STRAIGHT TO HEAVEN

2 R.I.PUNK

3 INDIAN SUMMER

4 STEPPING OUT OF BABYLON (ONE MORE TIME)

5 BE TRUE TO YOUR SCHOOL (LIKE YOU WOULD TO YOUR GIRL)

6 BLUE APPLES

7 THE MAGIC VEST

8 THE BAD SHOPLIFTER GOES GRAVEDIGGING

9 PILLARS OF WISDOM

10 ‘THIS MAN IS A STAR!’

11 I’M GOING TO BE A PUNK ROCKER

12 UNDER HEAVY MANNERS

13 THE ALL-NIGHT DRUG-PROWLING WOLF

14 RED HAND OF FATE

15 NEWS OF CLOCK NINE

16 1 MAY TAKE A HOLIDAY

17 THE NEWS BEHIND THE NEWS

18 ANGER WAS COOLER

19 SPANISH BOMBS

20 MAN OF MYSTERY

21 SOLDIERS OF MISFORTUNE

22 ON THE OTHER HAND …

23 THE RECKLESS ALTERNATIVE

24 THE COOL IMPOSSIBLE

25 THE EXCITEMENT GANG

26 LET’S ROCK AGAIN!

27 CAMPFIRE TALES

28 BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME

29 CODA (THE WEST)

EULOGY

PICTURE SECTION

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PRAISE FOR CHRIS SALEWICZ’S REDEMPTION SONG

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ROOTS OF HEATHEN

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

1

STRAIGHT TO HEAVEN

2002

This is how I heard about Joe’s death: Don Letts, the Rastafarian film director who had made all the Clash videos, called me at around 9.30 on the evening of 22 December 2002.

‘I’ve got to tell you, Chris: Joe’s died – of a heart attack.’

‘Oh-fuckin’-hell-Oh-fuckin’-hell-Oh-fuckin’-hell,’ was all I could say.

I poured a large glass of rum and stuck Don’s documentary about the group, Westway to the World, on the video. I called up Mick Jones, who in between sobs was his usual funny self, telling me how glad he was he’d played with Joe at the benefit for the Fire Brigades Union five weeks before.

‘I don’t even know what religion he was,’ Mick said.

‘Some kind of Scottish low-church Presbyterian, I imagine,’ I suggested.

‘Church of Beer, probably,’ laughed Mick, tearfully.

I went to bed late, and although I hardly slept I didn’t get up until around 9.30. At around 9.55 the phone rang: ITN News. Could they interview me for the 10.00 bulletin? I sat down on the sofa and made some quick soundbite-sized notes. I’m not even sure what I said. The phone rang again: the Independent wanted me to write an obituary, a long one, 2,000 words, by 4 o’clock. I started up the computer, opening up my assorted Strummer files, pulling out quotes and phrases. Then the phone rang once more: ITN News again. Could they send a car for me to be on the 12.30 News? Call me back in a minute, I said: I need to work out whether I can do it – the obituary is what counts most. I put the phone down. Someone’s got to do this for Joe, I thought, but I don’t want to blow the obit by doing too much. I called Joe’s home in Somerset and left a message of condolence for Lucinda, his widow.

By the time the car came for me at half eleven, I’d got a good amount done. As it always does, the TV stuff took much longer than it was meant to – they wanted to record something more for the evening news. It was 2.00 p.m. before I was home again. I still had a lot to do. But somehow time stretched, giving me many more minutes an hour than I might have expected. I e-mailed the obituary through at ten minutes to four. This is what I wrote:

The job of being Joe Strummer, spokesman for the punk generation and front-man for the Clash, never sat easily with the former John Mellor. Always prepared to give of himself to his fans, he still felt a weight of responsibility on his shoulders that often made him crave anonymity, as much as the natural performer within him needed the spotlight.

