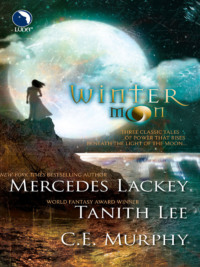

Czytaj książkę: «Winter Moon: Moontide / The Heart of the Moon / Banshee Cries»

Praise for

MERCEDES LACKEY

“She’ll keep you up long past your bedtime.”

—Stephen King

“[A] wry and scintillating take on the Cinderella story…resonates with charm as magical as the fairy-tale realm she portrays.”

—BookPage on The Fairy Godmother

“With [Lackey], the principal joy is story; she sweeps you along and never lets you go.”

—Locus

Praise for

TANITH LEE

“Lee’s prose is a waking dream, filled with tropical sensualities.”

—Booklist

“Tanith Lee is an elegant, ironic stylist—one of our very best authors.”

—Locus

Praise for

C.E. MURPHY

“Murphy delivers interesting worldbuilding and magical systems, believable and sympathetic characters and a compelling story told at breakneck pace.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews on Heart of Stone

“Thoroughly entertaining from start to finish.”

—Award-winning author Charles de Lint onThunderbird Falls

MERCEDES LACKEY

is the New York Times bestselling author of the Heralds of Valdemar and A Tale of the Five Hundred Kingdoms series, plus several other series and stand-alone books. Mercedes has more than fifty books in print, and some of her foreign editions can be found in Russian, Czech, Polish, French, Italian and Japanese. She has collaborated with such luminaries as Marion Zimmer Bradley, Anne McCaffrey and Andre Norton. She lives in Oklahoma with her husband and frequent collaborator, Larry Dixon, and their flock of parrots.

TANITH LEE

was born in 1947, in England. Unable to read until she was almost eight, she began to write at the age of nine. To date she has published almost seventy novels, ten short-story collections and well over two hundred short stories. Lee has also written for BBC Radio and TV. Her work has won several awards, and has been translated into more than twenty languages. She is married to the writer/artist John Kaiine. Readers can find more information about Lee at www.TanithLee.com or www.daughterofthenight.com.

C.E. MURPHY

holds an utterly impractical degree in English and history. At age six, Catie submitted several poems to an elementary school publication. The teacher producing it chose (inevitably) the one Catie thought was the worst of the three, but he also stopped her in the hall one day and said two words that made an indelible impression: “Keep writing.” It was sound advice, and she’s pretty much never looked back. More information about Catie and her writing can be found at www.cemurphy.net.

Winter Moon

MERCEDES LACKEY

TANITH LEE

C.E. MURPHY

CONTENTS

MOONTIDE

Mercedes Lackey

THE HEART OF THE MOON

Tanith Lee

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

BANSHEE CRIES

C.E. Murphy

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

MOONTIDE

Mercedes Lackey

Dedicated to my fellow “Lunatics” at www.LUNA-Books.com, without whom I would be a great deal less sane

Dear Reader,

The world I created for the Five Hundred Kingdoms stories is a place where fairy tales can come true—which is not always a good thing. But it is important to remember that most people living in this world go about their lives blissfully unaware of the force that I call “The Tradition” and its blind drive to send certain lives down predestined paths. As long as their lives are not touched by The Tradition, as long as they do not find themselves replicating the story of some tale, song or myth, most people go about their business never even guessing that such a force exists.

Such are the characters in this story, “Moontide.” There is no mention of The Tradition, nor of fairy godmothers. These folks have magic, indeed, but it is small magic for the most part. Do not underestimate the small magics, however. A great deal can be done with a very little magic at the right time and place. And even more can be done with a heart full of courage, and someone you can trust at your side.

Sincerely,

Mercedes Lackey

Lady Reanna watched with interest as Moira na Ferson took her chain-mail shirt, pooled it like glittery liquid on the bed, and slipped it into a grey velvet bag lined with chamois. It was an exquisitely made shirt; the links were tiny, and immensely strong; Moira only wished it was as featherlight as it looked.

“Your father doesn’t know what he’s getting back,” Reanna observed, cupping her round chin with one deceptively soft hand, and flicking aside a golden curl with the other.

