Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Revenant»

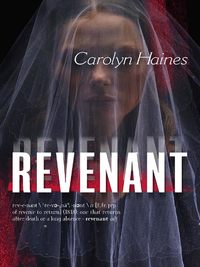

Carolyn Haines

REVENANT

For Alice Jackson—

We had some fun when the Mississippi

Gulf Coast was a reporter’s dream.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I can never write about newspapers and journalists without thanking my parents, who drew me into the profession they loved. When I was so small I had to stand on a wooden box, I disassembled the slugs of hot type to be melted and reset for the next edition of the paper.

My parents, Roy and Hilda Haines, burned with the passion of true journalists, and they passed that love to me.

In my life I’ve been privileged to know many fine reporters and editors. The Sellers family in Lucedale gave me my first paid job at a weekly at the age of seventeen. Leonard Lowry, Fitz McCoy, Elliot Chase, Sarah Gillespie, Robert Miller, Fallon Trotter, John Fay, Buddy Smith, Rhee Odom, Tom Roper, Gary Smith, Ann Hebert, Jim Young, Doug Sease, Bill Minor, Elaine Povich, Ronni Patriquin Clark, Jim Tuten, Lee Roop, B. J. Richey, Phil Smith—each one of them helped me down the road toward becoming a better reporter and also helped me recognize my limitations.

Newspapering gave me opportunities that few young people ever see. I owe the people I worked with many thanks.

As always, I owe thanks to my critique group, the Deep South Writers Salon: Renee Paul, Alice Jackson, Susan Tanner, Stephanie Chisholm, Gary and Shannon Walker and Aleta Boudreaux.

My agent, Marian Young, is the best. And the editorial staff at MIRA can’t be beat. Thank you, Lara Hyde, Valerie Gray and Sasha Bogin.

I’m knocked over by the terrific cover and the hard work that Erin Craig put into creating a design that conveyed so much of the story. This book has been a terrific experience from beginning to end.

Thank you all.

1

A seagull swooped low over the white, man-made beach of Biloxi. The midmorning sun was bright, and I squinted against the glare of the sparkling Mississippi Sound. The water held potential. An accidental drowning wouldn’t be a bad way to go, and it would be so much easier on my parents than suicide. My BlackBerry buzzed against my waist, disrupting the constant whisper of the water, the promises of numbness and sleep. I turned back to my truck and checked the number. The newspaper. I was late again.

A discarded coin cup clattered across the parking lot. Casinos, the new Mississippi cash crop. The Gulf Coast was second only to Las Vegas for gaming, a point of pride for those who saw growth as the only indication of progress. The garish casinos, complete with parking garages and hotels, were a blight, built by people who’d forgotten a storm called Camille and the damage of two-hundred-mile-per-hour winds. Talk about a gamble—putting huge floating barges in the Mississippi Sound. It was 2005, and thirty-six years had passed since Hurricane Camille wiped out the Gulf Coast. But Mother Nature, like a guilty conscience, only feigns sleep.

Of course, mine was the minority opinion in a town that had finally seen the promise of two cars in every garage fulfilled by the economic boost brought by the lure of the one-armed bandits.

It was only March, but already the hurricane experts were predicting a bad year for 2005. In a different place and time, I might have wanted to see the list of construction materials used on the hotels and new condominiums that crowded the coastline. If the construction was not up to standards, a Category Five hurricane, like Camille, could be death and destruction. In the past, that would have caught my professional interest, but not anymore. I was done with all of that.

I drove to the newsroom of the Morning Sun, ignoring the hostile glances of my coworkers as I went into my office and closed the door. They’d converted a conference room to make my office and indentations from the heavy table were still in the carpet. My desk and computer were at the end of the room beside the long narrow window that reminded me of a fortress. If the Injuns, or the liberals, surrounded us, I’d have a place for my shotgun. The paper’s policy would be to shoot on sight.

My telephone rang. “Where the hell have you been? It’s almost ten o’clock. We’re running a daily newspaper here, Carson, not a magazine.”

In my three weeks of employment, nothing had happened that warranted my presence at the paper at eight. “Sorry, Brandon,” I said. “I was busy contemplating suicide, but I’m too much of a coward to carry through with it. So, what’s going on?” I fumbled through a desk drawer for an aspirin bottle. Perhaps I should have apologized to Brandon Prescott, the publisher, but I didn’t care for him or my job.