But when – after a hiatus of almost a decade and a half – he returned to recording and performing with his new group the Mescaleros in 1999, it was business as usual: seemingly the same huge amounts of energy, passion and heart-on-sleeve belief that were his trademark with the Clash and that drew a worldwide audience for him and the group. After a show the dressing-room or backstage bar still would be crammed with fans and friends as Joe held forth on the issues of the day, in his preferred role of pub philosopher and articulate rabble-rouser for the dispossessed. (But even here was the endless paradox of Joe Strummer: he could argue the case for Yorkshire pitworkers or homeless Latinos in Los Angeles, but if obliged to reveal himself through any interior observation, he would generally freeze. Even other members of the Clash would complain about his hopelessness at soul-baring.)

Yet when he played a show at London’s 100 Club two years ago, he was so exhausted afterwards that he had to lie down on the floor of the dressing-room: his Mescaleros’ set included a good percentage of Clash songs, and you worried that the frenetic speed at which they were performed would test the health of a man approaching his fiftieth birthday. In an irony that Joe Strummer no doubt would have appreciated, his death last Sunday afternoon came not from the stock rock’n’roll killers of drugs, drink or travel accidents, but after taking his dog for a walk at his home in Somerset: sitting down on a chair in his kitchen, he suffered a fatal heart attack. [I later learnt it was in his living-room, and it was ‘dogs’, not ‘dog’.]

Neither of his parents had lived to a ripe old age. Joe Strummer, who earned his sobriquet from his crunchy rhythm guitar style, was born in Ankara, Turkey, in 1952 to a career diplomat. Christened John Graham Mellor, he was sent at the age of ten [nine] to a minor public school, the City of London Freemen’s School at Ashtead Park in Surrey. He had already lived in Cairo, Mexico City (‘I remember the 1956 earthquake vividly; running to hide behind a brick wall, which was the worst thing to do,’ he once told me) and Bonn. Strummer’s father’s profession of career diplomat didn’t arise from any position of privilege – quite the opposite, in fact. ‘He was a self-made man, and we could never get on,’ said Strummer. ‘He couldn’t understand why I was last in every class at school. He didn’t understand there were different shapes to every piece of wood, different grains to people. I don’t blame him, because all he knew was that he pulled himself out of it by studying really hard.’

All the same, such a background was not especially appropriate in the mid-1970s punk world of supposed working-class heroes, which may explain why Strummer always seemed even more anarchic than his contemporaries. Mick Jones, like Strummer a former art-school student, discovered Joe when he was singing with squat-rock R’n’B group The 101’ers, and poached him for a group he was forming called the Clash, becoming his songwriting partner: matched to Jones’s zeitgeist musical arrangements, Strummer’s lyrics were the words of a satirical poet, and often hilariously funny – one of his first creative contributions on linking up with Mick Jones was to change the title of a love-song called ‘I’m So Bored with You’ to ‘I’m So Bored with the USA’. Verbal non-sequiturs were a speciality: his gasped aside of ‘vacuum-cleaner sucks up budgie’ at the end of ‘Magnificent Seven’, inspired by a newspaper headline on the studio floor, is one of the funniest lines in rock’n’roll.

Strummer had one brother, David, who was eighteen months older than himself. By the time he reached sixteen, the younger boy had become accustomed to his brother’s far-right leanings – he had joined the National Front – and to the fact that he was obsessed, ‘in a cheap paperback way’, with the occult. Was it this unpleasant cocktail that led David to commit suicide? Whatever, it was clearly a cathartic moment for his younger brother: Joe Strummer often seemed overhung by a mood of mild depression, a constant struggle.

After dropping out of Central College of Art (‘after about a week,’ [he lied about this]), he threw himself into the alternative world of squatting. Moving for a time to Wales, he spent one Christmas on acid listening to Big Youth’s Screaming Target classic and so discovered reggae. One of the main themes propagated by the Clash was the rise of a multi-cultural Britain; in the group’s early music reggae rhythms jostled with an almost puritan sense of rock’n’roll heritage; as the group progressed, it osmosed and absorbed Latin, blues and early hiphop sounds, with Strummer’s never-less-than-heartfelt lyrics making him a modern-day protest singer, in a tradition stretching back to Woody Guthrie.

