Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Cheryl: My Story»

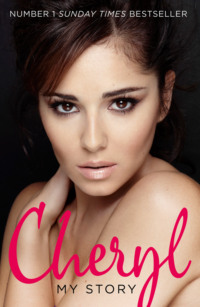

Cheryl

MY STORY

Epigraph

Keep Calm and Soldier On.

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1. ‘Follow your dreams, Cheryl’

2. ‘You need to get your head out of the clouds’

3. ‘Open up now or we’ll take your kneecaps off’

4. ‘I’m so proud of you I could pop’

5. ‘You’re arresting me?’

6. ‘Ashley treats me like a princess’

7. ‘Will you marry me?’

8. ‘You’ve come a long way, Cheryl!’

9. ‘Something happened … but I don’t know what’

10. ‘Everyone loves you. You’re a star. Well done!’

11. ‘I just want to be a wife’

12. ‘Unfortunately, you’re going to be number one next week’

13. ‘Even if it kills me, I want to know it all’

14. ‘I’m divorcing you’

15. ‘Yes! This is what I live for’

16. ‘You’re tryin’ to kill me!’

17. ‘Do they not think I’m a human being?’

18. ‘Cheryl, I know you’re laughing but this is really bad’

19. ‘Get me into my music again!’

Epilogue

Picture Section

About the Author

Picture credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

Rachel Murphy – thank you for helping me write this. We’ve had laughter and tears, and I’m THRILLED with the result! Ha ha.

Carole Tonkinson, Victoria McGeown, Anna Gibson, Georgina Atsiaris, Steve Boggs and everyone at HarperCollins – thank you all so much for making this such an easy and enjoyable process.

Solomon Parker, Eugenie Furniss and Claudia Webb at WMA – thank you for giving me this opportunity and starting me off on the right path.

Richard Bray and Ailish McKenna at Bray & Krais.

Rankin.

Seth, Sundraj, Lily and Garry – thank you!

Thank you to my team, my loved ones and all the amazing people I have in my life – and lastly to all the arseholes who have crossed my path and made it so colourful!!!

Prologue

‘Can I have your autograph and a picture?’

I was totally stunned. Was this person really here, asking me to sign my name and pose for a photo?

‘Well … can I?’

The woman was staring at me hopefully, holding a camera up and pushing a bit of paper towards me.

‘No, absolutely not,’ I stuttered. I was flabbergasted. Disgusted, actually.

This wasn’t a fan at a Girls Aloud concert or someone waiting outside the X Factor studios. The woman was a cleaner at the London Clinic where I was being treated for malaria.

I’d literally nearly died just days before, and now I was lying in bed looking and feeling so weak and ill, and trying to get my head around what the hell had happened to me. The cleaner stuffed the camera in her apron pocket and looked quite put out, as if I’d turned down a perfectly reasonable request.

Derek was horrified, and he leapt up and showed her the door. He’s one of the most kind and sensitive and gentlemanly men I have ever met, but I swear from the look in his eyes he wanted to kill that woman.

I stared at Derek in disbelief. How had my personal life got so tangled up with my job and my fame that other people no longer treated me like a human being?

‘Am I going to die?’ I’d asked a nurse on my first day in intensive care. There was a pause before she told me plainly: ‘There’s a possibility.’

Her words didn’t shock me. I was so exhausted that I actually felt relieved. ‘If I am dying, just hurry up and make it happen,’ I thought. ‘I’m too tired. For God’s sake, make this end.’

I spent four days in intensive care at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases and was now out of danger, but I was still very ill. My body felt incredibly weak and I’d been drifting in and out of sleep and consciousness for days. My head was heavy and foggy and it was so uncomfortable even just to lie down.

‘I’ve survived,’ I thought in the moments after the cleaner was shown out of the room.

‘But what’s happened to me? Who am I?’

Being in hospital is hell. All you can do is lie there and think. I couldn’t walk. I was stuck in bed with machines bleeping all around me, trying to make sense of how and why I was here, and what my life had become.

My life was crazy, and it had been that way for a long time. The way the cleaner treated me was just the latest proof of how mad it was. She didn’t stop to think that I was a living, breathing woman who had been at death’s door. I’d been asked for pictures at inappropriate moments many times before, but this one topped the lot in terms of cheek and weirdness.

