Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

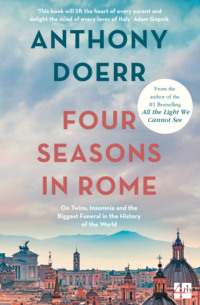

Czytaj książkę: «Four Seasons in Rome: On Twins, Insomnia and the Biggest Funeral in the History of the World»

Four Seasons in Rome

On Twins, Insomnia and the Biggest Funeral in the History of the World

Anthony Doerr

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

Originally published in the United States in 2007 by Scribner

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2008

This ebook edition published by 4th Estate in 2016

Copyright © Anthony Doerr 2007

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com

The right of Anthony Doerr to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © June 2010 ISBN: 9780007390533

Version: 2016-12-01

for Henry and Owen

Rain falls, clouds rise, rivers dry up, hailstorms sweep down; rays scorch, and impinging from every side on the earth in the middle of the world, then are broken and recoil and carry with them the moisture they have drunk up. Steam falls from on high and again returns on high. Empty winds sweep down, and then go back again with their plunder. So many living creatures draw their breath from the upper air; but the air strives in the opposite direction, and the earth pours back breath to the sky as if to a vacuum. Thus as nature swings to and fro like a kind of sling, discord is kindled by the velocity of the world’s motion.

PLINY THE ELDER, FROM THE

Natural History, AD 771

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

FALL

WINTER

SPRING

SUMMER

Notes

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Anthony Doerr

About the Publisher

FALL

ITALY LOOMS. WE MAKE CHECKLISTS—DIAPERS, CRIB bedding, a book light. Baby formula. Two dozen Nutri-Grain bars. We have never eaten Nutri-Grain bars in our lives, but now, suddenly, it seems important to have some.

I stare at our new Italian-to-English pocket dictionary and worry. Is “Here is my passport” in there? Is “Where for God’s sake can I buy some baby wipes?”

We pretend to be calm. Neither of us is willing to consider that tomorrow we’ll pile onto an Airbus with six-month-old twins and climb to thirty-seven thousand feet and stay there for fourteen hours. Instead we zip and unzip our duffels, take the wheels off the stroller, and study small, grainy photos of St. Peter’s on ricksteves.com.

Rain in Boise; wind in Denver. The airplane hurtles through the troposphere at six hundred miles per hour. Owen sleeps in a mound of blankets between our feet. Henry sleeps in my arms. All the way across the Atlantic, there is turbulence; bulkheads shake, glasses tinkle, galley latches open and close.

We are moving from Boise, Idaho, to Rome, Italy, a place I’ve never been. When I think of Italy, I imagine decadence, dark brown oil paintings, emperors in sandals. I see a cross-section of a school-project Colosseum, fashioned from glue and sugar cubes; I see a navy-blue-and-white soap dish, bought in Florence, chipped on one corner, that my mother kept beside her bathroom sink for thirty years.

More clearly than anything else, I see a coloring book I once got for Christmas entitled Ancient Rome. Two babies slurped milk from the udders of a wolf. A Caesar grinned in his leafy crown. A slinky, big-pupiled maiden posed with a jug beside a fountain. Whatever Rome was to me then—seven years old, Christmas night, snowflakes dashing against the windows, a lighted spruce blinking on and off downstairs, crayons strewn across the carpet—it’s hardly clearer now: outlines of elephants and gladiators, cartoonish palaces in the backgrounds, a sense that I had chosen all the wrong colors, aquamarine for chariots, goldenrod for skies.

On the television screen planted in the seat-back in front of me, our little airplane icon streaks past Marseilles, Nice. A bottle of baby formula, lying sideways in the seat pocket, soaks through the fabric and drips onto my carry-on, but I don’t reach down to straighten it for fear I will wake Henry. We have crossed from North America to Europe in the time it takes to show a Lindsay Lohan movie and two episodes of Everybody Loves Raymond. The outside temperature is minus sixty degrees Fahrenheit.

A taxi drops us in front of a palace: stucco and travertine, a five-bay façade, a staircase framed by topiaries. The gatekeeper stubs his cigarette on a shoe sole and says, in English, “You’re the ones with the twins?” He shakes our hands, gives us a set of keys.

