Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

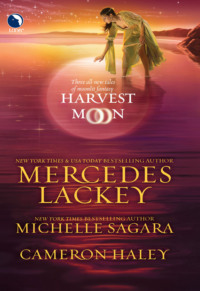

Czytaj książkę: «Harvest Moon: A Tangled Web / Cast in Moonlight / Retribution»

Selected praise for A Tale of the Five Hundred Kingdoms series by New York Times bestselling author

MERCEDES LACKEY

“Wry and scintillating take on the Cinderella story…Lackey’s tale resonates with charm as magical as the fairy-tale realm she portrays.”

—BookPage on The Fairy Godmother

“This Tale of the Five Hundred Kingdoms novel is a delightful fairy-tale revamp. Lackey ensures that familiar stories are turned on their ear with amusing results.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Snow Queen

Selected praise for The Chronicles of Elantra series by New York Times bestselling author

MICHELLE SAGARA

“Intense, fast-paced, intriguing, compelling and hard to put down, Cast in Shadow is unforgettable.”

—In the Library Reviews

“Sagara swirls mystery and magical adventure together with unforgettable characters in the fifth Chronicles of Elantra installment.”

—Publishers Weekly on Cast in Silence

Selected praise for the Underworld Cycle series by

CAMERON HALEY

“Mob Rules is exciting and fresh, with a complex and conflicted heroine who grabs your attention and doesn’t let go. This book will make you fall in love with urban fantasy all over again!”

—Diana Rowland, author of Mark of the Demon

MERCEDES LACKEY

is the acclaimed author of more than fifty novels and many works of short fiction. In her “spare” time she is also a professional lyricist and a licensed wild bird rehabilitator. Mercedes lives in Oklahoma with her husband and frequent collaborator, the artist Larry Dixon, and their flock of parrots.

MICHELLE SAGARA

has written more than twenty novels since 1991. She’s written a quarterly book review column for the venerable Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction for a number of years, as well as dozens of short stories. In 1986 she started working in an SF specialty bookstore, where she continues to work to this day. She loves reading, is allergic to cats (very, which means they crawl all over her), is happily married, has two lovely children and has spent all her life in her native Toronto—none of it on Bay Street.

CAMERON HALEY

Since graduating from Tulane University, Cameron Haley has been a law school dropout, a stock broker, an award-winning game designer and a product manager for a large commercial bank, but through it all has never stopped writing. An active member of Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Cameron is hard at work on the second book in the Underworld Cycle. Cameron lives in Minneapolis. For the latest dirt, visit www.cameronhaley.com.

Harvest Moon

Mercedes Lackey

Michelle Sagara

Cameron Haley

CONTENTS

A TANGLED WEB

MERCEDES LACKEY

A TANGLED WEB

EPILOGUE

CAST IN MOONLIGHT

MICHELLE SAGARA

CAST IN MOONLIGHT

RETRIBUTION

CAMERON HALEY

RETRIBUTION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A TANGLED WEB

MERCEDES LACKEY

A TANGLED WEB

It was the usual perfect day in Demeter’s gardens in the Kingdom of Olympia. Birds, multicolored and with exquisite voices, sang in every tree. Flowers of every sort bloomed and breathed delicate perfumes into a balmy breeze that wandered through the glossy green foliage. It would rain a little after sundown, a gentle, warm rain that would be just enough to nourish, but not enough to interfere with anyone’s plans. The only insects were the beneficial sort. Troublesome creatures were not permitted here. When a goddess makes that sort of decision, you can be sure She Will Be Obeyed.

Now and again a dramatic thunderstorm would roar through the mountains, reminding everyone—everyone not a god, that is—that Nature was not to be trifled with. But it stormed only when Demeter and Hera scheduled it. Everyone had plenty of warning—in fact, some of the nymphs and fauns scheduled dances just for the erotic thrill of it. Zeus enjoyed those days as well, it gave him a chance to lob thunderbolts about; and the other gods on Olympus would be drinking vats of ambrosia and wine and encouraging him.

Meanwhile, on this perfect afternoon of this perfect day, in this most perfect of homes in the center of the most perfect of gardens, Demeter’s only daughter, Persephone, stood barefoot on the cool marble floor of the weaving room and stared at the loom in front of her, fuming with rebellion.

