Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «A Dark Secret»

Copyright

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences. In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperElement 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Casey Watson 2019

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

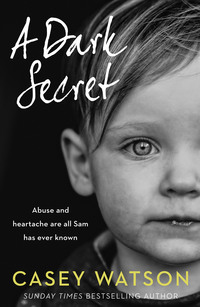

Cover image © Clive Nolan/Trigger Image (posed by model)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Casey Watson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780008298616

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008298654

Version: 2019-03-28

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Contents

5 Dedication

6 Acknowledgements

7 Chapter 1

8 Chapter 2

9 Chapter 3

10 Chapter 4

11 Chapter 5

12 Chapter 6

13 Chapter 7

14 Chapter 8

15 Chapter 9

16 Chapter 10

17 Chapter 11

18 Chapter 12

19 Chapter 13

20 Chapter 14

21 Chapter 15

22 Chapter 16

23 Chapter 17

24 Chapter 18

25 Chapter 19

26 Chapter 20

27 Chapter 21

28 Chapter 22

29 Chapter 23

30 Chapter 24

31 Chapter 25

32 Epilogue

33 Also by Casey Watson

34 Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

35 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivvvii123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279281

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the army of passionate foster carers out there, each doing their bit to ensure that our children are kept as safe as possible in such a changing and often scary world. As technology is reinvented and becomes ever more complicated for those of us who were not brought up amid such advances, we can only try to keep up, in the hope that we continue to learn alongside our young people.

Acknowledgements

I remain endlessly grateful to my team at HarperCollins for their continuing support, and I’m especially excited to see the return of my editor, the very lovely Vicky Eribo, and look forward to sharing my new stories with her. As always, nothing would be possible without my wonderful agent, Andrew Lownie, the very best agent in the world in my opinion, and my grateful thanks also to the lovely Lynne, my friend and mentor forever.

Chapter 1

Aqua aerobics in February. In February. Had I completely lost my marbles? I couldn’t remember which of my so-called friends had suggested it, but by now I was sorely regretting having agreed to it. Not only was it absolutely Baltic outside, but I had just suffered the most embarrassing incident ever, and as we huddled in our respective changing cubicles in the leisure centre (which were only marginally less Baltic) the same so-called friends – not to mention my sister Donna – were still teasing me about it relentlessly.

‘Oh, Casey,’ Donna said, laughing, ‘such a priceless Barbara Windsor moment!’

‘I must, I must, improve my bust!’ my friend Kate added, gleefully.

And all I could do was take the teasing, and grin and bear it. Or should that have been ‘bare’ it? Definitely. It was such a basic error, after all.

Having not gone swimming in any form for a good couple of years now, I no longer had a suitable swimsuit, and given that this wasn’t the time of year for ‘summer holiday essentials’, the stores didn’t have a great deal of choice. Luckily I had spotted a sale rail and found a front-fastening, gold (of all colours) bikini. And were that not enough to mark me out as a rookie, during a rather robust arms-out-to-the side-and-do-a-windmill thrust, my all-singing, all-dancing, shimmering gold bikini had unclasped with a ping, giving me no choice but to do a duck dive, and leaving me scrabbling around under the water, trying to regain both the shreds of my bikini top and my dignity. But not before the whole class, including the instructor, had witnessed it. I was going to have to seriously rethink how I approached this whole ‘me time’ malarkey.

‘Okay, okay,’ I called out from my own changing booth. ‘I’m so happy I’ve brightened up your morning. And I’m so happy that mobile phones aren’t allowed in the frigging pool, either, because I can only imagine the pleasure you’d have all taken in capturing it for all time.’

Amid the ensuing laughter, as if I’d summoned it, my own phone started to ring. Delving into my changing bag – one that would put Mary Poppins to shame, obviously – I found it and saw it was a call from Christine Bolton, my still relatively new fostering link worker.

Had she called to tease me too? If so, news travelled fast. Quickly drying one side of my face, I put the phone to my ear, first explaining where I was, so she’d understand all the cackles, bumps and bangs.