Positive light to the darkness of the Sex Pistols, the Clash released an incendiary, eponymously titled first album in 1977, the year of punk, a Top Ten hit. With Strummer at the helm, the group toured incessantly: at a show that year at Leeds University, he delivered the customary diatribe of the times: ‘No Elvis, Beatles or Rolling Stones … but John Lennon rules, OK?’ he barked, revealing a principal influence and hero of his own. The next year, after a night spent at a reggae concert, he wrote what he himself felt was his finest song, ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’, a blues-ballad that opened up the musical gates for the future of the group. In that song, however, was contained the seeds of a paradox that would become more and more uncomfortable for Strummer: one line spoke of ‘new groups … turning rebellion into money’. Through writing such outsider lyrics, he became a millionaire; his problem was one common to many radical figureheads: how do you remain a folk hero when you have succeeded in your aim and are no longer the underdog? Touring the country that summer of 1978, the group’s concerts were shot for a feature film, Rude Boy, directed by David Mingay and Jack Hazan. ‘He already seemed to be suffering terribly from the notion of being Joe Strummer,’ said Mingay. ‘He wasn’t exactly lying back and having a great time. Joe was always full of contradictions, one of which was that he managed to be both ultra-British and anti-British at the same time.’

With London Calling, their third album, the group achieved commercial American success. Sandinista!, a sprawling three-record set, followed. When it became clear that the album was commercial folly, Joe Strummer demanded the return of their original manager, Bernard Rhodes, a business colleague of Malcolm McLaren and someone with whom Mick Jones had always had an awkward relationship. With Rhodes’s sense of wily situationism powering the group, the potential disaster of Sandinista! was turned into a triumph after the group played seventeen nights at Bond’s in New York’s Times Square. The group were the toast of the town, and only a big commercial hit stood between them and superstardom.

That came in 1982 with Combat Rock, a huge international success, selling five million copies. Strummer bought a substantial terrace house in London’s Notting Hill, yet seemed to feel obliged to justify this possession by explaining that it reminded him of the houses in which he used to squat. By 1983, the Clash had begun to disintegrate; first, heroin-addicted drummer Topper Headon was replaced; then, extraordinarily, Mick Jones was fired, Strummer having gone along with Rhodes’s perversely iconoclastic desire to get rid of the founder of the group. New members were brought in, but the Clash finally fizzled out in 1986.

Strummer’s sense of guilt over the sacking of Jones developed to a point of almost clinical complexity. In the late summer of 1985 he asked me to go for a drink with him. After much alcohol had been consumed, he suddenly announced: ‘I’ve got a big problem: Mick was right about Bernie [Rhodes].’ He had finally realized he had been manipulated. He caught a plane to the Bahamas, where Mick Jones was on holiday: an ounce of grass in his hand, he sought out the guitarist’s hotel, and presented him with this tribute, asking to get the Clash back together. But it was too late: Jones had already formed a new group, Big Audio Dynamite; although Joe Strummer ended up co-producing BAD’s second album, his own plans came to nothing.

A familiar figure on the streets and in the bars of Notting Hill, Joe Strummer was mired – as he later admitted to me – in depression. He tried acting, with a passable role in Alex Cox’s Straight to Hell (1987), and a minor part in the same director’s Walker (1987), for which he also wrote the music; he made a much more significant impression in 1989, playing an English Elvis-like rocker in Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train. That same year he released an impressive solo album, Earthquake Weather, and toured. But apart from briefly filling in as singer with the Pogues, he was hardly heard of again. For a time Tim Clark, who now manages Robbie Williams, attempted to guide his career. ‘He was obviously in bad shape,’ Clark told me. ‘He’d turn up for meetings the worse for wear. You could see he was going through a bad time, but you also felt there was probably no one he could really talk to about it.’