There was nothing in the little weaving room except the warp-weighted loom, and since you had to get the light on it properly to see what you were doing, you had to have your back to the open door and window, thus being deprived of even a glimpse of the outdoors. It was maddening. Persephone could hear the birdsong, smell the flowers, and had to stand there weaving plain dyed linen in the dullest of patterns.

Small as the room was, however, Persephone was not alone in it. There was a tumble of baby hedgehogs asleep in a rush-woven basket, and a young faun sitting on the doorstep, watching her from time to time with his strange goat-eyes. There were doves cooing in a cornice, a tumble of fuzzy red fox-kits playing with a battered pinecone behind her. Anything Persephone muttered to herself would be heard, and in the case of the faun, very probably prattled back to her mother. Demeter would sigh and give her The Look of Maternal Reproach. After all, it was a very small thing she had been tasked with. It wasn’t as if she was being asked to sow a field or harvest grapes. It wasn’t even as if she was weaving every day. Just now and again. Yes, this was all very reasonable. There was no cause for Persephone to be irritated.

Of course there was, but it was a cause she really did not want her mother to know about.

Persephone wanted to scream.

She had the shuttle loaded with thread in one hand, the beater-stick in the other, and stared daggers at the half-finished swath of ochre linen before her. Oh, how she loathed each. Not for itself, but for what it represented.

I love my mother. I really do. I just wish right now she was at the bottom of a well.

Persephone took the beater-stick and whacked upward at the weft she had created. Of all the times for her mother to decide that the weaving of her new cloak had to be done…this was the worst. In fact, the timing could not possibly have been worse. She had spent weeks on this plan, days setting it up, gotten everything carefully in place, managed to find a way to get rid of the nymphs constantly trailing her, and now it was ruined. Stupid Thanatos would probably drive the chariot around and around a few dozen times, forget what he was supposed to do and head back to the Underworld; he was a nice fellow, but not the sharpest knife in the kitchen. Well, really, how smart did you have to be to do the job of the god of death? Just turn up at the right time, escort the soul down to the Underworld, and leave him at the riverbank for Charon. Not something that took a lot of deep thinking.

And poor Hades—oh, wait, Eubeleus, she wasn’t supposed to know it was Hades—would spend half the day questioning him until he finally figured out what had happened. It had to be Thanatos, though, that was the only way this would work. Otherwise, things got horribly complicated.

She wasn’t supposed to know she was going to be carried off to the Underworld, just as she wasn’t supposed to know her darling wasn’t a simple shepherd. She was supposed to be “abducted” by “a friend with a chariot.” But she had known Hades for who he was almost from the beginning, and given that her darling was Hades, who else would drive his chariot? Not Hypnos, that would be incredibly foolhardy. Certainly not Charon. Minos, Rhadamanthus or Aeacus? Not likely. First of all, Persephone had the feeling that the former kings and current judges intimidated Hades quite a bit, and he wasn’t likely to ask them to do him that sort of favor, never mind that he was technically their overlord. And second, she had the feeling that he was afraid if one of them did agree, he might be tempted to keep her for himself. Poor Hades had none of the bluster and bravado of his other “brothers,” Poseidon and Zeus. He second-guessed himself more than anyone she knew. That was probably another reason why she loved him.

Of course, Hades didn’t realize she knew the other reason why the abductor had to be Thanatos, because he didn’t know she knew—well, everything.

We can set it up again, she promised herself. It wasn’t the end of the world. She was clever, and “Eubeleus” was smitten. Even if she hadn’t met all that many men—thanks to Mother—she could see that. His feelings went a lot deeper than the lust the nymphs and fauns and satyrs had for each other too; the way he had been so patient, so careful in his courtship, spoke volumes. He was willing to be patient because he loved her.

And she was smitten in return. She didn’t know why no one seemed to like the Lord of the Underworld. It wasn’t as if he was the one who decided how long your life would be—that could be blamed on the Fates—and he wasn’t the one who carried you off; that was Thanatos. He was kind—it was hard being Lord of the Dead, and if he covered his kindness with a cold face, well, she certainly understood why. No one wanted to die. No one wanted to have everything they’d said and done and ever thought judged. No one wanted to leave the earth where things were lively and interesting when you might end up punished, or wandering the Fields of Asphodel because you were ordinary. And everyone, everyone, blamed Hades for the fact that they would all one day end up down there.