‘I’m surprised to hear from you again so quickly,’ I added, as I parked my damp bottom on a towel slung on the wooden-slatted bench. I’d only spoken to her the day before and I knew there was nothing on the horizon. Though there had been – up until a few days ago, we’d been earmarked for a particularly difficult teenager badly in need of a calm, stable home. But as often happens in fostering, there was a game-changer. Just a day before all concerned were due in court, a grandparent had kindly stepped forward to offer to take the child in and so the case had been dropped. And to the great relief of all concerned. So we were expecting a lull now – hence all the ‘me-time’. Till another long-term placement came up we were only really doing respite, and that mostly for our most recent child, Miller, who was now in a residential school and with a new primary carer, Mavis.

‘I know,’ Christine replied, ‘and I’m so sorry to bother you in the middle of your swimming, but that mini-break you said you and Mike were hoping to jet off on – have you booked anything yet?’

I immediately wished we had, because I had a hunch I knew what was coming. A lull in the world of fostering was never guaranteed to be anything more than twenty-four hours, and more often than not it wasn’t. I suspected this was the situation here – that an urgent case had presented itself. I wasn’t wrong.

‘No, not as yet,’ I said. ‘Shouldn’t I?’

‘Possibly not. At least, if you’re up for taking a child on. D’you know Kelly and Steve Blackwell? Live out in the sticks and have two small children?’

‘Indeed I do,’ I said. ‘And pretty well. I was Kelly’s mentor for a year.’

Mentoring had always been the unofficial practice in fostering, but over the last couple of years it had become an even more important part of the process. One in which longer-term, more experienced carers were expected to take on the role of mentor to new carers just coming into the field. In my case, this meant Kelly, who I’d met up with fairly regularly, to discuss any problems she might be having and exchange ideas on the best strategies to deal with them. We’d also swapped numbers and email addresses so that we could be on hand in an emergency. It was yet another item on our ever-expanding job descriptions, but I didn’t mind. It built relationships, and up to now it had worked well.

‘Ah yes, of course you were,’ Christine went on. ‘I remember seeing it on your file, now I come to think about it. Even better then. Because it’ll give you some context. The problem is the young lad they have in at the moment. The top and bottom of it is that they can no longer hold on to him, and we were wondering if you might be able to help out. Either for the short term until we find another long-term carer, obviously, or longer term, if that’s something you’d want to think about.’

But I was thinking more about calm, capable Kelly. Both she and her husband seemed pretty good carers to me. ‘Kelly can’t take care of him?’ I asked, surprised. She wasn’t usually fazed by much. ‘Why? And how old is he? What’s his story?’

Christine laughed. ‘You remember telling me about how your son can ask twenty questions in the same sentence? Well, now I know where he gets it from, don’t I? Okay, well first of all you should know that had we not been thinking about you for that teenager that didn’t materialise, we would have asked you to take on this one in the first place. He’s a little lad called Sam Gough – he’s nine, and has an unofficial diagnosis of autism. He was only removed from his mother just over a week ago – a single mum, mental health issues – along with his two siblings, who –’

‘Just over a week ago? So Kelly’s only had them for a matter of days?’

‘Not them. Only Sam. His siblings have been fostered separately.’

This was highly unusual. ‘Because?’

‘Because they’re very frightened of him, apparently. And yes, just the week. He has a number of issues. It could just be the shock of being taken from his family. Could be something completely different. But either way, he’s been bullying Kelly and Steve’s young children, and it’s really impacting on the family.’

So, bad. Bad enough to be separated from his siblings, and bad enough that Kelly wanted him removed after only a week. Which was pretty bad. Pretty challenging. I eyed my sopping bikini. Reflected that aqua aerobics really wasn’t for me. Not least because I already knew what my answer would be. However, protocol dictated that I think about it, and discuss it with my husband before agreeing, so I said what was expected of me and added, as an afterthought, ‘as well as speaking to Mike, I’ll finish dressing and nip into the canteen to give Kelly a quick call. It’s always worth getting things from the horse’s mouth, isn’t it? Plus she’ll be able to enlighten me on the day-to-day business of taking care of him.’