Our apartment is in a building next to the palace. The front gate is nine feet tall and iron and scratched in a thousand places; it looks as if wild dogs have been trying to break into the courtyard. A key unlocks it; we find the entrance around the side. The boys stare up from their car seats with huge eyes. We load them into a cage elevator with wooden doors that swing inward. Two floors rattle past. I hear finches, truck brakes. Neighbors clomp through the stairwell; a door slams. There are the voices of children. The gate, three stories down, clangs hugely.

Our door opens into a narrow hallway. I fill it slowly with bags. Shauna, my wife, carries the babies inside. The apartment is larger than we could have hoped: two bedrooms, two bathrooms, new cabinets, twelve-foot ceilings, tile floors that carry noise. There’s an old desk, a navy blue couch. The refrigerator is hidden inside a cupboard. There’s a single piece of art: a poster of seven or eight gondolas crossing a harbor, a hazy piazza in the background.

The apartment’s jewel is a terrace, which we reach through a narrow door in the corner of the kitchen, as if the architect recognized the need for a doorway only at the last moment. It squats over the building’s entrance, thirty feet across, fifty feet up. From it we can look between treetops at jigsaw pieces of Rome: terra-cotta roofs, three or four domes, a double-decker campanile, the scattered green of terrace gardens, everything hazed and strange and impossible.

The air is moist and warm. If anything, it smells vaguely of cabbage.

“This is ours?” Shauna asks. “The whole terrace?” It is. Except for our door, there is no other entrance onto it.

We lower the babies into mismatched cribs that don’t look especially safe. A mosquito floats through the kitchen. We share a Nutri-Grain bar. We eat five packages of saltines. We have moved to Italy.

For a year I’ll be a fellow at the American Academy in Rome. There are no students here, no faculty, only a handful of artists and scholars, each of whom is given a year in Rome to pursue independent projects.

I’m a fellow in literature. All I have to do is write. I don’t even have to show anyone what I write. In return, they give me a studio, the keys to this apartment, two bath mats, a stack of bleached towels every Thursday, and $1,300 a month. We’ll live on the Janiculum Hill, a green wave of trees and villas that rears a few hundred yards and a series of centuries-old stone staircases above the Roman neighborhood called Trastevere.

I stand on a chair on the terrace and try to find the Tiber River in the maze of distant buildings but see no boats, no bridges. A guidebook at the Boise Public Library said Trastevere was charming, crammed with pre-Renaissance churches, medieval lanes, nightclubs. All I see is haze: rooftops, treetops. I hear the murmur of traffic.

A palm tree out the window traps the sunset. The kitchen faucet drips. We did not apply for this fellowship; we did not even know that it existed. Nine months ago we got a letter from the American Academy of Arts and Letters saying my work had been nominated by an anonymous committee. Four months later we got a letter saying we had won. Shauna was still in the hospital, our sons twelve hours old, when I stood in front of our apartment in the slush and found the envelope in the mail.

Our toilet has two buttons to flush it, one twice the size of the other. We discuss: I contend they produce the same amount of water; Shauna says the bigger button is for bigger jobs.

As it always is with leaving home, it is the details that displace us. The windows have no screens. Sirens, passing in the street, are a note lower. So is the dial tone on our red plastic telephone. When we pee, our pee lands not in water but on porcelain.

The bathroom faucets read C and F and the C is for calda, not cold but hot. The refrigerator is the size of a beer cooler. An unlabeled steel lever protrudes from the wall above the cooktop. For gas? Hot water?

The cribs the Academy has loaned us have no bumpers or sheets but do have what we decide must be pillows: inch-high rectangles of foam, sheathed in cotton.

The dishwashing soap smells like salted limes. The mosquitoes are bigger. Instead of closets, the bedrooms have big, musty wardrobes.

Shauna rummages through the triangular space that is to become our kitchen, dining room, and living room. “There’s no oven.”

“No oven?”

“No oven.”

“Maybe Italians don’t use ovens?”