The Underworld was not the most pleasant place to live, unless you were remarkable in some way. From what she understood, on the rare occasions when she’d listened to anyone talking about it, Hades didn’t often get a chance to spend time in the Elysian Fields where things were pleasant—he mostly got stuck watching over the punishment parts. If he was very sober, well, no wonder! He needed a spot of brightness in his life. And she would very much like to be that spot of brightness.

Besides being kind, and patient, and considerate, he never seemed to lose his temper like so many of the other gods did. He was also quite funny, in the dry, witty sense, rather than the hearty practical joking sense like his brother-god Zeus.

She had started out liking him when they first met and he was pretending to be a shepherd. And as she revisited the meadow where he kept up his masquerade many times, she found “liking” turning into something much more substantial rather quickly. They’d done a lot of talking, some dreaming, and a fair amount of kissing and cuddling, and she had decided that she would very much like things to go straight from the “cuddling” to the “wild carrying-on in the long grass” that the nymphs and satyrs were known for. But he had been unbelievably restrained. He wanted her to be sure. Not like Zeus, oh, no! Not like Poseidon, either! They’d been seeing each other for more than a year now, and the more time she spent with him, the more time she wanted to spend with him. Finally he had hesitantly asked if she would be willing to defy her mother and run away with him, and she had told him yes, in no uncertain terms whatsoever.

He never seemed to have even half an eye for anyone else, either. And not many males paid attention to little Persephone—though it was true she didn’t get a chance to see many, the few times she had been up to Mount Olympus with her mother, she might just as well not have been there.

It would have been hard to compete for the attention of the gods anyway. She wasn’t full-bodied like her mother—face it, no one was as full-bodied as her mother except Aphrodite. She didn’t make men’s heads turn when she passed. By all the powers, men’s heads turned when just a whiff of Demeter’s perfume drifted by them! Aphrodite might be the patron of Love, but Demeter was noticed and sought after just as much. Zeus even gave her that sort of Look, when he thought Hera wasn’t watching; Poseidon would always drop leaden hints about “renewing the acquaintance.” Not that she noticed. She was too busy being the mother of everything that wandered by and needed a mother. Demeter, goddess of fertility, was far more of a “mother” than Great Hera was. Hera couldn’t be bothered. Demeter yearned to mother everything.

Oh, yes, everything. As Persephone grew up, she had resigned herself to being part of a household filled to bursting with babies of all species. Fawns and fauns, nests full of birds, wolf-cubs and wild-kits, calves and lambs, froglets and snakelets, mere sprouts of dryads; if a species could produce a baby and the baby was orphaned, Demeter would take it in. Very fine and generous of her, but it meant that even an Olympian villa was filled to the bursting, and Persephone shared her room with whatever part of the menagerie didn’t fit in anywhere else. She might have a great many playmates, but she never had any privacy.

Or, for that matter, silence.

Demeter sailed through it all with Olympian serenity. After all, she was a goddess—granted, a goddess of a tiny Kingdom, one you could probably walk across in three days—but still, she was a goddess, and a goddess was not troubled by such things.

Her daughter, however…

Her daughter would like a place and a space all her very own, thank you, into which nothing could come unless she invites it. Is that so much to ask?

The fox-kits had gone looking for more adventures, but there were still four of the foundlings here in the weaving room, ensuring she didn’t have any privacy. Not counting the hedgehogs, the faun was still in here, now there was a nymph sorting through the yarn to find something to use to weave flower crowns with, and there were a couple of sylphs chatting in the windowsill, for no other reason but that the windowsill was convenient. Unless, of course, Demeter had sent them to keep an eye on her. Persephone threw the shuttle through the weft again, trying not to wince at the noises the little faun by the door was making, trying to master his panpipes for the first time.