“My father didn’t know what he sent away,” Moira countered, just as her heavy, coiled braid came loose and dropped down her back for the third time. With a sigh, she repositioned it again, picked up the silver bodkin that had dropped to the floor, and skewered it in place. “He looked at me and saw a cipher, a nonentity. He saw what I hoped he would see, because I wanted him to send me far, far away from that wretched place. Maybe I have my mother’s moon-magic, maybe I’m just good at playacting. He saw a little bit of uninteresting girl-flesh, not worth keeping, and by getting rid of it he did what I wanted.” Candle- and firelight glinted on the fine embroidered trim of an indigo-colored gown, and gleamed on the steel of the bodice knife she slipped into the sheath that the embroidery concealed.

“But to send you here!” Reanna shook her head. “What was he thinking?”

“Exactly nothing, I expect.” Moira hid her leather gauntlets inside a linen chemise, and inserted a pair of stiletto blades inside the stays of a corset. “I’m sure he fully expected to have a half-dozen male heirs by now, and wanted only to find somewhere to be rid of me at worst, and to polish me up into a marriage token at best. He looked about for someone to foist me off on—which would have to be some relation of my mother’s, since he’s not on speaking terms with most of his House—and picked the one most likely to turn me into something he could use for an alliance. You have to admit, the Countess has a reputation for taking troublesome young hoydens and turning out lovely women.” The ironic smile with which she delivered those last words was not lost on her best friend. Reanna choked, and her pink cheeks turned pinker.

“Lovely women who use bodkins to put up their hair!” she exclaimed. “Lovely women who—”

“Peace,” Moira cautioned. “Perhaps the moon-magic had a hand in that, too. If it did, well, all to the good.” An entire matched set of ornate silver bodkins joined the gauntlets in the pack, bundled with comb, brush, and hand mirror. “There can be only one reason why Father wants me home now. He plans to wed me to some handpicked suitor. Perhaps it’s for an alliance, perhaps it’s to someone he is grooming as his successor. In either case, though he knows it not, he is going to find himself thwarted. I intend to marry no one not of my own choosing.”

Reanna rested her chin on her hands and looked up at Moira with deceptively limpid blue eyes. “I don’t know how you’ll manage that. You’ll be one young woman in a keep full of your father’s men.”

“And the law in Highclere says that no woman can be wed against her will. Not even the heir to a sea-keep. And the keep will be mine, whether he likes it or not, for I am the only child.” Moira rolled wool stockings into balls and stuffed them in odd places in the pack. She was going to miss this cozy room. The sea-keep was not noted for comfort. “I will admit, I do not know, yet, what I will do when he proposes such a match. But the Countess has not taught me in vain. I will think of something.”

“And it will be something clever,” Reanna murmured. “And you will make your father think it was all his idea.”

Moira tossed her head like a restive horse. “Of course!” she replied. “Am I not one of her Grey Ladies?”

Moira’s midnight-black braid came down again, and she coiled it up automatically, casting a look at herself in the mirror as she did so. As she was now—without the arts of paint and brush she had learned from Countess Vrenable—no man would look twice at her. This was a good thing, for a beauty had a hard time making herself plain and unnoticed, but one who possessed a certain cast of pale features that might be called “plain” had the potential to be either ignored or to make herself by art into a beauty. Strange that she and Reanna should have become such fast friends from the very moment she had entered the gates of Viridian Manor. She, so dark and pale, and Reanna, so golden and rosy—yet beneath the surface, they were very much two of a kind. Both had been sent here by parents who had no use for them; daughters who must be dowered were a liability, but girls schooled by Countess Vrenable had a certain cachet as brides, and often the King could be coaxed into providing an addition to an otherwise meager dower. Especially when the King himself was using the bride as the bond of an alliance, which had also been known to happen to girls schooled by the Countess. Both Moira and Reanna were the same age, and when it came to their interests and skills, unlikely as it might seem, they were a perfectly matched set.

And both had, two years ago, been taken into the especial schooling that made them something more than the Countess’s fosterlings. Both had been invited to become Grey Ladies.