She gives me a look. “They invented pizza.”

Fifteen minutes before midnight, the digital clock on the microwave reads 23:45. What will midnight be? 0:00?

That first night we go to sleep around midnight, but the boys are awake at one, crying in their strange cribs. Shauna and I pass each other in the hall, each rocking a baby.

Jet lag is a dryness in the eyes, a loose wire in the spine. Wake up in Boise, go to bed in Rome. The city is a field of shadows beyond the terrace railing. The bones of Keats and Raphael and St. Peter molder somewhere out there. The pope dreams a half mile away. Owen blinks up at me, mouth open, a crease in his forehead, as though his soul is still somewhere over the Atlantic, trying to catch up with the rest of him.

By the time the apartment is light again, none of us have slept. We need money, we need food. I reassemble our stroller and wrestle it down the stairwell. Shauna straps in the boys. Beyond the front gate the sidewalk stretches right and left. The sky is broken and humid; a little car rifles past and sets a plastic bag spinning in its wake.

“There’s more traffic to the left,” Shauna says.

“Is that good?”

“Maybe more traffic means more stores?”

I am resisting this logic when a neighbor appears behind us. Small, freckled, powerful-looking. She is American. Her name is Laura. Her husband is a fellow at the Academy in landscape architecture. She has just put her children on the bus for school and is now carrying out her recycling and going to buy ground beef.

She leads us left. Fifty feet up the sidewalk, four streets converge beneath a blocky stucco archway called the Porta San Pancrazio, a gate in Rome’s old defensive walls. There are no stoplights. Little cars push forward, each looking for a gap. A city bus heaves into the mix. Then a flatbed stacked with furniture. Then a pair of motor scooters. Everyone appears to be inching toward the same alley, where, as soon as they’re free of the logjam, the vehicles streak away, charging between lines of parked cars, their side mirrors either tucked in or torn off.

Laura chats all the way. As if today were just another day, as if our lives were not in peril, as if Rome were Cincinnati. Are there even crosswalks? Horns blare. A taxi nearly shaves off the stroller’s front wheels. “What airline did you guys fly?” Laura yells. Shauna says, “My goodness.” I feel like crouching in the gutter with my babies in my arms.

Another scooter (a motorino, Laura tells us) squeezes into the melee. The driver braces a four-foot banana plant in a pot on the little riding platform between his shoes. Its leaves flap against his shoulders as he passes.

Laura marches across the intersection, flings her recycling into a series of bins, points out storefronts farther down the street. She seems impossibly comfortable; she is an island of composure. I worry: Can we talk so loudly? In English?

The boys don’t make a sound. It’s hot. Apartment buildings loom above shops, hundreds of balconies crammed with geraniums, pygmy palms, tomatoes. Outside bars, teenagers drink coffee from glasses. Men in blue jumpsuits and combat boots stand in front of banks, handguns strapped to their hips. We pass a Fiat dealership in a storefront no bigger than the beauty salon next to it. We pass a pizzeria; an old man behind the glass counter plucks a flower off the end of a zucchini.

In the baby food section of a farmacia I hunt for anything recognizable and find labels illustrated with rabbits, sheep, and—worse—ponies.

“In Italy,” Laura says, “My Pretty Pony is a snack.”

She helps us find an ATM; she shows us where to buy disposable diapers. She sets us straight on the names of the neighborhoods: “Trastevere is behind us, down the stairs. The Janiculum, where we live, is just the name of the hill. Our neighborhood, the one we’re walking in, is called Monteverde.”

“Monteverde,” I say, practicing. Green hill. Before Laura leaves, she points us toward the vegetable market. “A presto,” she says, which leaves me reaching for my phrase book. Prestare? To give?

Then she’s gone. I think of Dante in Purgatory, turning to tell Virgil something, only to find Virgil is no longer there.

At the produce stand—we learn the hard way—you’re not supposed to touch the vegetables; you point at the insalatine or pomodori and the merchant will set them on the scale. The butcher’s eggs sit in open cartons, roasting in the sun. There are no tags on any of his meat; I gesture at something pink and boneless and cross my fingers.

