Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

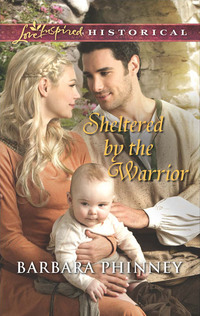

Czytaj książkę: «Sheltered by the Warrior»

Her unexpected guardian

Baron Stephen de Bretonne’s sworn duty is to serve the king—and that means finding the Saxons plotting against the throne by any means necessary. Protecting a Saxon woman and her half-Norman child? Merely a means to that end. But the lovely Rowena proves to be more than just a pawn in his plan. And his admiration for her could ruin everything if he can’t stifle his feelings.

While Rowena must begrudgingly accept Norman protection for herself and her baby, she knows better than to trust any man. Yet in the face of danger, can she also open her heart to her unlikely protector?

“So, tell me, how did you end up in Dunmow, as guest of my friend Lord Adrien?”

Rowena remained stiff. Finally, she said, “I was not his guest, milord.”

Then, from within the hut, a babe cried loudly. Lifting the damp hem of her cyrtel, Rowena swung past him, and Stephen reached forward to open the door for her.

She flinched at his raised arm. Rowena was scared. Hurt, also, but mostly frightened. Stephen stepped aside as she ducked into the hut.

Wandering from the door, Stephen looked again at the vandal’s work. The cur had crushed an egg, had laid waste to late season herbs and had trampled the roots under his boots. Saxon boots. The simple style was unmistakable.

Why would a Saxon destroy this young woman’s food stocks? Because she was rumored to have allied herself with the Normans? It had been two years since William’s victory at Hastings. This Rowena would have been barely into womanhood back then.

The door behind him opened again. Stephen turned to watch Rowena step outside with a babe in her arms.

The babe had dark hair and olive skin—the father could not possibly be Saxon.

His heart sank. So that was how she was aligned with the Normans.

BARBARA PHINNEY was born in England and raised in Canada. After she retired from the Canadian Armed Forces, Barbara turned her hand to romance writing. The thrill of adventure and the love of happy endings, coupled with a too-active imagination, have merged to help her create this and other wonderful stories. Barbara spends her days writing, building her dream home with her husband and enjoying their fast-growing children.

Sheltered by the Warrior

Barbara Phinney

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

Or simply visit

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

And straightway the father of the child cried out, and said with tears, Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief.

—Mark 9:24

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

Introduction

About the Author

Title Page

Bible Verse

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Dear Reader

Extract

Copyright

Chapter One

Kingstown, Cambridgeshire, England Autumn, 1068 AD

She will surely starve this winter.

The mists of the early morning lingered as Rowena stepped from her hut and found herself staring at the plunder around her. Little Andrew hadn’t yet awakened, so she’d taken this time to pray, as her friend, Clara, had once suggested.

Her shaking hand found the door and she shut it quietly. Her other hand grasped the cut ends of the thin thatch that reached from the roof peak almost to the ground. In this village, ’twas cheaper to grow thatch for roofs than to make daub for walls, so the hut’s walls were short, barely coming to her shoulders. Only those in the manor house were rich enough to have fine, straight walls that reached two stories up to the thick, warm thatch above.

Stepping forward, Rowena gaped at the devastation around her. How could someone have ruined her harvest? And in the middle of the night? Aye, the villagers gave her the cold shoulder, but to move to such destruction? Why?

Gasping, she tossed off the hood of her cloak and forced the crisp air into her lungs to conquer the wash of panic. Last night, when she’d locked up for the evening, she’d wondered if there would be a killing frost, but had remembered with gratitude that she had a good amount of roots dug and neatly stored under mounds of straw, and enough herbs drying to make strong pottages. With the pair of rabbits and the hen Lady Ediva had given her, she’d truly believed that she and her babe would not just survive the winter, but mayhap even flourish.

Nay, this cannot be happening!

Rowena bit back tears as she stepped toward what was left of her garden. The heavy dew soaked through her thin shoes, and her heart hung like the wet hem of her cyrtel and cloak. All her hard work of collecting herbs and gathering straw and burying roots in frost-proof mounds was for naught.