I shut my eyes and thought back to earlier that day, when I’d been taken for a lung scan. I was dressed in a hospital gown and I had filthy hair that was so greasy it looked like I was wearing a cap with long pieces of hair sticking out from under it. I hadn’t showered or been out of bed for a week and my face was yellow with jaundice, but in that moment I didn’t care. It was just amazing to be on the move instead of lying in bed, attached to tubes and machines. As I was wheeled down the corridor I could feel the air blowing through all the hair that wasn’t stuck to my head. I honestly felt like a girl in a shampoo advert, wafting my hair about in the breeze.

All of a sudden a little girl pointed at me excitedly.

‘I swear that’s Cheryl Cole!’

Her words changed my mood in a heartbeat. As soon as she spoke I didn’t feel free any more. I felt exposed and extremely uncomfortable.

‘Take me back to me room, please,’ I immediately said to the nurse.

I was so taken aback that I’d been recognised, in here. The hospital should have been a haven for me, but it wasn’t. I didn’t even look like me, yet the girl still recognised me and she must have been poorly too. I felt mortified. I had no privacy, absolutely nowhere to hide. That’s how I felt.

In hindsight I can see the funny side of that story and I don’t blame the young girl for reacting the way she did. I was in a very dark place then, though, and I just couldn’t see any light at all. When the cleaner asked for my autograph and a picture not long afterwards, it was like a light going on.

I had grown up wanting to be a pop star, but I had never anticipated this level of fame. Nobody could have prepared me for this. I’d followed my childhood dream and I’d achieved it, and so much more. I should have been happy, but I felt like my life was not my own at all, on any level, not even when I was recovering from a serious illness. It was out of my control, and as I lay in my hospital bed I could see that I had to make changes, or I would end up going completely crazy.

It’s more than two years since I had malaria, and now I feel sure I had it for a reason. It’s almost as if it was God’s way of forcing me to stop and get off the rollercoaster ride my life had become. It made me take a good look at myself, and that is what I have done.

It’s only very recently that I’ve felt strong enough to talk about what’s gone on in my life, and to start to put things in perspective.

I actually feel grateful for everything that’s happened, the good and the bad, because my life has been amazingly colourful and eventful. Incredible, in fact. Now I finally feel ready, and strong enough, to open up my heart and tell you all about it.

1 ‘Follow your dreams, Cheryl’

If anyone had asked me to describe my life when I was a little girl growing up in Newcastle, this is what I would have told them:

I’m seven. We live in a massive house in Byker. Little Garry sleeps in with me mam and dad, I share a room with our Gillian and Andrew, and we all have bunks. Joe, who’s our big brother, has a room all to himself. He’s a big teenager, seven years older than me, and so I hardly ever see him. One Christmas, me and Gillian definitely seen Santa though, and at Halloween we definitely seen a witch. I like magical things, and the Chronicles of Narnia is one of me favourite TV programmes. Me dad plays the keyboard and is always sayin’ to me: ‘Go on, Cheryl, I’ll play something and you make up the words.’ Me Nana made a tape of me when I was three. She wrote on it: ‘Little Cheryl Singing’ – and I was so proud. Top of the Pops is always on the TV and I tell me dad: ‘I’m gonna be on there when I’m bigger!’

‘Cheryl, sweetheart,’ he says. ‘You’ll need to get a proper job when you get big!’ He works really hard as a painter and decorator and me mam stays home and looks after all us kids. She tells me, ‘Follow your dreams, Cheryl. Do what your heart tells you.’ Me mam’s very soft and gentle but she tells me I’m too soft!

‘That guy’s just punched him senseless!’ I heard me dad say one night when he was watching a boxing match on the telly. I cried all night long, thinking to meself, ‘When’s that poor man gonna get his sense back?’ ‘Honest to God, Cheryl, you need to toughen up,’ me mam said.