“Drop the pity party, Carson. We don’t have time for it. They’re bulldozing the Gold Rush. When they started scraping up the parking lot they found a grave with five bodies in it. It’s the biggest story of the decade. Joey’s already there. I want you over there right now. And what the hell good is that pager unless you turn it on!”

Brandon was steamed, but there was always something that had his blood pressure at the boiling point. Lately, it was me, his prize. He’d dragged me out of the gutter and put me in a suit and an office with an official press badge. If I were a better person, I’d be grateful.

“I’m on the way,” I said, surprised at the tingle at the base of my skull. My reptilian brain felt a surge. Five bodies buried at one of the most glamorous—and notorious—nightclubs along the Gulf Coast. It could be a big story. In the ’70s and ’80s, the Gold Rush had been the pre-casino gathering place of the Dixie Mafia and the late-night party place where the young and beautiful of all social strata came to be seen. It was even possible someone had pushed up the tarmac and uncovered Jimmy Hoffa. After all, it was the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Anything was not only possible, but it was also probable.

I walked out of my office and was met with the baleful glares of six reporters. They already knew about the bodies, and they’d been hoping it would be their story. By rights, it should have belonged to one of them. But I had the big name and I got the choicest scraps Brandon tossed. I walked out into the March sunshine, hoping the bodies were either very old or very fresh.

Once upon a time, driving along the Mississippi Gulf Coast had been a pleasure. Miles of lazy, four-lane Highway 90 hugged the beaches where there were more migratory birds than fat sunbathers. With the advent of gambling in 1992, all of that changed. Sunbathers were already on the beach, even though the March sun had barely warmed the water above sixty degrees. For at least a mile ahead the traffic was almost at a standstill. If I didn’t get to the Gold Rush soon, the bodies would be bagged and moved. In an effort to calm down, I turned my radio to a country oldies station. There was always a chance I’d catch a Rosanne Cash tune.

Instead, I got Garth Brooks and “The Dance.” There had been a time when I agreed with the sentiment expressed in the song. I’d changed. There were very few experiences worth the pain. I flipped off the radio and took a deep breath. Traffic started moving, and in another fifteen minutes I was at the club.

Police cars and coroner vans lined the sandy shoulder of the highway, lights no longer flashing. Clusters of men in uniform stood whispering. Biloxi Police Department Deputy Chief Jimmy Riley sat behind the tinted windows of an unmarked car. It would have to be a big case for Riley to put in an appearance.

Mitch Rayburn, the district attorney, was also on the scene, and I’d made it a point to know as much as possible about him. Mitch was smart and ambitious, a man dedicated to protecting his community. There’d been tragedy in his past, but I didn’t know the exact details. Yet. What I saw was a man sincere about distributing justice. So far, he seemed to play a straight hand, which would be a definite detriment to his future political ambitions.

Detective Avery Boudreaux did everything but stomp his foot when he saw me pull up. Avery disliked reporters in general and me in particular. We’d already had a run-in over a stabbing at a local high school.

“Hi, Avery,” I said, because I knew he’d rather swallow nails than talk to me. “I’ll bet the bulldozer operator was shocked.” I started toward the edge of the shallow grave and heard Avery bark an order to stop.

“Let her go,” Mitch said. “We’re going to need the newspaper’s cooperation.”

I almost turned around in shock; Mitch was being amazingly cooperative. Then I figured the crime scene had already been molested by a bulldozer. I could hardly do more damage. The area was at the far back corner of the lot. Stumps and the damaged stalks of vegetation indicated that it had once been a shady, secluded spot.

I looked down into the grave. It was my lucky day. There was no flesh left, only smooth, white bones. Delicate in the bright sun. Five skeletons, five rib cages, five spinal columns embedded in dirt. All of the skulls were intact, the pelvises riding over femurs and tibias. They’d been laid side by side with some gentleness, it seemed. The connective tissue in the joints had disintegrated, so when the bodies were moved, they would fall to pieces. Whoever had buried the bodies had assumed the asphalt would protect them, and they’d been right, for a good number of years.