As she looked to her right, wisps of her pale hair danced across her cheek. Both the rabbit hutch and henhouse had been torn apart, the animals long gone. Someone had wrenched off the doors and crushed the early morning’s egg beneath the hard heel of a heavy boot. Chicken feathers flipped in the misty breeze.

She hadn’t heard a thing, but since her babe had begun to sleep through the night and her days were long, she was oft so exhausted that sleep held her till morn. Hastily, she scanned her garden, her eyes watchful for movement, her ears pinned to hear any soft clucking of a distressed hen. Nothing, not a breath of life amid the shredded vegetation.

“Nay,” she whispered in the cold air, “come back, little hen. You’re safe now.”

No answer. Just a ruined cage. But that was fixable, at least. Clara, who’d left yesterday to return to her own home, had shown her how to weave various plant stalks into strong netting. Being a fisherman’s daughter, Clara knew these things.

Rowena already knew how to soak and shred the leftover stalks until the soft fibers could be spun into threads. She’d seen her older sister weave cloth that way and looked forward to making baby clothes this winter, for Andrew was growing fast and she had no one to offer her their children’s castoffs.

At the thought of her family, a knot of bitterness choked her. Rowena tried to swallow it, for Clara had warned that bitterness caused all measure of illness. But ’twas hard to forget the fact that she had no kin willing to help her. ’Twas hard to forget that her parents had sold her as a slave to a Norman baron, ridiculously boasting that her pale hair and eyes were a promise of many strong sons within her.

Nay, she thought with watering eyes, ’twas hard to forget that the baron had then tried to murder her and steal the son she’d birthed, as part of a plot so villainous it still terrified her.

And the men in Colchester, the town to which she’d fled, had no wish to defend her. They’d wanted her along with Clara to leave and take their troubles with them. So she’d left. Now here in Kingstown, she knew that heartache and pain had followed her.

Rowena looked toward the sun that strained to pierce the rising mists. Lord God, Clara says You’re up there. Why are You doing this to me? Are You making me suffer for not knowing You all these years? I know You now.

When she received no answer, Rowena set her shoulders and pursed her lips. She’d resettled in this village, been given her freedom and a hut that had with it a decent, albeit overgrown, garden. Clara had brought with her some provisions from Dunmow and had offered Rowena a final prayer to start her new life. ’Twould be difficult for her as a woman without a husband, and a babe too small to help, but Rowena had been determined to succeed.

She’d thought she would do well.

But now? She peered again at the ruined henhouse. Each day she’d found that one egg brought joy, and she’d offered thanks to God for it. A hope of a new life.

Not so anymore. The fair-headed Saxon villagers here had taken one look at Andrew and his mixed heritage and prejudged her. She’d heard the whispered words: “Traitor.” “Spy.” “Prostitute.” They didn’t even care to ask for the truth.

Rowena stifled a cry as she turned her gaze back to her garden. All the roots she’d stored in a straw-covered mound were scattered, snapped or crushed to a useless pulp by heavy boots. Nay, only one certainty settled over the awful, angry scene.

Someone wanted her to starve this winter.

* * *

Stephen de Bretonne accepted the reins of his courser and swung his leg up and over the saddle to mount the large chestnut beast. The mail of his hauberk chinked as he settled down. The horse stirred, expecting battle, or at least a good run, but Stephen kept the reins tight as he turned around to survey his village. Kingstown looked peaceful, very different from the politically charged dangers that flowed through the court in London.

Ha! Despite the gentle morning here at his holding, Stephen knew the lifting mist and soft dew masked the day’s intrigue. These villagers could rival even the suspicious courtiers in Lon—

“Milord?”

Stephen snapped his attention to his young squire, a boy named Gaetan. The boy offered up a dagger. Reluctantly, he took the extra weapon. Wasn’t it bad enough that he needed to carry his long sword each day? And now a dagger for extra measure? Beside him, atop another stallion, one of his own guards also accepted a dagger from a second young squire. With a scowl, Stephen led his mount from the stables. Along with other villages, this estate had been his reward for his bravery at Hastings, two years before.