It sometimes occurred to Moira that the difference between girls fostered with Countess Vrenable and those fostered elsewhere, was that the other girls went through their lives assuming that no matter what happened, no matter what terrible thing befell them, there would be a rescue and a rescuer. The Grey Ladies knew very well that if there was a rescue to be had, they would be doing the rescuing themselves.

There was a great deal to be said for not relying on anyone but yourself.

“You’re not a Grey Lady yet,” Reanna reminded her, from her perch on the bolster of the bed. “That’s for the Countess to decide.”

A polite cough beside them made them both turn toward the door. “In fact, my dear, the Countess is about to make that decision right now.”

No one took Countess Vrenable, first cousin to the King, for granted. And it was not only because of her nearness in blood to the throne. She was not tall, yet she gave the impression of being stately; she was no beauty, yet she caused the eyes of men to turn away from those who were “mere” beauties. It was said that there was no skill she had not mastered. She danced with elegance, conversed with wit, sang, played, embroidered—had all of the accomplishments any well-born woman could need. And several more, besides. Her hair was pure white, yet her finely chiseled face was ageless. Some said her hair had been white for the past thirty years, that it had turned white the day her husband, the Count, died in her arms.

“You are a little young to be one of my Ladies, child,” the Countess said, in a tone that suggested otherwise. “However, this move on your father’s part holds…potential.”

The older woman turned with a practiced grace that Moira envied, and began pacing back and forth in the confined space of the small room she shared with Reanna. “I should tell you a key fact, my dear. I created the Grey Ladies after my dear husband died, because it was lack of information that caused his death.”

She paused in her pacing to look at both girls. Reanna blinked, looking puzzled, but too polite to say anything.

The Countess smiled. “Yes, my children, to most, he died because he threw himself between an assassin and the King. But the King and I realized even as he was dying that the moment of his death began long before the knife struck him. We know that if we had had the proper information, the assassin would never have gotten that far. Assassins, feuds, even wars—all can be averted with the right information at the right time.” She passed a hand along a fold of her sable gown. “My cousin has kept peace within our borders and without because he values cunning over force. But it is a never-ending struggle, and in that struggle, information is the most powerful weapon he has.”

As Reanna’s mouth formed a silent O, the Countess turned to Moira. “Here is the dilemma I face. There is information that I need to know in, and about, the Sea-Keep of Highclere and its lord. But conflicting loyalties—”

Moira raised an eyebrow. “My lady, I have not seen my father for more than a handful of days in all my life. I know well that although my mother loved him, he wedded her only to have her dower, and it was her desperate attempt to give him the male heir he craved that killed her. He cast me off like an outworn glove, and now he calls me back when he at last has need of me. I have had more loving kindness from you in a single day than I have had from him in all my life. If he works against the King, it is my duty to thwart him.” She met the Countess’s intensely blue eyes with her own pale grey ones. “There are no conflicting loyalties, my lady. I owe my birth to him—but to you, I owe all that I am now.”

What she did not, and would not say, was a memory held tight within her, of the night her mother had died, trying to give birth to the male child her father had so desperately wanted. How her mother lay dying and calling out for him, while he had eyes only for the son born dead. How he had mourned that half-formed infant the full seven days and had it buried with great ceremony, while his wife went unattended to her grave but for Moira and a single maidservant. She had never forgiven him for that, and never would.

The Countess held herself very still, and her eyes grew dark with sadness. “My dear child, I understand you. And I am sorry for it.”

Reanna sighed. “Not all of us are blessed with loving parents, my lady,” she said.

The Countess’s lips thinned. “If you had loving parents, child, I would be the last person to remove you from their care,” she replied briskly, and Moira suddenly understood why she felt she had joined some sort of sisterhood when she came to foster under the Countess’s care. None of them had been considered anything other than burdens at worst, and tokens of negotiation at best, by their parents.

Which makes us apt to trust the first hand that offers kindness instead of a blow, she thought. Which was, of course, a thought born of the Countess’s own training. The Countess taught them all to look for weaknesses and strengths, and to never accept anything at its face value, even the girls who were not recruited into the ranks of the Grey Ladies.