‘Good idea,’ Christine said. And I could tell by her jaunty tone that she knew she’d get her ‘yes’. ‘Oh, and one other thing,’ she said. ‘I know this will probably make you roll your eyes, but from the little I’ve heard about him, he does seem a perfect candidate for the type of programme you used to run – the behaviour modification thing that everyone was raving about a couple of years ago? Anyway, just a thought.’

A thought, or an extra inducement to be sure I didn’t change my mind? If that was the case, then perhaps this little lad was even more challenging than I suspected. Because it was no secret that Christine, having hailed from Liverpool, where our particular programme hadn’t been rolled out, had made it clear at the start of our working relationship that what she thought about the programme I thought so much of was that it was yet another new-fangled bit of nonsense that wouldn’t bear fruit.

And she hadn’t been the only one. In fact, the funding had been pulled after only four years. This was mostly due to tightening of government purse strings, but also – in my humble view – due to a lack of commitment to a philosophy the benefits of which might take a number of years to assess. So while it was true that fostering services were no longer training new carers in how to deliver the programme (and, as a consequence, children were no longer being hand-picked to receive it), those of us who had seen first-hand how effective it had been still used the model, and the principles, whenever we were fortunate enough to foster a child who looked like they might benefit. And here was Christine, the unbeliever, suggesting that Sam might be one such. She obviously needed to find a place for him, and fast.

Half an hour later, finally presentable, and having waved off my still-chuckling tormentors, I was sitting in a booth in the leisure-centre coffee shop, latte in one hand and mobile phone in the other, the not-so-sweet tang of chlorine still clinging to my hair.

‘Oh, Casey, I feel soooo bad,’ Kelly said, after I’d explained what the call was about. ‘I had no idea it would be you they’d ring. You must think I’m such a wuss!’

‘Don’t be silly,’ I reassured her. ‘Honestly, we’ve all been through it. Sometimes you get a child in who just doesn’t work in your particular environment. It happens. It’s obviously not meant to be, so don’t feel bad. I’m just ringing so that you can paint a clearer picture about what’s been going on.’

‘Just about everything,’ Kelly said, before reeling off all of the problems she and Steve had faced in the last week. ‘He’s just such a live wire. I’ve never seen anything like it!’

Which seemed fair enough, because Kelly hadn’t been fostering for very long. If she stuck at it – and I hoped she would – she would doubtless see worse. But it did sound pretty grim; in fact, to call Sam a ‘live wire’ seemed too benign a term, because as well as rampaging around her house, breaking and smashing things indiscriminately, he would apparently hurt her own children at every opportunity.

‘Which I completely understand is all part of him expressing his rage,’ Kelly said. ‘But I can’t take my eyes off him for a minute. And if I try to reason with him, or chastise him, he turns his anger on me instead. I know he’s only small, but it’s like being attacked by a whirling dervish. He really has no self-control, or self-soothing mechanism, at all. Well, perhaps one,’ she added. ‘This peculiar habit of barking and howling, which he does for prolonged periods at a time. And at any time he’s confronted, he snarls. Really snarls. Poor Harvey said yesterday that it was like we had the big bad wolf living in the house.’

Harvey was Kelly’s oldest. Around seven, as I remembered. And I wondered how it must feel to return home from school every day thinking there was a wolf living in your house. I wondered too how they’d come to ask Kelly, who was relatively inexperienced, to take on such a boy, knowing there were two younger children in the house. Not to mention that they already knew his own siblings were so afraid of him that it had been agreed to have them fostered somewhere else.

But that was a question for another day. And I probably already knew the answer: because there wasn’t anyone else. Which Kelly must know too, so I imagined she’d feel pretty bad about passing the buck.