Ha! What was bravery on the field at Hastings, when a man could not even save his own brother? Corvin had fought alongside him there, but one moment of distraction on Stephen’s part and suddenly Corvin was dead.

And shortly after, King William had bestowed on Stephen many estates. Corvin should have been the one to receive them. He’d fought boldly until the end.

Now Stephen had more than enough land. With a tight jaw, he shoved the remorse back where it could not sting him, for the work ahead required his full attention.

He kept the seat of his holdings here in Kingstown, for none of the others had a manor house. Now he put his home behind him as he trotted along the road leading through the village, his sword scraping his saddle on one side, his dagger snug on the other. His chain mail sat heavy on his shoulders, as if expecting a battle instead of the quiet mists of morning.

Stephen was not afraid of fighting, for such was a part of his soldiering life. But he was not here for battle. His was a shrewder reason—to seek out those local agitators who would defy the king.

When William had ordered the task, Stephen had accepted it with a flick of his hand, but he’d soon learned ’twould not be easy. At court, he’d enjoyed the sly machinations of those who would try to outmaneuver King William, but here, the Saxons were craftier, feigning ignorance and hiding the troublemakers who oft taxed his soldiers to exhaustion. He was sick of Saxons, each pale face hiding secrets. For all he knew, one of these men had been the one to deal Corvin his fatal blow. Aye, the chances were slim, but they still remained.

Stephen felt the expected wash of terrible memory. ’Twas as if the moment Corvin died had been winked out, replaced by a blur and then a stretch of time where all Stephen saw was Corvin on the ground.

And in the weeks and months after, word reached him of their mother’s reaction. Her accusing words to him still tore his heart. He’d lost both his brother and his mother that day at Senlac.

Nay, enough! There were chores to do.

And checking the defenses each morning he was here in Kingstown had become a distasteful chore. But King William was due to visit before winter, and Stephen knew his liege would order an embankment and palisade be cut through the forest to the north. ’Twould not be a popular command, and Stephen would not impose the task on the villagers yet, for they needed to finish storing their provisions for winter. But ’twould have to be started soon.

“Which way, milord?” the guard asked, pulling his horse up beside Stephen.

“’Tis my first day back and I must inspect it all.” Stephen had been in London all summer, leaving this estate in his sister’s capable hands. “It makes no difference. To the north, I suppose.” Always the most unpleasant task first. There, the village wrestled constantly with the encroaching forest. Beyond it, the land dipped into the marshes and fens that reached all the way to Ely. Another backwater full of dissidents.

As he and his guard walked the horses, the mists rose to block the sun, and the day grew duller. Disgusted, Stephen spurred his horse to a trot through the thinnest portion of Kingstown. Ahead stood the village fence, the dilapidated weave of wattle designed to hold back marauders from the north. It sagged, rotting where it flopped into low spots. William would take one look at it and demand it be replaced immediately. Mayhap the trees cut to create a palisade could be used to—

Movement beyond the fence caught Stephen’s eye, and he reined his horse back to a walk. Wisps of silver-blond hair danced in the light breeze as a woman stooped to lift something from her garden. With an almost forlorn air, her small hut stood behind her. The woman dipped again and her pale hair flipped like a feather in a breeze.

’Twas too early for anyone to be roused. Stephen had already noted that these Saxons preferred to sleep in on the misty days that hinted of winter. So what was the woman doing at this hour?

He halted his horse at the gate as the guard leaned forward in his own saddle to flip open the latch. All the while, Stephen remained stock-still, entranced by the woman’s hair. ’Twas so unique a color, he would not have believed it existed if he’d only been told of it. But she was quite real, standing bareheaded in her garden, her whole demeanor one of sadness, like one of those minstrel girls who visited the king’s court to entertain with songs of lost love.

“Milord?” his guard prompted him quietly.

Something squeezed Stephen’s heart, but he ignored the odd sensation. He hadn’t been given Kingstown and its manor because he was an emotional clod. This village lay directly in the path between London and the rebellious north. A calculating tactician was needed here to draw out instigators who would bring down more from Ely. Extra troops would help, aye, but such had been discussed already in London, to no avail. They were still needed elsewhere.