After moving out of Notting Hill to a house in Hampshire – he had become worried about his two daughters, he said, after one of them found a syringe in a west London playground – he subsequently split up with his long-term partner Gaby. Remarrying in 1995, to Lucinda Tait, and moving to Bridgwater in Somerset, Joe seemed to find a relative peace. He formed the Mescaleros and began recording again, releasing two excellent albums, Rock Art and the X-Ray Style (1999) and Global A Go-Go (2001), that title a reflection of his interests in world music, about which he presented a regular show on the BBC’s World Service. Strummer was once again touring, incessantly and on a worldwide basis: he was playing to sold-out audiences, with a set that contained a large amount of Clash material. ‘All that’s happening for me now is just a chancer’s bluff,’ he told me in 1999. ‘This is my Indian summer … I learnt that fame is an illusion and everything about it is just a joke. I’m far more dangerous now, because I don’t care at all.’

One of Joe Strummer’s last concerts was at Acton Town Hall last month, a benefit for the Fire Brigades Union. Andy Gilchrist, the leader of the FBU, was apparently politicized after seeing the Clash perform a ‘Rock Against Racism’ concert in Hackney in 1978, and had asked Strummer if he would play the Acton show. That night Mick Jones joined him onstage, the first time they had performed live together since Jones had been so unfairly booted out of the Clash. ‘I nearly didn’t go. I’m glad I did,’ said the guitarist, the poetry of that reunion clear to him.

Bitterly critical that the present Labour government has betrayed many of its former ideals, Joe Strummer was delighted at the show for the firemen; a smile came over his face at the idea that, if only tangentially, his former group was still capable of causing discomfort for those in power. His death, however, comes as a deep shock. After considerable time in the wilderness, Joe Strummer seemed to have reinvented himself as a kind of Johnny Cash-like elder statesman of British rock’n’roll, a much-loved artist and everyman figure. ‘I still thought he’d be doing this in thirty years time,’ said his friend, the film director Don Letts.

2

R.I.PUNK

2002

Christmas Day 2002. Driving through south London, I am wondering if Joe Strummer had known how much people loved him. Pulling up at traffic lights, I glance to my left; there, spray-painted across a building in large scarlet letters, seems to be some sort of answer to my meditations: JOE STRUMMER R.I.PUNK. I call Mick Jones and leave a message, telling him what I’d seen. Joe’s funeral, eight days after he died, polarized all my thoughts and feelings. The following day I wrote this:

Monday, 30 December 2002

The sky is a slab of dark, gravestone grey; rain belts down in bucketfuls, leaving enormous pools of water on the roadside: Thomas Hardy funeral weather. Ready for the funeral’s 2.00 p.m. kick-off, I find myself at the entrance to the West London crematorium on Harrow Road. A voice calls to me from one of the parked cars: it is Chrissie Hynde and Jeannette Lee (formerly of PIL, now co-managing director of Rough Trade, a punk era girlfriend of Joe). Chrissie is clearly in a bad state. ‘Not great,’ she answers my question.

On the main driveway I bump straight into the music journalist Charles Shaar Murray and Anna Chen, his girlfriend: he looks fraught. It is pouring with rain. I take a half-spliff out of my jacket pocket and light it, take a few tokes, and hand it to Charlie. Out of the hundreds of hours I had spent with Joe I don’t think I had been with him on a single occasion when marijuana had not been consumed, so it seems appropriate, even important, to get in the right frame of mind to be with him again.

The spliff is still burning when I see massed ranks of uniformed men. Not police, but firemen, two ranks of a dozen, standing to attention in Joe’s honour. With Charlie and Anna, I walk between them. Standing under the shelter of a window arch I see Bob Gruen, the photographer, and walk over to him. We hug. Then Chrissie and Jeannette arrive; Jeannette and I hug. Soon Don Letts also arrives. I roll him a cigarette.