I caught Joey’s eye. He was standing about twenty feet back with his digital Nikon dangling from his hand. He nodded. I stepped in front of Avery, effectively blocking him. Joey rushed forward and fired off several shots before two cops grabbed him.

“Damn it, Mitch.” Avery thrust me to the side. “I told you we couldn’t trust her!”

“It’s better to let the public know,” I said. “Speculation is far worse than knowledge.”

“Except for the families of the victims.” Avery’s mouth was a thin line. “I should arrest both of you.”

I didn’t let his words register. Brandon Prescott ran a newspaper that thirsted for sensationalism. I knew my job, and even when I didn’t like it, I knew how to do it. There was very little of my old life that I’d held on to, but I was a damn good journalist. I got the story.

“Any idea who the bodies might be?” I directed my question to Mitch. He waved at the cops to release Joey. The photographer dashed for his car to get back to the office.

“Not yet,” Mitch answered.

“Wouldn’t you know, they were just so inconsiderate. They didn’t carry any identification into the grave with them. Can you believe it?” Avery glared at me.

“That’s a great quote, Avery,” I said. “Very professional.”

“That’s enough, both of you.” Mitch’s mouth was a tight line. “There are five dead people here. Let’s focus on what’s important. Avery, we need to cooperate with Carson. We’re not going to be able to keep the media out of this.” He pointed to the highway where a television news truck had stopped. “That’s our real problem.”

“Do you have any idea who the victims are?” I asked Avery again, this time in a more civil tone.

“As soon as we get the medical examiner to give us a time frame for the deaths, we’ll start going through missing-person reports.” Avery was watching the television news crew as he talked.

“When we know something, we’ll call you, Carson,” Mitch promised. “I’d personally appreciate it if you didn’t run the photo of the remains.”

He’d effectively ripped my sails. The photo was needlessly graphic, and he knew I knew it. I hadn’t been in Biloxi long, but Mitch had grown up here. He knew the score. “Talk to Brandon,” I said. “You know I don’t have a say in what gets printed and what doesn’t. Have something good to offer in exchange.”

“We wouldn’t have to negotiate with Prescott if you hadn’t set it up for the photographer.” Avery shook his head in disgust.

“Who owns the Gold Rush now?” I watched the television reporter being held at the edge of the parking lot. My time was running out.

“Alvin Orley sold it to Harrah’s about five years ago,” Mitch said. “It’s been empty for about that long. I think the casino corporation is going to build a parking garage here.”

“Lovely. More concrete.” I looked around at the oak trees that lined the property. With the bulldozers already at work, they were history. “Never let a two-hundred-year-old oak stand in the way of more parking space.”

“Why in the hell did you come back here if Miami was such a paradise?” Avery asked.

I looked him dead in the eye. “I guess when my daughter burned to death and I fell into a haze of alcoholic guilt, wrecked my marriage and got fired, I thought maybe I should leave the scene of my crimes and come home to Mississippi. Biloxi was the only paper that would hire me.” Avery didn’t flinch, but he had the decency to drop his gaze to the ground.

“Alvin’s still doing time in Angola prison,” Mitch said, breaking the strained silence. “I want to personally ask him some questions. I’m going to talk to him this afternoon. You could ride with me, Carson.”

I felt the sting of tears. It had taken me more than two years after Annabelle’s death to be able to control my crying. Now I was about to lose it again because a D.A. stepped out of his professional skin and offered me a ride to a Louisiana prison. I was truly pathetic.

“Thanks. I’ll let you know.” I turned away and walked back to the shallow grave. The five skeletons were lying side by side, heads and feet in a row. I had no idea what had killed them, whether they were male or female, how old they were or why they’d been killed. For all of the things I didn’t know, I was relatively certain that they’d been murdered. The skeletons were perfect. Lying under the asphalt, they’d been safe from predators and animals that normally disturb skeletal remains. I knelt down beside the grave for a closer look.

Avery was watching me, alert to my possible theft of a femur or maybe a scapula. I examined the bones, stopping on the left hand of the first victim. I couldn’t be certain, but it seemed that a finger was missing. I looked at the next body and saw the same thing. Then again on the third, fourth and fifth.

“Hey, Avery,” I called. “The ring fingers are missing on all of them.”