‘So, how does the autism affect him?’ I asked her instead. I’d looked after quite a few children who were on the spectrum and, in my experience, one size certainly didn’t fit all. Each one of mine – and that included my own son, Kieron, who had Asperger’s – had been very different, with different challenges to face.

‘To be honest,’ Kelly admitted, ‘I haven’t even really had the chance to notice. Everything else is so full-on, I just … Oh, Jesus, hang on. Sam! Stop that right now!’

I waited on the line, listening to a symphony of different sounds – shouting and swearing and, at one point, high-pitched screaming. The jolly hold music of a call centre it definitely was not. No wonder her nerves were torn to shreds. Plus, it was Saturday now, of course, so both her kids would be home. And perhaps this had been the straw that had broken the camel’s back.

‘I’m so sorry, Casey,’ she said as she came back to the phone, ‘Sam’s just bitten Harvey and now he’s attacking Sienna. I honestly do not know what to do with him. It wouldn’t be so bad if Steve was home but he’s had to go into work this morning. And I’d take them out, but I – Sam! Right now! I mean it! – God, Casey. I am tearing my hair out here.’

I could tell she was, too, because she sounded on the verge of tears. ‘Look, I can see it’s a bad time,’ I said. ‘You obviously need to step in and get your own two to a place of safety. Shall I give you a call back later, perhaps when the kids are in bed?’

‘Call me?’ Kelly asked, her voice now even more desperate. ‘I was rather hoping you’d come round and take him off me. As in today. Seriously. I know it’s not the best endorsement you ever heard, but I can’t take any more of this. I really can’t.’

Knowing Kelly as I did, I knew she was telling me the truth. She was at breaking point, overwrought, and couldn’t see a way out. It tended to be hard to with all your senses on high alert. No, it didn’t sound so much, just having to oversee a naughty nine-year-old, but I knew there was ‘naughty’ and there was ‘downright demolition-mode’; if she was dealing with the latter in isolation it would be a hard enough job – just in terms of trying to keep the child safe from himself. But with two little ones in the mix – her own little ones – it could be a Herculean task. And there was a world of difference between the odd flaring of temper and what sounded like twenty-four seven all-out warfare.

I knew the drill. I really shouldn’t be making any promises. I should tell Kelly I’d speak to Mike and Christine and get back to her. But how could I? Besides, I was getting fired up now. No, I wouldn’t be diving into any phone boxes, doing a spin and donning tights. But unlike my bikini top, I knew I had the strength for a challenge. And this lad sounded as if he was the word ‘challenge’ personified.

Plus, truth be told, I still had a few demons of my own to exorcise.

‘Don’t worry, love,’ I told Kelly. ‘I’ll take him.’

Chapter 2

No matter how diverse the types of children who’d come to us over the years, my modus operandi for welcoming them rarely differed. In the here and now, one thing took priority over all others; to provide them with their own space – a place of comfort, calm and safety.

It had been a long time since we’d opened our home up to our first foster child, Justin, and as I went through my usual mental checklist for getting Sam’s bedroom ready for his arrival, I reflected on just how much our singular job had become an everyday part of our lives. So much so that, these days, I was ready for every eventuality; stocked to the proverbial gunwales with everything I knew I’d need, or a frightened, disorientated child might want. Which meant that today it was a far cry from those anxious days before Justin was due to move in, when I’d run around like a mad thing, decorating, choosing, shopping and fussing over every detail, every imagined speck of dust.

Today, of course, I didn’t have the luxury of time, but it didn’t matter. It was really just a case of making up Sam’s bed, and making everything nice for him. And as he’d bowled in from football training just an hour or so earlier, I also had Tyler, our long-term foster son, on hand.

Though we never thought of him as that, obviously, because ‘son’ pretty much covered it. He’d been with us seven years now. He was part of us for ever.

‘Mum! Where d’you want this stuff?’ he yelled from halfway down the loft ladder. From where I was smoothing the bedclothes all I could see were his legs and feet.

‘In the conservatory!’ I yelled back.

‘What? Really?’