If Demeter had her way, Persephone would be the “little daughter” forever. Though nearly twenty, she’d aged so slowly that her mother was used to thinking of her as too young for any separate life. She’d never be alone with a male, never have an identity of her own. There was no doubt that Zeus himself was infatuated with Demeter, though he would never say so to his wife, nor probably even to Demeter herself. After all, Demeter was in charge of marriage vows, so she would take a dim view of that. But that was why it was no use complaining to Zeus. He would just pat her on the head, call her “Little Kore” (Oh, how she hated that childhood nickname!) and tell her that her mother knew best.

And Hera would take Demeter’s side too, as would Hestia. Aphrodite would probably take Persephone’s part, if only for the sake of mischief, but having Aphrodite on your side was almost worse than having her as your enemy. Whatever Aphrodite wanted, Athena would oppose. And any god who wasn’t infatuated with Demeter would still side with her, because she controlled the very fertility of this Kingdom. No god wanted to risk her deciding that nothing would grow in his garden…or that his “plow” would fail to work the “furrow” properly…

Bah!

The loom rocked a little with the vigor of her weaving, the warp-weights knocking against each other as she pulled the heddle rod up and dropped it back again and beat the weft into place with her stick. She hated the loom, she hated standing at it, she hated the monotonous toil of it, and hated that although her mother considered it to be a proper “womanly” task, she was not considered to actually be a woman.

She luxuriated in her grievances for a good long time, until she had actually woven a full handbreadth of cloth. But she could never hold a temper, and once she started losing the anger, what Hades called her “clever” self came to the fore, and she found herself thinking… But on the other hand…

Oh, the curse of being able to see, clearly, both sides of everything! That was why she could never stay angry, no matter what, no matter how aggrieved she felt. And no one knew Demeter better than her own daughter did.

Could she really blame her mother for wanting her to stay a baby forever? Every single baby creature that left this household, Demeter watched go with sorrowful eyes. Sometimes she even wept over them. She hated losing them, hated seeing them go out into the dangerous world, even though their places were immediately taken by yet more foundlings. After all, the dangerous world was why they were foundlings in the first place.

Demeter’s heart was as tender as it was large. It was impossible, when she looked at you with those enormous, loving eyes, not to love her back. Persephone knew, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that her mother loved her. Not as a little image of herself, not as a shadow, and not as a possession. Loved her. And wanted to keep her protected and safe forever.

But…being manipulated by love was still being manipulated. How long would it take before her mother allowed her to grow up and leave, as she did everything else in this household?

Or was she a special case who would never be allowed to grow? Her temper flared as frustration took over from understanding.

Persephone threw the shuttle again, beat at the weft with angry upward strokes, and the warp-weights clacked together.

Demeter glanced in at her daughter at the loom and sighed. There was no doubt that she was angry, probably at being sent to work when what she really wanted to do was be with her playmates, lazing about in the meadow. But the nymphs had tasks of their own to do today, and Demeter was not going to allow her darling to wander about unescorted. She had tried to explain that, but Persephone was hardly in the mood to listen. There were times when Demeter wondered if she would ever grow up.

But more times when she dreaded the day when she did. That would mean losing her, and things would change between them forever. Little Kore would vanish, and someone else would take her place, a stranger that Demeter might not recognize, someone who would have ideas of her own, and no longer have to listen to her mother’s wise words. Demeter absolutely hated the idea that one day she would lose her little girl…if only there was a way to keep her little forever! But there was no doubt, given Kore’s budding body, that even if it were possible to do so, the time to do so was long, long past.

She wished, sometimes, that she had the instincts of a mother animal. Animals knew that there is only room for one adult in the territory—and eventually even the most devoted mother animal drives her own children away. It would be easier to feel her love turning into irritation—easier than the pain of knowing that one day Kore would grow into her given name and no longer depend on her mother for anything.

There were other issues at hand; this was not a good time for Kore to assert her growing womanhood. There simply was no one suitable for her to assert it with. It troubled Demeter deeply that there was no one among the Olympians that she thought was a decent match for her daughter, and a mortal—well, that was just out of the question…the loves of gods and mortals were inevitably tragic. Zeus was out of the question, Poseidon was her father…maybe. There was some confusion over those things. Apollo never even gave her a second glance. Hephaestus never looked past Aphrodite. Hermes? Never! Other, lesser gods? Not one of them was a fit husband for the daughter of Two of the Six. Perhaps a new Olympian will join us, one that is worthy of being her consort. One with real power, but even more important, one that won’t treat her as Zeus treats Hera. One who will be devoted to her and not wander off to the bed of any female that catches his eye. With an effort of will, she reminded herself of what the Olympian gods truly were. Their numbers were added to—albeit slowly—all the time. And even though the tales of the mortals made them all out to be brothers and sisters, or at the least, closely related—that wasn’t actually true.