Nay, until Stephen had eliminated all malcontents who would threaten the king’s sovereignty, any softness of heart could get him murdered, and ’twas best ignored.

Still curious, though, he swung off his horse and walked through the gate toward the woman. Ah, this must be Rowena, the woman who’d taken this hut. His friend Lord Adrien had sent him a missive asking if he could find a home for her here. Only the hut beyond the fence had been vacant. Its proximity to the forest made it undesirable, for everyone knew the woods harbored thieves and criminals, worse than those who lived in the village.

Having been in London when Adrien’s request arrived, Stephen had dispatched his brother-in-law, Gilles, to handle the issue of land and hut, and to set out the terms of tenancy. All he’d heard of this Rowena was that she’d been a slave, made free by order of the king himself, and that her rent for the next year had been paid in full by Adrien.

As Stephen passed his guard, the man dismounted, also. “’Tis the woman Rowena, milord.”

“I know of her. I should like to meet her.”

“She is of ill repute, sir,” the guard warned.

Stopping, Stephen shot the man a surprised look. “Why?”

“The villagers say she’s allied herself with us Normans. Did not Lord Adrien pay for her to be here?”

With a brief laugh, Stephen rolled his eyes, remembering one short conversation he’d had with his friend this past summer. “That means nothing. Lord Adrien is generous to all Saxons because he’s besotted with his Saxon wife.” Stephen shook his head, then peered again at the woman. “What is she doing?”

The guard stepped forward. “I will find out, milord.”

Hand raised, Stephen stopped him. “Nay. I will. ’Tis time to introduce myself.”

“Milord, she’s Saxon and not to be trusted. For all we know, she’ll sink a dagger into your heart the moment you speak to her.”

Chuckling, Stephen touched his chain mail. “Yet she allied herself with us? You make no sense, soldier. Besides, the woman is barely out of girlhood and she’s far too skinny to have enough strength to pierce my mail. Ha, if I were fearful of every Saxon, I would not leave my bedchamber. The king gave me this holding to—” He stopped. ’Twould not do well to say the king’s reasons for bringing him here. He continued, “I should at least meet all of this village’s inhabitants.”

Without waiting for an answer, Stephen strode up the lane toward her. The guard led the horses, but Stephen also heard the slow scrape of steel leaving a scabbard. The man had freed his sword.

Stephen’s courser whinnied loudly at the sound so akin to war. And at both harsh noises, the woman ahead spun. Again, Stephen was struck by her hair as it flowed with her movement. Aye, Saxons were towheaded, thanks to their northern ancestry, but never had he seen hair so free and so pale. This Rowena hadn’t even braided it yet, something that would have appalled his mother.

She looked up at him and he found her eyes were almost too light to look upon. A blue as delicate as in the stained-glass window in his home church in Normandy. Stephen watched her body tense. She twisted the broken root she held into a deadly grip one might reserve for a dagger.

“Planning to bury that parsnip in my chest?” asked Stephen as he opened the short gate of the hut’s small fence. Then he halted, shocked at the disarray. The pen at the far end had been tossed on its side, its door hanging by one hinge. Roots and vegetables were strewn about, some crushed as if a furious giant of lore had turned his wrath upon this garden.

Rowena said nothing, only keeping her grip on the parsnip tight as she backed away. Immediately, Stephen regretted his sharp tongue. He had no desire to frighten her.

Still in English, he tried a lighter tone. “’Tis not the best way to preserve your crops for winter, or to keep your fowl from escaping.”

She tossed the root onto the ground. “You think I do not know this?”

“An animal in the night?”

“Ha! Only one who wears boots,” she snapped. She quickly brushed the back of her hand across her glistening cheek, leaving a smudge of tear-dampened dirt in its wake.

“Who did this? Did you see them?” Stephen asked.

“Nay. I heard nothing, so they must have done this late into the night. Cowards!”

Stephen stepped gingerly around the garden, close to the door of her hut, to survey the mess. “Why would anyone do such a thing?”