‘Honestly, love, where do you think I’m going to want it?’

‘Very funny. Not,’ he said, staggering in carrying a giant beanbag, which he dumped, along with the brace of cushions I’d ask him to fetch down for me, right on top of the bed I’d just made up.

‘Not on there,’ I snapped. ‘Now there’ll be wrinkles in the duvet.’

‘God, Mum,’ he huffed. ‘He’s a nine-year-old, isn’t he? You really think he’s going to care if his duvet’s a bit crumpled?’

‘That’s not the point,’ I pointed out. ‘It’s a question of standards. Besides, I’ll care. Anyway, thanks, love. Now go on down and tell your dad I’m almost finished, and that I’ll be inspecting his dusting when I get there.’

I got the usual mock salute, accompanied by the usual grin and eye-roll, and as I always did when a new kid was about to be ‘on the block’, I thought back to the circumstances that had brought Ty himself to us – as angry and distressed a kid as you could ever wish to meet. A tightly wound ball of sheer fury, in fact, who’d greeted me (our first meeting had been at the police station where they were holding him) as if I’d been especially bussed in to torment him. A pint-sized harpy, sent to further ruin his already ruined day.

His ruined life, as it turned out. Well, or so it had seemed at that point. So to have got from that to this – to this lovely young man, who made us proud every day – still felt like a minor miracle. In fact, a series of miracles which, whenever times were tough, reminded me of that old, clichéd mantra – that unconditional love and firm boundaries could take you a very long way.

It had been less than eight hours since I had even heard the name Sam, and in around as many minutes I would be meeting him for the first time, too. Starting off on another journey into the unknown. And, as was fast becoming a norm now, with another almost completely unknown quantity; other than the concerns about his behaviour and the fact that he was in care, I knew almost nothing about this child. Because no one in social services did either.

I had a final check around. For all I knew, Sam could hate the Roblox-themed duvet cover I’d chosen. The blue curtains might offend him, and the fluffy yellow cushions I’d had Tyler bring down for him might, given he was unofficially diagnosed as autistic, make him cringe to the touch. And the books and games I had selected from my ever-growing storage boxes might be way out of his comprehension zone. I really was going in blind on this one – again! – and could only hope I’d hit one or two right notes. The rest I’d have to deal with as happened.

‘Casey! Coffee ready, love!’ Mike called up. ‘Dusting done. Car pulling up. Come and join the welcoming committee.’

I closed the bedroom door and hurried anxiously downstairs. I always had butterflies in my stomach when about to meet a new child but today it was accompanied by another kind of anxiety. One that had been sparked when I’d called Kelly to tell her we were taking Sam and she had responded with such gratitude that it was almost embarrassing – as if I’d phoned her to tell her she’d won the lottery. She and her husband Steve had always seemed such capable, pragmatic carers, so I’d been surprised to hear so much emotion in her voice.

‘I cannot thank you enough, Casey,’ she’d gushed. ‘I owe you. I owe you big time.’

‘You owe me absolutely nothing,’ I’d pointed out. And was just about to add that I was only doing my job when my internal censor (not always that reliable, to be honest) shut my mouth, because to do so would be to imply that she wasn’t. At least I didn’t doubt she’d have seen it that way.

Instead I burbled on about it being easier, since I didn’t have little ones to think about, but when I rang off the intensity of her emotion still dogged me. Just how much of a challenge was this little boy going to be? Surely a child of nine couldn’t be that much of a handful?

I said as much to Mike as he handed me my coffee and we prepared, as a family, to welcome our little visitor together – something that mattered at any time, obviously, but particularly with a child thought to be on the spectrum because change can be hard for such children. So to meet us as a single smiling unit – a wall of warmth and reassurance – would be helpful in managing his inevitable anxiety. Something now made much worse, of course, by this second, sudden, unexpected move and the confusion that would inevitably accompany it.