He came to stand beside me, his black eyes assessing me, and not kindly. “We know,” he said. “And that’s something we’d like to keep out of the paper.”

I couldn’t keep a photograph from Brandon, but I could keep this information. At least for a day. “Okay,” I agreed, “until tomorrow. After that, I can’t promise.”

“The M.E. said the fingers were probably severed,” Avery said. “It might be our best clue for catching whoever did this.”

I nodded, still glancing at the bones. Something else caught my eye. Beside each skull were the remains of some kind of material, and beneath that, plastic hair combs. “Look at that,” I said. “Nobody wears hair combs like that anymore. What are the odds that all five bodies would have had combs?”

“These bodies have probably been here at least twenty years. I’ve got somebody checking records to see if we can find out when this parking lot was last paved.”

“You figure they’re all women?” I asked, feeling yet again the tingle at the base of my skull.

“If you jump to a conclusion, Ms. Lynch, please don’t put it in print. There are fools out there who believe what they read in the newspaper.”

“Thanks, Avery.” I was almost relieved to have him back to his normal snarly self.

“I’ll stop by and talk to Brandon,” Mitch said. “And you can decide if you want to ride to Angola with me. We could get there by three, back by seven or so.”

“Thanks. I’ll think about it.” When I glanced toward my truck, I saw that Riley had returned to his desk job. The forensics team had done its work and was bagging the bodies. I’d seen hundreds of the black, zippered bags, but they still left me feeling empty. Would the families of the victims find peace or more horror? I got in my truck and eased into the moving traffic jam that was the highway.

2

Instead of going to the paper, I detoured to city hall. Biloxi was an old sea town. Fishing was once the heart and soul of the settlement, and the preponderance of business development was right along the water on Highway 90 or on Pass Road, which paralleled the coast through two counties. The population was French, Spanish, Yugoslavian, German, Italian and Scotch-Irish with a smattering of Lebanese. The Vietnamese were the newcomers who had earned an uneasy place in the fishing industry. The population was predominantly Catholic, a fact that figured into how the gravy train of state funding was distributed for many years. With the power base situated in the Protestant delta, the Gulf Coast sucked hind tit. The casinos changed all of that. The coast now had the upper hand. King Cotton and the rich planter society of the delta were passé.

Highway 90 still had remnants of the gracious old coast I remembered. Live oaks sheltered white houses with gingerbread trim and green shutters. There was an air of serenity and welcome, of permanence. I drove through one such residential area and then turned onto Lemuse where city hall was located.

When I asked for the records of building permits issued in the 1980s, I discovered that Detective Boudreaux’s minion was one step ahead of me. A police officer had just copied those documents. They were right at hand, and I read with interest that a small addition had been built onto the Gold Rush in October 1981. The parking lot had also been expanded and paved. The five victims had to have been murdered prior to that. I had a place to begin looking and I sped back to the paper.

The newsroom had fallen into the noon slump. Only Jack Evans, a senior reporter, and Hank Richey, the city editor, were still at their desks, and I hoped they wouldn’t see me. They were journalists of the old school, and like me, they’d found themselves employed in an entertainment medium. I slunk past the newsroom to my office and was almost there when I heard Jack yell.

“What’s wrong, Carson? Vomit on your shirt?”

I couldn’t help but smile. Jack was awful, and I liked him for it.

“I just need a little nip from that bottle I keep in my desk.” It wasn’t a joke.

“How bad was it?”

I shook my head. “More strange than gruesome.”

“Mitch is talking to Brandon right this red-hot minute. I hear Joey got some good shots of the skeletons.” Jack grinned. “Mitch will have to trade his soul to keep Brandon from printing that.”

“I warned him.” I sat down on the edge of Jack’s desk. He was a medium-built guy with a head of white hair and a face that tattled all of his vices. In Miami I’d worked with a top-notch reporter who reminded me of Jack. We’d once rented a helicopter to cover some riots. It had been both harrowing and exhilarating.

“So, what did you see?” Jack asked, patting his empty shirt pocket where his Camels had once resided.

When I’d first started as a journalist, this was a game that had honed my eye. “Five skeletons, all uniform in size, buried side by side. I’d say they died around the same time because of the dirt and the decomposition, and also because the parking lot was paved in 1981.” I frowned, thinking. “There were hair combs beside each skull, which would indicate female gender.” I looked at Jack and decided to risk trusting him. “Not for Brandon to know, but their ring fingers were missing.”