But then her mind added, And it is a very good thing for all of us that milady is truly kind, and truly cares. Because she had no doubt of that. The Countess cared deeply about her fosterlings, whether they were Grey Ladies or not.

But it did make her wonder what someone with less scruples could accomplish with the same material to work on.

“Would that I had a year further training of you, Moira,” the Countess said, frowning just a little. “I am loath to throw you into what may be a lion’s den with less than a full quiver of arrows.”

“I am thrown there anyway,” Moira replied logically. “My father will have me home, and you cannot withhold me. I would as soon be of some use.” And then something occurred to her, which made the corners of her mouth turn up. “But I shall want my reward, my lady.”

“Oh, so?” The Countess did not take affront at this. One fine eyebrow rose; that was all.

“Should I find my father in treason, his estates are confiscated to the Crown, are they not?” she asked. “Well then, as we both know, your word is as good as the King’s. So should information I lay be the cause of such a finding, I wish your hand and seal upon it that the Sea-Keep of Highclere, my mother’s dower, remains with me.”

Slowly, the Countess smiled; it was, Moira thought, a smile that some men might have killed for, because it was a smile full of warmth and approval. “I have taught you well,” she said at last. “Better than I had thought. Well enough, my hand and seal on it, and if you can think thus straightly, I believe you may serve your King.” And she took pen and parchment from the desk and wrote it out. “And you, Reanna—you may hold this in surety for your friend,” she continued, handing the parchment to Reanna, who waved it in the air to dry. “I think it best that you, Moira, not be found with any such thing on your person.”

Moira and Reanna both nodded. Moira, because she knew that no one would be able to part Reanna from the paper if Reanna didn’t wish to give it up. Reanna—well, perhaps because Reanna knew that the Countess would never attempt to take it from her.

“All right, child,” the Countess said then. “I am going to steal you away from your packing long enough to try and cram a year’s worth of teaching into an afternoon.”

In the end, the Countess took more than an afternoon, and even then, Moira felt as if her head had been packed too full for her to really think about what she had learned.

The escort that her father had sent had been forced to cool its collective heels until the Countess saw fit to deliver Moira into their hands. There was not a great deal they could do about that; the Countess Vrenable outranked the mere Lord of Highclere Sea-Keep. The Countess was not completely without a heart; she did see that they were properly fed and housed. But she wanted it made exquisitely clear that affairs would proceed at her pace and convenience, not those of some upstart from the costal provinces.

But there was more here than the Countess establishing her ascendancy, for the lady never did anything without having at least three reasons behind her action. The Countess was also goading Lord Ferson of Highclere Sea-Keep, seeing if he could be prodded into rash behavior. Holding on to Moira a day or two more would be a minor irritation for most fathers, especially since his men had turned up unheralded and unannounced. In fact, a reasonable man would only think that the Countess was fond of his daughter and loath to lose her. But an unreasonable man, or a man hovering on the edge of rebellion, might see this as provocation. And he might then act before he thought.

As a consequence, Moira had more than enough time to pack, and she had some additions, courtesy of the Countess, to her baggage when she was done.

In the dawn of the fourth day after her father’s men arrived with their summons, she took her leave of Viridian Manor.

As the eastern sky began to lighten, she mounted a gentle mule amid her escort of guards and the maidservant they had brought with them. She took the aid offered by the chief of the guardsmen; not that she needed it, for she could have leaped astride the mule without even touching foot to stirrup had she chosen to do so—but from this moment on, she would be painting a portrait of a very different Moira from the one that the Countess had trained. This Moira was quiet, speaking only when spoken to, and in all ways acting as an ordinary well schooled maiden with no “extra” skills. The rest of her “personality” would be decided when Moira herself had more information to work with. The reason for her abrupt recall had still not been voiced aloud, so until Moira was told face-to-face why her father had summoned her, it was best to reveal as little as possible.

That said, it was as well that the maid was a stranger to her; indeed, it was as well that the entire escort was composed of strangers. The fewer who remembered her, the better.