Gillian’s four years older and Andrew is three years older than me. Everyone says they’re like two peas in a pod, so close in age they’re like twins. I was four when our Garry was born and he’s the baby of the family. Me, Gillian and Andrew like playing fish and chip shops in the back garden. We use big dock leaves for the fish, me dad’s white paint is the batter and the long grass is the chips. Andrew’s always telling us daft stories that can’t be true and making us laugh. Me and Gillian make up dance routines and pretend we’re in Grease or Dirty Dancing, but Gillian’s a proper tomboy. She went to disco dancing classes once but didn’t like them at all. I absolutely love dancing. I do it all; ballet, modern, jazz and ballroom after school, and on the weekend. I’ve done it since I was three and I’ve been in shows and pantos and all that. ‘Show us your dancing, Cheryl,’ everyone always says, and so I do, all the time. I love it.

When I look back on my childhood through adult eyes I feel very grateful to my mam and dad for giving me such happy memories, especially as I know now that it wasn’t easy for them.

The ‘massive’ house I remember was in fact a really tiny, box-like council house that must have been really cramped with seven of us under the one roof. There wasn’t a lot of money, but as a little girl I never remember feeling poor. I always had Barbie dolls to play with and didn’t care that they were second-hand and out of fashion, and I always got presents I treasured at Christmas, like the one year when I got a sweet shop with little jars you could fill up. I absolutely loved it.

For our tea we ate food like beans on toast, corned beef hash or grilled Spam. A Chinese takeaway was a treat because we couldn’t afford it, but we were no different from anybody else on our estate. Mam would buy us things from catalogues and save up to pay the bill at the end of the month. I remember the end of August was always a nightmare because my mother had to get everyone kitted out with new uniforms and pencil cases, all at the same time. I could feel the tension in the house, but we always got through it. Sometimes we wore hand-me-down clothes, but that was completely normal. Neighbours and relatives passed things on; that’s what everybody did. Pride is a massive thing for Geordies and Mam made sure that, one way or another, we always looked presentable and we never went without.

I’ve had to ask my mam to fill me in on some of the details about my really early years, especially with all my dancing, as I was too young to remember a lot of it. I also thought it might be nice to give my mam, Joan, the chance to tell this part of the story herself, and this is what she told me when I started writing my book.

What Mam remembers …

One of me friends told me there was a local bonny baby competition and that I should enter you because you were such a pretty baby. You really were a pretty baby, with very dark hair and lots of it.

I happened to walk past Boots one day in the local shopping centre and saw the competition advertised. I thought, ‘why not?’, took you in for a picture and then forgot all about it … until I found out you’d won it. Family and friends encouraged me to enter you into other similar things. You won every time and eventually, through winning competitions, a model agency approached us and asked if they could take you on. ‘Why not?’ I thought again.

When you were about three years old one of me friends said, ‘Let’s take the kids to disco dancin’.’ She told me there was a class on opposite the Walker Gate metro station, run by a lady called Noreen Campbell. ‘Why not?’ I found meself saying yet again. You loved dancin’ at home. The boys did things like karate and trampolining but I tried to give you all a chance to do things I thought you’d enjoy, and I knew this was more your thing. When we got there Noreen told us we’d been mistaken. She didn’t teach disco – this was a ballet, tap and ballroom class. You had a go and loved it, and from that very first day Noreen started telling me you were really good at all types of dancing. ‘She’s got real talent, something special,’ she told me. You couldn’t get enough of it, and as soon as you were old enough Noreen entered you for dancing competitions, which you always won.

After that she put you up for auditions for pantomimes, theatre shows – everything. You were Molly in a production of Annie when you were about six, at the Tyne Theatre, and at the same time the model agency was putting you up for all sorts of fashion shows in shopping centres, or for catalogue work and adverts. I was asked if Garry could go on the books of the model agency too as he was always with us, and the pair of you appeared in a British Gas TV advert together. You did one for the local electricity board and a big furniture store, too. As long as you were happy I took you along and let you do whatever was on offer, and you always loved it, posing very naturally and even suggesting different poses for the camera, which made us all laugh.

Stage school was another thing you did for a time. I’ve always been of the opinion that in life you have to give anything a go and whenever another new thing was suggested I’d always let you try it to see if you liked it. You won a ‘Star of the Future’ competition and a ‘Little Miss and Mister’ contest run by the Evening Chronicle, and you were always very proud of yourself when you appeared in the paper. Any prize money you got from winning competitions, or fees from modelling, all went back into costumes or whatever else you needed, so you kept yourself going. Your brothers and sister didn’t mind me taking you places all the time. They loved what you did and were forever asking you to show them and their friends your latest dance routine or pictures.