Which was just as well, considering how Zeus hopped beds. On the other hand, perhaps one day that bed hopping might produce a male that was as unlike his father in that way as possible. Demeter would be willing to welcome the right sort of part-mortal for her girl. Someone faithful, intelligent, and able to think beyond the urges of the moment.

If there was a drawback to being a god, it was that so much power seemed coupled with so little forethought. Forethought…. Prometheus? No, she had to dismiss that, though with regret. The Titan was currently in Zeus’s bad graces, and she wouldn’t subject Persephone to the results of that. Besides, Prometheus, unlike his brother, had never shown much of an interest in women.

Then, again, finding a man in Olympus was never easy.

Demeter reflected back to the early days of her existence. Kore was the result of one of those early indiscretions on the part of Poseidon (although now they said her father was Zeus), though truth to be told, Demeter had quite enjoyed herself once she realized what the sea-patron was proposing. It wasn’t as if she’d had a husband or he a wife in those days.

Things would be different for Kore. There would be no flitting off to some other light of love. Kore would never know the ache in her heart of watching the male she adored losing interest in her. Not if Demeter had anything to say about it.

Perhaps, Demeter reflected, she had sheltered the girl too much. She just seemed so utterly unprepared for life. There was nothing about her that said “woman,” from her short, slender figure, to her mild blue eyes that seemed to hold no deeper thoughts than what color of flower she should pick or what dinner would be. And Demeter despaired of her ever attracting the attention of a man; charitably one could describe her hair as straw-colored, but really, it was just a yellow so pale it looked as if it had faded in the sun, her eyes were not so much light-colored as washed out, and no amount of sun would bring a blush to her cheek. And one had only to walk with her to see how the eyes of men slid over her as if they did not see her. Poor child. It was utterly unfair. Demeter could not for the life of her imagine how two gods as robust as she and Poseidon had managed to produce this slender shaft of nothing.

No, she was not ready for life. Demeter sighed and resigned herself to that fact. Kore needed nurturing and cultivation still. There was no one, god nor mortal, who was more adept at both than Demeter. Perhaps in another year, perhaps in two, she would finally begin to bloom, those pale cheeks would develop roses, and she’d ripen into a proper woman by Demeter’s standards. Then Demeter could educate her in the ways of man and woman, give her all the hard-won wisdom she had garnered over the years, and (yes, reluctantly, but then at least the child would be a woman and would be ready) let her go.

Until then, she was safest here, at her mother’s side.

Brunnhilde stretched in the sun like a cat, all her muscles rippling, and those gorgeous breasts pressing against the thin fabric that left nothing at all to the imagination. Leopold reflected happily that she looked absolutely fantastic without all the armor.

She looked good in it; in fact, she would look good in anything, of course, but Leopold was a man, after all, and he preferred his wife without all the hardware about her. In the gowns of his home, in the more elaborate gowns of Eltaria—the Kingdom where they’d met—in a feed sack, even. He had to admit, though, he liked her best of all in the costume of this country, which seemed to consist of a couple of flaps of thin cloth, a couple of brooches and a bit of cord. Marvelous! Her golden hair spilled in waves down to the ground, actually hiding more than the clothing did; her chiseled features seemed impossibly feminine when framed by the flowing hair. Her blue eyes had softened under the influence of this peaceful place, and her movements had taken on a grace that he hadn’t expected.

Maybe it was being without armor. The armor made you walk stiffly, no matter how comfortable it was. And the gowns of his homeland and of Eltaria seemed to involve some female underpinnings that were almost as formidable as armor.

She had the most wonderful legs he had ever seen, and it was nice to see them without greaves, boots, or skirts getting in the way of the view.