This was hardly surprising; she had been a mere child when she left, and at that time she hadn’t known more than a handful of her father’s men-at-arms by sight. She had known more of the maidservants, but who knew if any of them were still serving? Two wives her father had wed since the death of her mother; neither had lasted more than four years before the harsh winters of Highclere claimed them, and neither had produced another heir.

Of course, father’s penchant for delicate little flowers did make it difficult for them. Tiny, small-boned creatures scarcely out of girlhood were his choice companions, timid and shy, big eyed and frail as a glass bird. Moira’s mother had looked like that—in fact, if she hadn’t wed so young (too young, Moira now thought) she might have matured into what Moira was now—ethereal in appearance, but tough as whipcord inside.

She felt obscurely sorry for those dead wives. She hadn’t been there, and she didn’t know them, but she could imagine their shock and horror when confronted by the winter storms that coated the cliffs and the walls of the keep with ice a palm-length deep. She was sturdier stuff, fifteen generations born and bred on the cliffs of Highclere, like those who had come before her. Pale and slender she might be, but she was tough enough to ride the day through and dance half the night afterward. So her mother still would be, if she’d had more care for herself.

The maidservant was up on pillion behind one of the guards. There were seven of them, three to ride before, and three to ride behind, with the seventh taking the maid and Moira on her mule beside him. They seemed competent, well armed, well mounted; not friendly, but that would have been presumptuous.

She looked up at the sky above the manor walls as they loaded her baggage onto the pack mule, and sniffed the air. A few weeks ago, it had still been false summer, the last, golden breath of autumn, but now—now there was that bitter scent of dying leaves, and branches already leafless, which told her the season had turned. It would be colder in Highclere. And in another month at most, or a week or two at worst, the winter storms would begin.

It was a strange time for a wedding, if that was what she was being summoned to.

“Are you ready, my lady?”

She glanced down at the guard at her stirrup, who did not wait for an answer. He swung up onto his horse and signaled to the rest of the group, and they rode out without a backward glance. Not even Moira looked back; she had said her farewells last night. If her father’s men were watching, let them think she rode away from here with no regret in her heart.

They thought she rode with her eyes modestly down, but she was watching, watching everything. It was a pity she could not simply enjoy the ride, for the weather was brisk without being harsh, and the breeze full of the pleasant scents of frost, wood smoke, and occasionally, apples being pressed for cider. The Countess’s lands were well situated and protected from the worst of all weathers, and even in midwinter, travel was not unduly difficult. The mule had a comfortable gait to sit, and if only she had had good company to enjoy it all with, the trip would have been enchanting.

The guards were disciplined but not happy. They rode without banter, without conversation, all morning long. And it was not as if the weather oppressed them, because it was a glorious day with only the first hints of winter in the air. As they rode through the lands belonging to Viridian Manor, there were workers out harvesting the last of the nuts, cutting deadfall, herding sheep and cattle into their winter pastures, mostly singing as they worked. The air was cold without being frigid, the sky cloudless, the sun bright, and the leaves that littered the ground still carried their vivid colors, so that the group rode on a carpet of gold and red. There could not possibly have been a more glorious day. And yet the guards all rode as if they were traveling under leaden skies through a lifeless landscape.

They stopped at about noon, and rode on again until dark. In all that time, the guards exchanged perhaps a dozen words with her, and less than a hundred among one another. But when camp was made for the evening, the maid, at least, was a little more talkative. Lord Ferson had provided a pavilion for Moira to share with the maid; if it had been up to Moira, she would have been perfectly content to sleep under the moon and stars. She felt a pang as she stepped into the shelter of the tent, wishing she did not have to be shut away for the night.

She let the maid help her out of her overgown, and sat down on the folding stool provided for her comfort while the maid finished her ministrations. “I have not seen Highclere Sea-Keep in many years,” Moira said, in a neutral tone, as the maid brought her a bowl of the same stew and hard bread the men were eating. “Have you served the lord long?”