Rowena said nothing. Stephen watched her. Though silent, she carried a wealth of information in the way she stood. She knew the reason for this vandalizing, he was sure. “Have you any enemies?” he asked.

She stiffened. “I should not have any! I have been here a month at best, and tried to speak with the other women, only to be treated like an outcast. That I can deal with, but this? I shall surely starve this winter because of their evil!” Her voice hitched slightly.

“I’ll see to it that doesn’t happen.”

“Who are you that—” Her gaze flew up and then narrowed. “You’re Baron Stephen.” Rowena’s cold whisper scratched like brambles, leaving it to feel more of an accusation than a statement.

“Aye. And you are Rowena, late of Dunmow.”

“I did not live in Dunmow. I came from a farm in the west, near Cambridge.”

Relatively close. Stephen pursed his lips. Most of this county had suffered greatly under William’s scorched-earth policies when he’d marched north to fight after taking London. But Cambridge had fared moderately better, for ’twas nothing but a backwater village as rude as any wild moor that lay to the south. Though the manor houses in the king’s path had been razed and the holdings would suffer much for years to come, the most isolated farmers, those with little contact with civilization, had escaped total destruction. Had she come from one of them?

Rowena threw her arms out to the mess around them. “We Saxons live hand to mouth here, barely affording a grain of barley. You offer food where you should be finding who did this!”

Aye, ’twas exactly his reason for being here. “’Twill be easy enough to discover. My experience in London has taught me several techniques of extracting the truth.”

She gasped. His calm answer was guileless, although he was not one to employ brutal punishment to acquire information. ’Twas better to keep one’s eyes and ears open and, for the most part, one’s mouth shut. A calm manner was more apt to lure out subterfuge than a harsh beating.

“So, tell me, how did you end up in Dunmow, as guest of my friend Lord Adrien?”

Rowena remained stiff. The breeze dropped and her hair fell, a single flaxen curtain of sword-straight locks. She went still, and if ’tweren’t for the light breath that streamed from her lips, he’d have thought she’d turned to stone. Finally, she said, “I was not his guest, milord.”

Stephen didn’t want to know what she wasn’t. Odd that she wouldn’t answer his question directly. Was there a hidden reason, or was he seeing intrigue where only shadows of Saxon distrust lay?

Then, from within the hut, a babe cried loudly. Lifting the damp hem of her cyrtel, Rowena swung past him, her chin tipped up and her mouth tight. Her eyes, too wide set and too large for her face, turned icy blue, adding to the chill of the morning. Yet, by their sheer size alone, they offered only innocence.

Stephen reached forward to open the door for her. ’Twas not required, but his mother’s training had been drilled into him long before his promotion to baron.

She flinched at his raised arm. ’Twas merely a blink and a slight jerk back, and so swift he would have missed it had his gaze not been sealed to her face.

Then ’twas gone, replaced by wariness. But he knew what he saw, and though not uncommon in a land where women had few rights, he disliked seeing fear in any woman’s eyes.

Aye, Rowena was scared. Hurt, also, but mostly frightened. Stephen stepped aside as she ducked into the hut, her cloak wafting out as she passed. The youthful screams within were soon replaced by soothing murmurs.

Wandering from the door, Stephen looked again at the vandal’s work. He bent several times to study and measure the boot prints he spied, while noticing their tread. The clear imprints of heavy boots all the same size told him that only one man had done this. The cur had crushed an egg, had laid waste to late-season herbs and had trampled the roots until they were completely inedible. Not just any man’s boots, Stephen noted as he straightened again. A Saxon man’s boots. The simple style was unmistakable.

Why would a Saxon destroy this young woman’s food stocks? Because she was rumored to have allied herself with the Normans? She was far too young for such subterfuge. It had been two years since William’s victory at Hastings. This Rowena would have been barely into womanhood back then. But still, a Saxon? One from the village, too, for the boot prints retreated toward the huts rather than disappearing into the forest to the north. This attack made no sense.

The door behind him opened again. Stephen turned to watch Rowena step outside with a babe in her arms.

The babe had dark hair and olive skin, and only one lineage with men of that complexion was in England right now. For some reason, his heart sank.

So that was how she was aligned with the Normans.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.