“So what is this place again, and why are we here?” he asked, lazing on his side with his hand propping up his head and a couple bunches of luscious grapes near at hand. Oh, what a woman! One moment, she was right at his side, joyfully hacking away at whatever monster it was they had been summoned to get rid of—the next she was gamboling about in a meadow as if she had never seen a sword. This was the life. It was fantastic to be doing heroic deeds together, but it was equally fantastic to have this moment of absolute indolence too.

Brunnhilde finished her stretching and began combing her hair, which, as there was rather a lot of it, was a time-consuming process. “Olympia. They don’t have a Godmother because they have gods instead.” She frowned. “Which is not altogether a good idea. I mean, look at Vallahalia.”

Leo picked a grape and ate it, still admiring the view. The sweet juice ran down his throat and at this moment, tasted better than wine. “I have to admit I am rather confused about that. If Godmothers are so good at keeping things from getting out of hand, why are gods so bad at it?”

“I’m not sure.” Brunnhilde paused, and put the brush down on her very shapely knee to regard him with a very serious and earnest gaze. “The ravens told me once that gods are nothing more than another kind of Fae, who get power and shape from worship and the mortals who worship them. So I suppose it’s because we are made in mortal image? Formed the way that mortals would choose to be themselves, if they had godlike powers?”

“Hmm, awkward,” Leo acknowledged. “Given that every man I know would think he was in paradise if he could carry on with women the way the gods do. And given that gods don’t seem to suffer the sorts of consequences from that sort of carrying-on the way mortals do.”

“And other things. Mortals, given the choice, would rather not think too far ahead, or even think at all. So—the gods they worship don’t, either.” Brunnhilde nodded, and took up the brush again. “Then, of course, because awful things happen, the logical question becomes Why didn’t they see this coming? and then the mortals make up all sorts of excuses for why infallible gods end up being very fallible indeed. Like Siegfried’s Doom. Then they make us live through it. Ridiculous, really. I wish that there were no such things as gods. I’d rather be a nice half-Fae Godmother, and be on the side of making The Tradition work for us, instead of on us.”

“But if you had been, I would never have met you, and that would be a tragedy.” Leo grinned at her. She twinkled back at him.

“I don’t think Wotan likes the idea of the others knowing about our true nature,” she observed. “He’d rather we all believed the creation stories, which, even before the ravens told me about being Fae, I didn’t entirely believe. My mother, Erda, told me there was no nonsense of me springing forth fully formed from Wotan’s side, or his head, or any other part of him. I was born like any of the others, I was just first.” She sighed. “Poor Mother. The shape and fate The Tradition forced her into was rather…awkward.”

“Your mother is very…practical, and she seems to have done the best she can with her situation,” Leo said, doing his best to restrain a shudder at the thought of that half woman, half hillside, who had done her awkward best to make polite talk with her new son-in-law without lapsing into fortune-telling cries of doom. “I was going to say ‘down-to-earth,’ but that is a bit redundant.”

Brunnhilde barked a laugh. “Since she is the Earth, I would say so. It’s a shame that the northlanders are so wretchedly literal minded.”

Her nephew Siegfried’s escape from his fate had seriously disturbed the northlanders’ unswerving view of The Way Things Were, and had shaken them all up a good deal. Having Brunnhilde take up with a mortal, and an outsider, had shaken them up even more.

That just might be all for the best. If it shakes them up enough to start changing how The Tradition works up there, everyone will be better off.

Once they had left Siegfried and Rosa, Queen of Eltaria and his new bride, Leo and Brunnhilde had worked their way up to the northlands to break the news of their marriage to Brunnhilde’s mother in person—in no small part because they weren’t sure Wotan had done so. It had been an interesting meeting, if a bit unnerving. He’d sensed that Erda hadn’t really known whether to manifest as a full woman and offer mead and cakes, or manifest as a hill and leave them to their own devices. She’d opted for a middle course, which made for a peculiar meeting at the least. He’d ignored the beetle and moss in his mead and brushed the leaves from his cake without a comment, and tried to act like a responsible son-in-law.

“My mother is delusional, as they all are,” Brunnhilde responded dryly. “I’d come to that conclusion once I saw what life was like outside of Vallahalia, long before you woke me up, you ravisher.”