When you were about eight or nine we were encouraged to try out another ballet school run by a lady called Margaret Waite, who had a really good reputation. It was Margaret who suggested you should try out for the Royal Ballet’s summer school, and I know you remember all about that. All I’ll say is that I was happy for you to do it, and I was happy for you to give up the ballet. ‘What do you want, Cheryl?’ I would always ask, because you knew your own mind from a very young age. You had a lot of confidence as well whenever you were performing. I don’t know where it came from, especially because at home you were very soft and terribly sensitive. Our first house at Cresswell Street in Byker was always like an RSPCA rescue centre because you’d bring home pigeons with broken wings or stray cats that usually turned out to not be strays at all. Sometimes they just rubbed up against your leg in the street and you brought them home, feeling sorry for them and trying to adopt them. You worried yourself far too much about everything and everybody else, all the time. I remember telling you, right from when you were a very small girl: ‘Life is tough, Cheryl. You need to toughen up.’

My mam is right. Of all my dancing experiences I do remember the whole Royal Ballet episode clearly. Margaret Waite was a really amazing dancer who’d had a brilliant career with the Royal Ballet herself before she set up her school in Whitley Bay. It was about fifteen miles from where we lived and twenty-odd stops away on the metro, but it was the place to go if you were really into ballet. Margot Fonteyn was my heroine and I couldn’t get enough of my ballet classes. I did every competition going and always managed to win.

‘You’re excelling,’ Margaret told me one day. ‘At nine you’re a bit too young, but I want you to apply to the Royal Ballet summer school. It’s extremely hard to get in but I think you’re good enough.’

I told my mam, who took me along for the audition somewhere in Newcastle. Mam didn’t ask any questions, and I don’t think I fully understood what I was applying for. I just put on my favourite tutu, did my best on the day, then went home to play.

One of my favourite games at that time was to pretend I was running a beauty salon. I’d convince Gillian I was really good at doing make-up and then I’d put mascara and blusher on her. Sometimes I’d even persuade my little cousins – the boys included – to let me put eye shadow on them, or lipstick. I’d also tell them all kinds of tales, like the time I convinced one of my really young cousins that the Incredible Hulk lived round the corner. When my mother found out what I was up to she went mad.

Dad was always much stricter than my mam, and I knew I had to behave myself much better when he was in the house. One day I remember my dad looking very serious, and I wondered if I was in trouble about something, but I didn’t know what.

‘Me and your mam need to talk to you,’ he said. ‘Sit yourself down, Cheryl.’

He took a deep breath and said: ‘You’ve been offered a place at the Royal Ballet …’

My heart leaped in my chest, but before I could jump up and cheer Mam interrupted. ‘We’re really proud of you, Cheryl. You’ve done really well and we know you’d love to go. But the thing is …’

Dad finished the sentence, and my heart sank like a stone. ‘We can’t afford to send you. I’m sorry, sweetheart. It’s such a lot of money and we just haven’t got it …’

I ran up to my room and cried, hugging my pillow. It had no cover on it and a jagged line of red stitching down one side where I’d sewn it back together really badly, probably after whacking Gillian or Andrew with it in a fight. I always held onto that old pillow whenever I got upset about something, and this felt like the worst thing ever.

Mam appeared at the door. ‘Cheryl, we’ll see what we can do. Things are never as bad as they seem. You’ve got Gimme 5 again next week. Put your chin up.’

Gimme 5 was a Tyne Tees kids TV programme I’d appeared on a couple of times with a bunch of kids from the dance school. I tap-danced with Jenny Powell once and hit her in the face by accident, and another time I showed off my ballroom dancing skills, doing the rumba.

‘Get her back on!’ I heard one of the television people say. ‘She’s hilarious!’

I think this was because when I was ballroom dancing I really got into it and pulled all these crazy faces. I can see now how funny I must have looked because I was only nine years old yet I was trying to look all sensual and sexy, like I thought ballroom dancers should. I didn’t even realise I was doing it at the time. I just really felt the music like that, and being on the TV felt normal to me, so I just let myself go.

I can remember going round some of the local old peoples’ homes with the dance school too, and the pensioners would howl laughing when I pulled those faces. I loved it. It encouraged me, because I felt like I was really entertaining them.