“A trophy taker,” Jack said, leaning forward. “This is going to be a big story, Carson. If you play it right, you could climb back up on your career and ride out of this shit hole.” He shook his head, anticipating my question. “I’m too old. Nobody wants a sixty-year-old reporter. But you could do it.”

I felt the numbness start in my chest. My precious career. I stood up. “If I wanted a real career, I wouldn’t be in this dump.” I realized how cruel it was only after I’d walked away. Well, cruelty was my major talent these days.

I grabbed a notebook off my desk and headed to the newspaper morgue, a type of library where newspaper stories were clipped and filed. The murders had to occur before October 1981, so I started there with the intention of working backward through time. October 31, 1981. The front-page photo was of children dressed in Halloween costumes. It was still safe to trick-or-treat then.

Mingled with the newspaper headlines were my own personal memories. I’d been a junior at Leakesville High School that year. I’d met Michael Batson, the first boy I’d ever slept with. He had the gentlest touch and genuine kindness for all living creatures. Now he was a vet, married to Polly Stonecypher, a girl I remembered as pert and impertinent.

The microfiche whirled along the spool. It gave me a vague headache, but then again, it could have been the vodka from the night before. I stopped on a story about Alvin Orley, the former owner of the Gold Rush. He was handing over a scholarship check to the president of the local alumni group of the University of Mississippi. I calculated that was right before his involvement in the murder of Biloxi’s mayor. I noted the date on my pad.

Cranking the microfiche, I moved backward through October. It was at the end of September when I noticed the first photos of the hurricane. Deborah. It had been a Category Three with winds up to 130 miles per hour. She’d hit just west of Biloxi, coming up Gulfport Channel. Those with hurricane experience know it wasn’t the eye that got the worst of a storm, but the eastern edge of the eye wall. Biloxi had suffered. There were photos of boats in trees, houses collapsed, cars washed onto front porches. It had been a severe storm, but not a killer like Camille. In fact, there were only two reported deaths. I stared again at the story, my eyes feeling unnaturally dry.

The D.A.’s brother, Jeffrey Rayburn, and his new bride, Alana Williams Rayburn, had drowned in a boating accident September 19. The young couple had been headed to the Virgin Islands for a honeymoon when they’d been caught in Hurricane Deborah.

The boat had been found capsized off the barrier islands a week after the storm had passed. Neither body was recovered.

The mug shot of the bride showed a beautiful girl with a radiant smile and blond hair. Dark-haired, serious Jeffrey was the perfect contrast. They were a handsome couple.

In a later edition of the paper I discovered a photo of the funeral, matching steel-gray coffins surrounded by floral arrangements. The slug line Together In Death made me cringe. The newspaper had a long and glorious history of sensationalism. As I studied the photo more closely, I saw a young Mitch Rayburn standing between the coffins. I recognized the grief etched into his face, a man who’d lost everyone he loved. I understood how he’d become a champion for justice as he tried to balance the scales for others who’d suffered loss.

I turned my attention to another short story about the tragic drownings. There was a quote from Mitch, who said that radio contact with the boat had been lost during the storm. As soon as the weather had cleared, search-and-rescue teams went out, but they found only the damaged sailboat.

“The coast guard believes that Jeffrey and Alana were swept overboard and that the boat drifted until it hit some shallows,” Mitch had said. “I appreciate all of the efforts of the coast guard and the volunteers who helped. I can only say that I’d never seen my brother happier than he was the day he set sail with his new bride.”

On more than one occasion, my mother had accused me of being incapable of sympathizing with others, and maybe she was right. I felt little at the deaths of a newly married couple, but for Mitch, the one left behind to survive, I felt compassion. Survivor’s guilt would have ridden him like a poor horseman, gouging with spurs and biting with a whip. I knew what that felt like. I lived with it on an hourly basis. I wondered how Mitch managed to look so rested and drug free.