Suddenly it seems time to walk inside the building, into the main vestibule. That’s where everyone has been waiting. I see Jim Jarmusch, who directed Joe in Mystery Train, Clash road manager Johnny Greene, and – next to him – the stick-thin, Stan Laurel-like figure of Topper Headon. We hug; there is a lot of hugging today. Against the wall I see an acoustic guitar, covered in white roses, really beautiful. In its hollowed-out centre is a message: R.I.P. JOE STRUMMER HEAVEN CALLING 1952–2002. A large beatbox, next to it, is similarly covered in white roses. All the seats in the chapel are full. I find a gap against the rear wall. A lot of people are snuffling.

Then the sound of bagpipes sails in through the door, lengthily, growing nearer. (Later I learn that the music is The Mist-covered Mountains of Home, also played at the funeral of President John F Kennedy.) At last Joe’s coffin slowly comes in, held aloft by half a dozen pallbearers. It is placed down at the far end of the chapel. Keith Allen, the actor and comedian, steps forward and positions a cowboy hat on top of it. There’s a big sticker on the nearest end: ‘Question Authority’, it reads, then in smaller letters: ‘Ask Me Anything’. Next to it is a smaller sticker: ‘Vinyl Rules’. On the sides of the coffin are more messages: ‘Get In, Hold On, Sit Down, Shut Up’ and ‘Musicians Can’t Dance’. Around the end wall of the chapel are flags of all nations. More people are ushered in, like the kids Joe would make sure got through the stage-door at Clash gigs, until the place is crammed. In the crush I catch a glimpse of Lucinda, Joe’s beautiful widow: she carries herself with immense dignity but – hardly surprisingly – has an aura of almost indescribable grief, pain and shock. People are standing right up by the coffin. The aisle is packed: suddenly a tall blonde woman, looking half-gorgeous, a Macbeth witch, is pushed through the throng, to kneel on the stone floor at the front of the aisle – it’s not until later on that I realize this is Courtney Love.

The service begins. I don’t know who the MC is, a man in his late fifties, a vague cross between Gene Hackman and Woody Allen. He’s good, tells us how much love we are all part of, stresses how honoured we are that our lives were so touched by Joe, says that he’s never seen a bigger turn-out for a funeral. (There is a sound system outside, relaying the proceedings to the several hundred people now there.) Then he says we’ll hear the first piece of music, and we should turn our meditations on Joe: it is ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’.

Paul Simonon gets up to speak. He tells a story about how when the Clash first formed in 1976, he and Joe had been in Portobello Road, discussing the merits of mirror shades, as worn by Jimmy Cliff in The Harder They Come. If anyone showed you any aggro while you were wearing such a pair, Joe decided, then their anger would be reflected back at them. Immediately he stepped into a store that sold such sunglasses. Paul didn’t follow: he was completely broke, having been chucked off social security benefits; Joe, however, had just cashed that week’s social security cheque. He came out of the store wearing his brand-new mirror shades. Then they set off to bunk the tube fare to Rehearsal Rehearsals in Camden. As they walked towards Ladbroke Grove tube station, Joe dug into his pocket. ‘Here,’ he said, ‘I bought you a pair too.’ Although Joe was now completely broke and with no money to eat for three days, he’d helped out his mate. This story increases the collective tear in the chapel.

Maeri, a female cousin, gets up to speak. Joe’s mother had been a crofter’s daughter, who became a nurse and met Joe’s father in India during the war. Joe’s dad liked to have a great time: a real rebel himself, it seems, not at all the posh diplomat he has been made out to be, a man who pulled himself up by his bootstraps. We are told a story about Joe as a ten-year-old at a family gathering: he is told that he can go anywhere but ‘the barn’; immediately he wants to know where ‘the barn’ is. Then another female cousin, Anna, reads a poem, in English, by the Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean.

Dick Rude, an old friend of Joe’s from LA who has been making a documentary about the Mescaleros, speaks. Keith Allen reads out the lyrics of a song about Nelson Mandela, part of an AIDS charity project for South Africa organized by Bono of U2, that Joe had just finished writing. A Joe demo-tape, just him and a guitar, a slow blues-like song, is played. And the Mescaleros tune, ‘From Willesden to Cricklewood’. The MC suggests that as we file past the coffin to leave, we say a few words to Joe. ‘Wandering Star’ begins to play. ‘See you later, Joe,’ someone says. Yeah, see you later, Joe.