The Kit Kats are packaged not in orange labels but in red. They taste better. So do the pears. We devour one and bleed pear juice all over the canopy of the stroller. The tomatoes—a dozen of them in a paper bag—appear to give off light.

The babies suck on biscuits. We glide through sun and shadow.

Two blocks from the market, on a street called Quattro Venti—the Four Winds—the smell of a bakery blows onto the sidewalk. I lock the stroller brake, pull open the door, and step into a throng. Everyone jostles everyone else; people who have just entered stoop and dive and squirm toward the counter. Should I be taking a number? Do I shout my order? I try to run through my Italian vocabulary: eight afternoons at a Berlitz in Boise, $400, and right now all I can remember is tazza da tè. Teacup.

A woman with whiskers is pressed against me, my chin in her hair. She smells like old milk. Loaves shuttle back and forth over my head. I know ciabatta. I know focaccia.

Behind the counter the only Italians I have seen wearing shorts slide about on the flour-slick tile in white sneakers. The crowd has driven me into a corner. Men who have just entered are getting their orders taken, passing bills forward.

Poppy seeds, sesame seeds, a crumpled wad of wax paper. I am a kernel beneath the millstone. Through the glass doors I can see Shauna crouched over the boys, who are screaming. Everything swims. What are the words? Scusi? Permesso? We can live without bread. All year if we have to. I lower my head and grapple my way out.

The bakery is not my only failure. In a hardware store I look around for key rings, but the owner stands in front of me with his hands clasped together, eager to help, and I don’t know how to say “key ring” or “I’m just looking,” so for a minute we face each other, wordless.

“Luce per notte,” I finally arrive at. “Per bambini.” And although I’m not there to buy children’s night-lights, he shows me one, so I buy it. The key rings wait until I can return with a dictionary.

According to a two-sentence project summary I had to send the Academy, I’ve come to Rome to continue writing my third book, a second novel, this one about the German occupation of a village in Normandy between 1940 and 1944. I have brought maybe fifty pages of prose, some photos of B-17s dropping firebombs, and a mess of scribbled notes.

My writing studio is in the palace next door to our apartment building: the American Academy itself, hushed, gigantic, imposing. While the babies nap, that first full afternoon in Rome, I pass through the big gate, wave to the gatekeeper in his little shed, and carry my notebooks up the front stairs. An arrow to the left points to “office”; an arrow to the right points to “library.” The courtyard is full of gravel and jasmine. A fountain trickles. I nod to a man in a black T-shirt with bloodshot eyes, his forearms smeared with oil paint.

Studio 235 is a rectangle with high ceilings called the Tom Andrews Studio, after a hemophilic poet who held the same fellowship I now have. He worked here in 2000; he died in 2002. His studio contains two desks, a little cot, and an office chair with the stuffing torn out of it.

Tom Andrews, I heard once, broke a world record by clapping his hands continuously for fourteen hours and thirty-one minutes. The first line of his second book is “May the Lord Jesus Christ bless the hemophiliac’s motorcycle.”

I talk to him as I slide furniture around.

“Tom,” I say, “I’ve been in Italy twenty hours and I’ve been asleep for one of them.”

“Tom,” I say, “I’m putting three books on your shelves.”

The window in the Tom Andrews Studio is six or seven feet high, and looks out at the three acres of trees and lawns behind the Academy. Bisecting the view, maybe twelve feet beyond the sill, is the trunk of a magnificent Italian pine.

All over the neighborhood I’ve noticed these trees: soaring, branchless trunks; high, subdividing crowns like the heads of neurons. In the months to come I will hear them called Italian pines, Roman pines, Mediterranean pines, stone pines, parasol pines, and umbrella pines—all the same thing: Pinus pinea. Regal trees, astounding trees, trees both unruly and composed at once, like princes who sleep stock-still but dream swarming dreams.