‘Well,’ Mike said, ‘like you always say yourself, love, it doesn’t matter where they come from, it only matters where they’re going. You already knowing Kelly and Steve shouldn’t really make a difference. And it sounds to me, given the situation with his own siblings, that it might not have been the best choice of family set-up.’ He raised a palm. ‘Though, yes, of course I know there probably wasn’t a choice.’

‘What will be, will be, I suppose,’ I said, automatically checking that the kettle was filled enough to make Christine a cup of tea when she arrived. It was scalding. Mike had obviously beaten me to it, bless him.

And it was only to be Christine, which was highly unusual. A child would usually arrive with their social worker, too. But it turned out that Sam didn’t even have a social worker. It had all happened so fast that the emergency duty team (EDT) had taken care of things, and apparently the only member of staff with space on his books – a Colin Sampson – was away on annual leave till the end of next week.

Colin would be assigned to Sam once he was back, at which point we’d all meet, but, in the meantime, if I had any sort of crisis I would have to call on the duty team. I mentally crossed my fingers that that wouldn’t come to pass. Now I’d agreed to take him on, doing my best ‘knightess on white charger’ impression, I would look pretty stupid if I was calling out the cavalry within the week.

More to the point, the poor lad must be traumatised enough.

‘Mum, I see him,’ Tyler said from his station by the window. ‘Aw, he’s dead tiny, he looks really cute. Not sure what he’s up to, exactly – he seems to be marching on the spot – but he definitely doesn’t look dangerous.’

I’d given Tyler the facts, of course. It was important that he knew what we were dealing with. And following the problems our last foster child, Miller, had caused him, I couldn’t blame him for checking Sam out. Things were okay now; on Miller’s respite visits they rubbed along just fine. But every new child was a journey into the unknown for Tyler too.

And he was right. At first sight, Sam did indeed look very cute. Almost angelic, in fact, with shoulder-length, dirty-blond hair, which hung straight down over his skinny shoulders. And, as Tyler had observed, he seemed to be marching on the spot, while Christine stood by, patiently watching, holding a small suitcase. We all watched him too, till they finally set off down our front path, and I went to the front door to let them in.

Sam was shiny as a pin – Kelly had obviously bought a selection of new clothes for him – and like many a child before him, standing on this very spot, looked every bit as anxious as I’d expected.

‘One hundred,’ he announced, talking to a spot just above his feet. ‘A one-hundred-step path. One hundred steps exactly.’ He then wiped his brow theatrically, and exhaled as if he’d just climbed a very big hill. He straightened the backpack on his shoulders, and tugged on Christine’s coat sleeve. ‘That’s a very long path, Mrs Bolton.’

Though I wasn’t sure what to make of this, that was par for the course. But Christine gave me a quick glance before smiling at him and nodding. ‘It certainly is, Sam, especially when we’ve had to do eighty-five of them on the spot. Sam has a bit of an obsession with the number one hundred, Casey,’ she explained. ‘It couldn’t have been the number five or six, could it, Sam?’

I saw the trace of a smile cross the boy’s elfin features. They’d obviously discussed this. And no doubt Christine would enlighten me later. In the meantime, it had broken the ice, and I laughed as I led them through to the dining area.

Mike was already setting down the teapot, Tyler pouring milk into a mug.

‘Alright, mate?’ he asked Sam. ‘I’m Tyler. Pleased to meet you. Want a drink and a biscuit?’

Sam’s gaze darted towards him, then away again. He shook his head.

‘He’s literally just had his tea,’ Christine explained.

‘Well, in that case,’ Ty continued, as per our usual plan, ‘do you want to come upstairs with me and see your bedroom?’

He held out a hand, and Sam eyed this too. Then, after checking wordlessly with Christine, who nodded an affirmative, began to shrug his backpack from his shoulders.

‘Could you look after my bag, please?’ he asked her politely. ‘It’s a Spider-Man backpack and it’s very, very precious, so you won’t let anyone near it, will you?’

‘Absolutely not,’ Christine assured him. ‘Though why don’t you take it with you? Find a safe place to put it in your new room?’

Darmowy fragment się skończył.