After the extraordinary tension that has built up to the funeral since Joe’s death eight days ago – my sleep is disturbed and troubled the night before the service – it feels like a release when the service concludes. (I have felt Joe around ever since he passed on: Gaby, his former long-term partner, has felt the same thing, she tells me on the phone the previous Friday, and I tell her that a mystic friend of mine has spoken of Joe ‘ascending’ very clearly – according to Buddhism, there is a period of forty-eight days following a death before the soul returns in another form; Gaby feels the same, saying she feels he is very at peace; job done, on to the next incarnation. Until someone reminds me, I have forgotten that Gaby has had plenty of experience of death, her brother having committed suicide while she was still with Joe – as his brother did.) Somehow I expect almost a party atmosphere outside the chapel, with the sound system maybe blaring out some Studio One. But everyone is wandering around in a daze. The wake is being held at the Paradise bar in nearby Kensal Rise.

Outside the Paradise a bloke in a suit and black tie asks if I have any change so he can park his car. He looks familiar; it is Terry Chimes, the original Clash drummer, who had resigned from the group after making the first album, leaving the way open for Topper Headon. Terry is now a superstar of chiropractry, giving seminars on the subject.

The bar is packed with people and a grey atmosphere of grief. I see Lucinda and hold her for a moment. Simultaneously she feels as frail as a feather and as strong as an oak beam. But she is clearly floating in trauma. I tell her how sorry I am, and as I speak my words feel inadequate and pathetic. From a stage at one end speakers are batting out reggae. The pair of pretty barmaids are struggling with the crush. I am handed a beer, which I down, pushed into a corner. I see a woman with a familiar face: Marcia, the wife of Jem Finer, effectively leader of The Pogues – I used to enjoy spending time with them at evenings and parties at Joe’s house when he still lived in Notting Hill. I am incredibly flattered by what she says to me. She says, ‘Joe always used to say that you were the only journalist he trusted. And he said he loved you as a friend. He really loved you.’ I am unbelievably touched by this. I want to talk to her more, but she is clearly looking for someone. I nearly burst into tears when what she has said fully registers with me. (I’m not unusual in being in such a state: all around me I see men putting their hands to their eyes, sobbing for a few moments.) Later Jem Finer, Marcia with him, deliberately seeks me out and tells me this again, both of them together this time.

Next to the cloakroom I find a couple more rooms, where food has been laid out. I grab a plate: smoked salmon, feta cheese salad, pasta – good nosh. And sitting down I find a middle-aged woman. The sister of Joe’s mum, and a great person, Sheena Yeats now lives in Leeds, where she teaches at the university. She’s very Scottish, however: ‘Well, this is the best funeral I’ve ever been to,’ she burrs, with a smile. ‘Joe would have really appreciated it.’ She tells me how Joe had been up to Scotland a month ago, to a wedding, and that he had been in touch with everyone in his family recently. She reminds me that Joe’s mum Anna had passed on in January 1987. ‘Although he chose to call himself Joe, because it was such an everyman name, his real name was John, a name with the common touch,’ she explains.

Bob Gruen tells me how Joe had been in New York a couple of months ago, in some bar, leading the assembled throng in revelry and having a great time. Seated nearby is Gerry Harrington, a Los Angeles agent who had guided Joe’s career when he was working on Walker and Mystery Train and releasing 1989’s Earthquake Weather. Joe had written a song for Johnny Cash last April, at Gerry’s house in LA, entitled ‘Long Shadow’: he plays it for me on an I-Pod, an extraordinary valedictory work that could have been about Joe himself, with lines about crawling up the mountain to the top.