A half dozen umbrella pines stand behind the embassy across the street; a line of them thrust their heads over the 360-year-old wall that borders the Academy’s lawns. I never expected Rome to have trees like these, for a city of 3 million people to be a living garden, moss in the sidewalk cracks, streamers of ivy sashaying in archways, ancient walls wearing a haze of capers, thyme sprouting from church steeples. This morning the cobblestones were slick with algae. In the streets Laura escorted us through, clandestine stands of bamboo rustled in apartment courtyards; pines stood next to palms, cypress next to orange trees; I saw a thatch of mint growing from a sidewalk crack outside a video store.

Of the three books I’ve brought, one is about the Nazi occupation of France, because of the novel I’m trying to write. One is a selection of excerpts from Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, because the jacket copy says it offers a view of the natural world as it was understood in first-century Rome. The last is a field guide to trees. The tree book gives the umbrella pine a half of a page. The bark is gray-brown and fissured; the scales fall off from time to time, leaving light brown patches.2

A spreading walnut, a grove of olives; lindens, crab apples, a hedge made entirely of rosemary. The walls that hem in these gardens rise thirty feet in places, the stonework bleached by time, the upper reaches punctuated with crossbow loops, the ramparts bristling with weeds. Before electricity, before the umbrella pine out the window was even a pinecone, when the night sky above the Janiculum was as awash with stars as any sky anywhere, Galileo Galilei assembled his new telescope at a banquet in this very garden, just beneath my window, and showed guests the heavens.

Fifty yards away, in our apartment, Shauna grapples with the babies. I think of Owen’s swiveling head, Henry’s circular eyes. “They are miracles,” I tell the ghost of Tom Andrews. Born from cells smaller than the period at the end of this sentence—much smaller than that period—the boys are suddenly big and loud and soak the fronts of their shirts with drool.

I open a notebook to an empty page. I try to put down a few sentences about gratitude, about wonder.

We fry pork chops in a dented skillet, drink wine from water glasses. Chimney swifts race across the terrace. All night the boys wake and cry in their strange cribs. I feed Henry at 12:40 a.m. (the microwave clock reads 0:40) and swaddle him and finally convince him to fall asleep. Then I lie down on the sofa with my head on a stack of diapers and two spit-up cloths stretched over my body like napkins; our only blanket is on the bed, on top of Shauna. Ten minutes. Twenty minutes. Why even bother? It’s only a dream before Owen will wake.

What did Columbus write in his log as he set out from Spain? “Above all, it is fitting that I forget about sleeping and devote much attention to navigation in order to accomplish this.”3

Henry wakes again at two. Owen is up at three. Each time, rising out of a half sleep, it takes a full minute to remember what I have forgotten: I am a father; we have moved to Italy.

All night I carry one crying baby or the other onto the terrace. The air is warm and sweet. Stars burn here and there. In the distance little strands of glitter climb the hills.

“Molto, molto bella,” our taxi driver, Roberto, told us as he drove us, our seven duffel bags, and our forty-five-pound stroller here from the airport. He had a scrubby chin and two cell phones and cringed whenever the babies made a noise.

“Non c’è una città più bella di Roma,” he said. There is no city more beautiful than Rome.

On our second morning in Italy we push the stroller out the front gate and turn right. The boys moan; the axles rattle. Little cars shoot past. We round a corner and a chain-link fence gives way to hedges, which give way to the side of a monumental marble-and-granite fountain. We wheel gape-jawed around to its front.

Five niches in a six-columned headboard as big as a house unload water into a shallow, semicircular pool. Seven lines of Latin swarm across its face; griffins and eagles ride its capitals. The Romans, we’ll learn later, call it simply il Fontanone. The big fountain. It was completed in 1690; it had taken seventy-eight years to build. The travertine seems almost to glow; it is as if lights have been implanted inside the stone.

Across the street is another marvel: a railing, some benches, and a perch with a view over the entire city. We dodge traffic, roll the boys to the parapet. Here is all of Rome: ten thousand rooftops, church domes, bell towers, palaces, apartments; an airplane traversing slowly from right to left; the city extending back across the plain. Strings of distant towns marble hills at the horizon. Beneath us, for as far as we can see, drifts a bluish haze—it is as if the city were submerged beneath a lake, and a wind were ruffling its surface.

Darmowy fragment się skończył.