‘You’ll never guess what, Cheryl,’ my mam said one day, ages after my dad had delivered the bad news. ‘We’ve managed to find all the money after all. You can go to the Royal Ballet!’

I screamed in excitement and gave our dog Monty a big hug. Monty was a long-haired Dachshund who hated every one of us kids but was obsessed with my mother. He wriggled away from me as fast as he could, as usual, but for once I didn’t care. I grinned at my mam and said thank you over and over again. This meant I’d be going down to London for a whole week in the summer holidays, to be taught by some of the best ballet teachers in the world.

I knew my mam and dad had been pulling out all the stops but I hadn’t wanted to get my hopes up. I found out later they’d done a newspaper story to help raise the money they needed. I think the whole thing cost about £500 but they’d been at least £200 short. The paper sponsored me, and I ended up doing a photoshoot and a story to say thanks to everyone who’d helped.

It was August 1993 by now and I’d turned ten in the June. I’d never been to London before. In fact, I had not set foot out of the North East. We never had a holiday and all my life had taken place in Newcastle. I thought the whole of the country must be the same as it was on our estate, and I assumed everyone spoke like me because I didn’t know any different.

‘Gals, I will teach you all how to cut an orange into neat segments so you can eat it nicely,’ one of the prim and proper ladies at the ballet school told us on the first day.

She had a very tight bun in her hair and didn’t look like she’d ever cracked a proper smile in her life.

That’s my first memory of being there. Mam had dropped me off with a tiny little suitcase and I was staying for a week all by myself, at this posh place called White Lodge, in Richmond Park.

We’d been given salad and fruit for lunch on the first day, which put me off right away. ‘I want chips and beans,’ I thought when I saw the lettuce leaves and oranges. I wasn’t even used to the word ‘lunch’. As far as I was concerned you ate your dinner in the middle of the day and had your tea at night. What’s more, when you ate an orange you peeled it with your fingers and the peel would magically disappear when you left it on the table or dropped it on the floor.

I caught other girls giving me sideways glances whenever I spoke. Nobody sounded like me, and I felt out of place. They were all very well put together too, in clothes that were actual makes, while mine were from C&A or the Littlewoods catalogue.

‘Cheryl Tweedy, please step forward.’ We were in a grand hall, and I was being asked to show off a little routine.

I could sense the other girls giving me funny looks and it put me right off because I was used to being super comfortable and completely fitting in, whatever I did.

‘What?’ I said when the teacher said something I didn’t quite hear. ‘Pardon,’ she corrected snootily. ‘We always say “pardon” not “what”, don’t we, gals?’

I thought to myself, ‘That’s funny, none of me teachers at school ever tell me that.’

We slept in a big dormitory and I hated it. I just wanted to go home and climb into my bunk bed. Even if Andrew was there fighting with me or trying to dangle me off the top bunk like he sometimes did for a laugh, I would have felt much happier than I did here.

I wrote a letter home and said, ‘Tell Monty I miss him.’ Really, I missed everything and everyone back home but I didn’t want anyone worrying about me. I missed the noise and the chaos in our house, I missed bumping into my aunties and uncles and cousins who all lived two minutes away from our house, and on Sunday I really, really missed having a roast dinner at my Nana’s, knowing everyone else would be there as usual. Sometimes it was bedlam, but I still would have swapped places in a flash.

One time Andrew and Gillian got caught smoking behind my Nana’s settee. They’d taken her ashtray and lit the old cigarette ends. My dad saw the smoke coming from behind the settee and went crazy. Gillian and Andrew were only small at the time so it must have been quite a few years before, but memories like that came back to me as I lay in my bed in the dormitory, feeling a million miles away from home.

I thought about my school as well. I went to St Lawrence’s Roman Catholic Primary, even though we weren’t Catholics. It was just down the road from our house and had a very good reputation; that’s why Mam and Dad sent us there. I loved it, and I’d even asked Mam if I could take my Holy Communion like the other girls because I wanted to wear the white dress and gloves. ‘You can decide your own religion when you’re old enough,’ Mam told me. Our head teacher was a nun and I felt peaceful in that school, and like I belonged. I had a go at playing the cello, the clarinet and the flute. It was fun and easy and not strict.

Mam would walk us to school every morning and I remember one day she suddenly made us stop in the street.