“Eight years, milady,” the maid said. She was as neutral a creature as could be imagined, with opaque brown eyes, like two water-smoothed pebbles that gave away nothing. She was, like nearly every other inhabitant of the lands in and around Highclere, very lean, very rangy, dark haired and dark eyed. The Sea-Keep had always provided its servants with clothing; hers was the usual garb of an upper maidservant in winter—dark woolen skirt, laced leather tunic, and undyed woolen chemise—and not the finer woolen overgown and bleached lamb’s wool chemise that Moira recalled her mother’s personal maidservant wearing. So her father had sent an upper maid, but not a truly superior handmaiden. This was not necessarily a slight; handmaidens tended to be young, were often pretty, and could be a temptation to the guards. This woman, old enough to be Moira’s mother, plain and commonplace, and entirely in control of herself and her situation, was a better choice for a journey.

“Has the keep changed much in that time?” Moira asked, as she finished her meal and set the bowl aside. It was a natural question, and a neutral one.

The woman shrugged as she took Moira’s braid down from its coil and began brushing it. Needless to say, the pins holding it in place were simple silver with polished heads, not bodkins. “The keep never changes,” she replied. “My lady has fine hair.”

“It is my one beauty,” Moira replied. “And my lord my noble father is well?”

“I am told he is never ill,” said the maid, concentrating on rebraiding Moira’s plaits.

Moira nodded; this woman might not be a superior lady’s maid, but she was not rough handed. “He is a strong man. The sea-keeps need strong hands to rule them.”

Bit by bit, she drew tiny scraps of information from the maid. It wasn’t a great deal, but by the time she slipped beneath the blankets of her sleeping roll, she began to have the idea that the people of Highclere Sea-Keep were not encouraged to speak much among themselves, and even less encouraged to speak to “outsiders” about what befell the keep. And that could be a sign that the lord of the sea-keep was holding a dark secret.

If so, then this was precisely what the Countess Vrenable of Viridian Manor wished to find out.

Highclere Sea-Keep was less than impressive from the road. In fact, very little of it was visible from the road.

The road led through what the local people called “forest.” These were not the tall trees that surrounded Viridian Manor; the growth here was windswept, permanently bent from the prevailing wind from the sea, and stunted by the salt. The forest didn’t change much, no matter what the season; it was mostly a dark, nearly black evergreen she had never seen anywhere else but on the coast. Though the trees weren’t tall, this forest hid the land-wall and gatehouse of the sea-keep right up until the point where the road made an abrupt turn and dropped them all on the doorstep.

And there was a welcome waiting, which Moira, to be frank, had not expected.

She had not forgotten what her home looked like, and at least here on the cliff, it had not changed. A thick, protective granite wall with never less than four men patrolling the top ran right up to the cliff’s edge, making it unlikely anyone could attack the keep from above. There was a gatehouse spanning both sides of the gate, which was provided with both a drop-down iron portcullis and a set of heavy wooden doors. Above the gate was a watch room connected with both gatehouses, which could be manned even when the worst of storms battered the cliff. Both the portcullis and the wooden doors stood open, and arranged in front of them was a guard of honor, eight men all in her father’s livery of blue and silver, with the Highclere Sea-Keep device of a breaking wave on their surcoats.

Moira dismounted from her mule—but only after waiting for the leader of the honor guard to help her. He bowed after handing her down from the saddle, as the sea wind swept over all of them, making the pennants on either tower of the gatehouse snap, and blowing her heavy skirts flat against her legs.

There was ice in that wind, and the promise that winter here was coming early, a promise echoed by the fact that the trees that were not evergreens already stretched skeletal, bare limbs to the sky.

“Welcome home, Lady Moira,” the leader of the guard said, bowing a second time. “The Lord Ferson awaits you in the hall below.”

“Then take me to him immediately,” she said, dropping her eyes and nodding her head—but not curtsying. The head of the honor guard, a knight by his white belt, was below her in status. She should be modest, but not give him deference. This was one of the many things she should have learned—and of course, had—under anyone’s fosterage. She had no doubt that this knight would be reporting everything he saw to her father, later.

The knight offered her his arm, and she took it. Most ladies would need such help on the rest of the journey. She and the knight led the way through the gates, with the honor guard falling in behind; the maid and her journey escort brought up the rear.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.