I talk to Rat Scabies, former drummer with the Damned. He tells me he and Joe had been working together in 1995 on the soundtrack of Grosse Pointe Blank, but that they fell out over that hoary old rock’n’roll chestnut – money. ‘I was stupid,’ he admits. ‘I thought I knew everything from playing with the Damned. But working with Joe was like an entirely new education. He understood how to trust his instincts and go with them every time. I couldn’t believe how fast he worked.’

I run into Mick Jones. He puts his arms around me and kisses me on the cheek. We hold each other. He tells me how he’d loved the message I’d left on his voice-mail after seeing the JOE STRUMMER R.I.PUNK graffiti on Christmas Day; it had touched Mick as deeply as it touched me. He tells me how great the Fire Brigades Union have been, and that the police have behaved similarly. At the Chapel of Rest where Joe had been laid in Somerset a sound system had blared out 24-7. When the police came round in response to complaints from neighbours, and were told it was Joe who was lying there, instead of telling them they must turn down the music they responded by placing a permanent two-man unit outside the chapel: a Great Briton getting a fitting guard of honour, an irony Joe would have appreciated as his mourning bredren consumed several pounds of herb.

Pearl Harbour, Paul’s ex-wife, is there, talking to Joe Ely, the Texan rockabilly star who had often played with the Clash. She tells me how this trip has brought closure for her by bringing her back to what, she admits, was the happiest time in her life.

A moment later Tricia – Mrs Simonon – comes over as Pearl departs and proceeds to tell me how the absent Clash manager Bernie Rhodes had been contacted and invited to come to the funeral, but after the usual over-lengthy conversation it was impossible to discover what Bernie really felt or thought. ‘It seemed that he was more intent on getting on to the next agenda, which was that he desperately wanted to be invited to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction for the Clash next March. What he didn’t realize was that it was already decided that he would be invited.’

‘I always had a soft spot for Joe,’ Bernie later told me. ‘But I couldn’t go to the funeral because I didn’t like the people he was hanging around with.’

Joe and Mick had both wanted a re-formed Clash to play at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction. But the one refusenik? Paul Simonon, painter of Notting Hill. Trish admits that the last communication Paul had from Joe was on the morning that he died. Joe sent Paul a fax – he loved faxes, hated e-mails – saying, ‘You should try it – it could be fun.’ Paul, however, was adamant that the group shouldn’t re-form for the show.

Never too computer-literate, Joe wrote on a typewriter to the end. (Lucinda Mellor)

Next I find myself in a long conversation with Jim Jarmusch’s partner, Sara Driver, who commissioned Joe to write the music for When Pigs Fly, a film she made in 1993, starring Marianne Faithfull, that suffered only a limited release after business problems, and Bob Gruen’s wife Elizabeth. Jim is sitting next to us, deep in conversation with Cosmic Tim, a mutual friend of Joe and myself, from completely separate angles of entry. I had walked into the main upstairs bar as Cosmic Tim was standing on the stage with a microphone. It was the usual stuff that had gained him his sobriquet, and I groaned inwardly. ‘And this man Baba had been to the mountains of Tibet and lived there for twenty-five years, meditating.’ Other people in the packed crowd were groaning too (‘Get on with it.’). But then Cosmic Tim turned it around: ‘And one day when he returned to London, I was walking down Portobello Road with Baba when I see Joe walking towards us. I cross the road, and Baba and Joe look at each other. Suddenly, Baba calls out, “Woody!” (Joe’s nickname from The 101’ers.) And Joe looks up and shouts, “Baba!”’ According to Tim, Baba and Joe had known each other at art college. At length Sara, Elizabeth and myself discuss the state of depression in which Joe was regularly mired, and that most of the tributes to him that day are utterly omitting. Sara says how Jim used to refer to him as ‘Big Chief Thundercloud’. She also tells me how Joe had an enormous crisis when he was on tour in the States singing with the Pogues: he had fallen deeply in love with a girl and wanted to leave Gaby for her. Although he didn’t, in some ways it was the end of his relationship with the mother of his children. (This was a period when I remember Joe seemed even more in turmoil than usual, an air of great anger about him.)