I pushed back my chair and paced the small room, consumed with a thirst for a drink. At last, I sat down and spooled the microfiche backward. Mid-September gave way to stories about the Labor Day weekend, and then I saw the front-page story in the September 3 edition. No Clues In Disappearance Of Fourth Coast Girl. I scanned the story, which was a simple recounting of all the things the police didn’t have—suspects, theories or physical evidence of what had happened to Sarah Weaver, nineteen, of d’Iberville, a small community on the back of Biloxi Bay, where fishermen had resided for generations. It was a tight community of mostly Catholics with family values and love of a good time. In 1981, the disappearance of a girl from the neighborhood would have been cause for great alarm.

What the police did know was that Sarah was a high school graduate who’d been going to night school at William Carey College on the coast to study nursing. She disappeared on a Friday night, the fourth such disappearance that summer. She’d been employed part-time at a local hamburger joint, a teen hangout along the coast. She was popular in high school and a good student.

There were several paragraphs about the panic along the coast. Fathers were driving their daughters to and from work or social events. The police had talked about a curfew, but it hadn’t been implemented yet. Two Keesler airmen had been picked up and questioned but released. Fear whispered down quiet, tree-lined streets and along country club drives. Even the trailer parks and brick row subdivisions were locking doors and windows. Someone was stalking and stealing the young girls of the Gulf Coast.

I studied Sarah’s picture. She had light eyes—gray or blue—that danced, and her smile was wide and open. Was she one of the bodies in the grave? I couldn’t imagine that such information would be any solace to her family. If they didn’t know she was dead, they could imagine her alive. She would be forty-three now, a woman still in her prime.

In my gut, I felt it was likely that she was the fourth victim. But who was the fifth? There’d been no other girls reported missing, at least not in the newspaper, prior to the paving of the Gold Rush parking lot. I’d go back and read more carefully, just in case I’d missed something.

I took down Sarah Weaver’s address and skipped to the beginning of the summer. It didn’t take me long, scrolling through June, to find Audrey Coxwell, the first girl to go missing, on June 29. This story was played much smaller. Audrey was eighteen and old enough to leave town if she wanted. She was a graduate of Biloxi High and a cheerleader. She was cute—a perky brunette.

Her parents had offered a reward for any information leading to her recovery. I noted their address.

In the days following Audrey’s disappearance, there was little mention of her in the paper. Young women left every day. She was forgotten. No trace had ever been found of her. The reward was never claimed.

On July 7, I found the second missing girl, Charlotte Kyle, twenty-two, the oldest victim so far. The high school photo of Charlotte showed a serious girl with sad eyes. She was one of five siblings, the oldest girl. She was working at JCPenney’s.

This story was on the front page, but it wasn’t yet linked to Audrey’s disappearance. The newspaper or the police hadn’t considered the possibility of a serial killer on the loose. This was 1981, a time far more innocent than the new millennium.

I scanned through the rest of July. It was August before I found Maria Lopez, a sixteen-year-old beauty who looked older than her age. In her yearbook photo she was laughing, white teeth flashing and a hint of mischief in her dark eyes. There was also a picture of her mother, on her knees on the sidewalk, hands clutched to her chest, crying.

My hand trembled as I put it over the photo. I could still remember the feel of the strong hands on my arms, dragging me away from my house. My legs had collapsed, and I’d fallen to my knees inside my front door. A falling timber and a gust of heat had knocked me backward, and the firemen had grabbed me, dragging me back. I’d fought them. I’d cursed and kicked and screamed. And I’d lost.

The door of the newspaper morgue creaked open a little and Jack stood there, a cup of coffee in his hand. “I put a splash of whiskey in it,” he said, walking in and handing it to me. He closed the door behind him. “Everyone knows you drink, Carson, and they also know you haven’t contributed a dime to the coffee kitty. The second offense is the one that will get you into trouble.”

He was kind enough not to comment as my shaking hand took the disposable cup. I sipped, letting the heat of the coffee and the warmth of the bourbon work their magic.

“Carson, if you’re not ready, tell Brandon. He’s invested enough in you that he won’t push you over the edge.”

“I can do this.” Right. I sounded as if I were sitting on an unbalanced washing machine.

“Okay, but remember, you have a choice.”

I started to say something biting about choices, but instead, I nodded my thanks. “Where’d you get the bourbon?”

“You aren’t the only one with a few dirty secrets.” He grinned. “What did you find?”