‘Look! There’s a hedgehog stuck down there!’

I peered down and saw this huge hedgehog completely wedged at the bottom of an open manhole. Mam made us run home and fetch a bucket and spade and rubber gloves, which we used to rescue it. We then took the hedgehog to the park to set it free. We were late for school but my mam explained what had happened and we didn’t get into trouble.

Joe was the one who usually got into trouble, not the rest of us. There’d often be a knock on the door and a neighbour would be standing there fuming and telling my mam: ‘Your son’s bashed my son.’

He was just like many of the other teenagers in the neighbourhood and Mam would wallop Joe when he misbehaved, even though she is only four-foot ten. I couldn’t remember a time when my big brother wasn’t taller than her, in fact. Mam was pretty strong for her size and we all got smacked by my mother when we were naughty, usually on the back of the legs. It always stung like mad and I remember we’d threaten to phone ChildLine whenever that happened, though we were never serious.

My dad would be more likely to shout when things went wrong, like the time when Joe broke his leg after getting drunk and falling down an open drain. Dad exploded and shouted really loudly, and I had to put my hands over my ears.

It was chaos a lot of the time, but it was home, and it was all I knew. Lying in this neat and quiet dormitory, surrounded by girls who wore Alice bands and spoke like the Queen, made it seem like Newcastle was in another world, or even another universe.

On my last day at the Royal Ballet my mam came to watch the farewell presentation. I was that happy to see her sitting there amongst all the other mothers that I couldn’t help waving and grinning at her. All the rest of the girls stood like little statues, as we’d been told to do, but I was so excited I just couldn’t help myself. Even when Mam tried shaking her head and mouthing at me nervously to stop, I carried on.

‘How could they all stand there like that?’ I asked her later that day, when we were finally heading home.

I’d skipped out of the gates as fast as I could, absolutely delighted to be getting out of that stuffy place.

‘It’s called etiquette,’ Mam said.

‘Pardon?’ I replied, not for the first time that day. I could see that word was annoying my mam but I couldn’t help using it, because it had been drummed into me all week.

‘Cheryl, if you pardon me once more I swear I’ll knock your block off,’ Mam replied. She wasn’t joking, either, but I was so happy to be back with my mam. It had felt like I’d been away forever, and I just wanted to get back to everything I knew and loved.

‘I want to give up ballet,’ I announced just a few days later, when I was eating a packet of crisps at home in front of the telly. ‘It’s not fun any more.’

‘That’s fine, Cheryl,’ Mam said. ‘If you don’t like it you don’t have to do it. That’s the end of it.’

I didn’t give up dancing altogether. I still did some other classes, but not as regularly, and definitely not as passionately.

I was in my last year of primary school by now, and so it was inevitable that my life was changing in other ways too. I was about to leave St Lawrence’s and go to Walker School. I was growing up, and it was a little bit daunting, but exciting too.

There was also another big change about to happen in my life, although this was one I definitely didn’t see coming. I was eleven years old; I can remember the day it happened like it was yesterday.

‘Tell me the truth! What the hell is happening? What’s going on?’

It was Andrew, and he’d burst in the front door in a terrible rage. I’d never, ever seen him in such a state and he started ranting and raving at my mam and dad. They both looked really worried and my heart started beating super fast in my chest.

‘I’ll explain it,’ Mam said. Her eyes looked sad and she had deep frown lines in her forehead. Dad had gone all quiet, which panicked me, as normally he’d have gone mad at Andrew for shouting and screaming like that.

The atmosphere felt much more chaotic than I’d ever known. It was like a big bomb had gone off. I didn’t know how or why, but it felt like another bomb was going to explode any moment.

‘Is Dad my real dad?’ Andrew screamed in my mam’s face. I swear the clock stopped for a second when he said that.

‘I want to know the truth – all of it!’

Andrew was shaking now, and shouting that someone had told him in the street that my dad wasn’t his real dad. He’d asked my aunty if it was true.

‘How do you know?’ my aunty had said. ‘You’d better ask your mam!’

Andrew was going so berserk that he looked like a crazy person, but however mad he looked, this was sounding horribly realistic.

I was listening to every word, trying to make some sense of it all, but I wasn’t sure what the truth was, or why this was happening. Gillian was in the room, and she was going mental now too.