Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «I Know Who You Are»

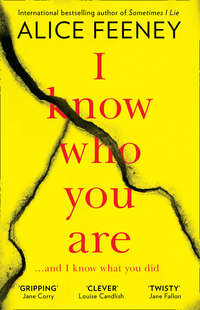

ALICE FEENEY is a writer and journalist. She spent fifteen years at the BBC where she worked as a reporter, news editor, arts and entertainment producer and One O’clock news producer.

Alice has lived in London and Sydney and has now settled in the Surrey countryside, where she lives with her husband and dog.

Her debut novel, Sometimes I Lie, was a New York Times and international bestseller. The book has been sold in over twenty countries and is being made into a TV series by a major film studio. I Know Who You Are is her second novel.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Diggi Books Ltd

Alice Feeney asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008236083

More praise for Alice Feeney:

‘Boldly plotted, tightly knotted – a provocative true-or-false thriller that deepens and darkens to its ink-black finale. Marvellous.’

A J Finn

‘A bold and original voice – I loved this book.’

Clare Mackintosh

‘Expect perfectly imbedded twists and sharply drawn characters. A brilliant thriller.’

Ali Land

‘A gripping debut with a brilliant twist, I loved it.’

B A Paris

‘A tightly written thriller with an ending that demands you go straight back to the beginning.’

Metro

‘Satisfyingly serpentine, and with a terrific double twist in the tale, it leaves you longing for more.’

Daily Mail

‘Intriguing, original and addictive, I can’t wait to see what the author does after this blinding debut.’

The Sun

‘Clever, compelling and masterfully plotted.’

Daily Express

‘Sometimes I Lie is a rare book, combining helter skelter twists with razor sharp sentences. Make sure you read it in a well lit room, Alice Feeney’s imagination is a very dark place indeed.’

Dan Dalton, BuzzFeed

‘This is a thriller that grabs you and holds you in its thrall.’

Nicholas Searle

For Jonny.

Agents come in all shapes and sizes.

I got the best.

Not everybody wants to be somebody.

Some people just want to be somebody else.

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Forty-Nine

Fifty

Fifty-One

Fifty-Two

Fifty-Three

Fifty-Four

Fifty-Five

Fifty-Six

Fifty-Seven

Fifty-Eight

Fifty-Nine

Sixty

Sixty-One

Sixty-Two

Sixty-Three

Sixty-Four

Sixty-Five

Sixty-Six

Sixty-Seven

Sixty-Eight

Sixty-Nine

Seventy

Seventy-One

Seventy-Two

Seventy-Three

Seventy-Four

Six Months Later . . .

Acknowledgements

Reading group questions

Keep Reading...

About the Publisher

One

London, 2017

I’m that girl you think you know, but you can’t remember where from.

Lying is what I do for a living. It’s what I’m best at: becoming somebody else. The eyes are the only part of me I still recognise in the mirror, staring out beneath the made-up face of a made-up person. Another character, another story, another lie. I look away, ready to leave her behind for the night, stopping briefly to stare at what is written on the dressing-room door:

AIMEE SINCLAIR

My name, not his. I never changed it.

Perhaps because, deep down, I always knew that our marriage would only last until life did us part. I remind myself that my name only defines me if I allow it to. It is merely a collection of letters, arranged in a certain order; little more than a parent’s wish, a label, a lie. Sometimes I long to rearrange those letters into something else. Someone else. A new name for a new me. The me I became when nobody else was looking.

Knowing a person’s name is not the same as knowing a person.

I think we broke us last night.

Sometimes it’s the people who love us the most that hurt us the hardest, because they can.

He hurt me.

We’ve made a bad habit of hurting each other; things have to be broken in order to fix them.

I hurt him back.

I check that I’ve remembered to put my latest book in my bag, the way other people check for a purse or keys. Time is precious, never spare, and I kill mine by reading on set between filming. Ever since I was a child, I have preferred to inhabit the fictional lives of others, hiding in stories that have happier endings than my own; we are what we read. When I’m sure I haven’t forgotten anything, I walk away, back to who and what and where I came from.

Something very bad happened last night.

I’ve tried so hard to pretend that it didn’t, struggled to rearrange the memories, but I can still hear his hate-filled words, still feel his hands around my neck, and still see the expression I’ve never seen his face wear before.

I can still fix this. I can fix us.

The lies we tell ourselves are always the most dangerous.

It was a fight, that’s all. Everybody who has ever loved has also fought.

I walk down the familiar corridors of Pinewood Studios, leaving my dressing room, but not my thoughts or fears too far behind. My steps seem slow and uncertain, as though they are deliberately delaying the act of going home; afraid of what will be waiting there.

I did love him, I still do.

I think it’s important to remember that. We weren’t always the version of us that we became. Life remodels relationships like the sea reshapes the sand; eroding dunes of love, building banks of hate. Last night, I told him it was over. I told him I wanted a divorce and I told him that I meant it this time.

I didn’t. Mean it.

I climb into my Range Rover and drive towards the iconic studio gates, steering towards the inevitable. I fold in on myself a little, hiding the corners of me I’d rather others didn’t see, bending my sharp edges out of view. The man in the booth at the exit waves, his face dressed in kindness. I force my face to smile back, before pulling away.

For me, acting has never been about attracting attention or wanting to be seen. I do what I do because I don’t know how to do anything else, and because it’s the only thing that makes me feel happy. The shy actress is an oxymoron in most people’s dictionaries, but that is who and what I am. Not everybody wants to be somebody. Some people just want to be somebody else. Acting is easy, it’s being me that I find difficult. I throw up before almost every interview and event. I get physically ill and am crippled with nerves when I have to meet people as myself. But when I step out onto a stage, or in front of a camera as somebody different, it feels like I can fly.

Nobody understands who I really am, except him.

My husband fell in love with the version of me I was before. My success is relatively recent, and my dreams coming true signalled the start of his nightmares. He tried to be supportive at first, but I was never something he wanted to share. That said, each time my anxiety tore me apart, he stitched me back together again. Which was kind, if also self-serving. In order to get satisfaction from fixing something, you either have to leave it broken for a while first, or break it again yourself.

I drive slowly along the fast London streets, silently rehearsing for real life, catching unwelcome glimpses of my made-up self in the mirror. The thirty-six-year-old woman I see looks angry about being forced to wear a disguise. I am not beautiful, but I’m told I have an interesting face. My eyes are too big for the rest of my features, as though all the things they have seen made them swell out of proportion. My long dark hair has been straightened by expert fingers, not my own, and I’m thin now, because the part I’m playing requires me to be so, and because I frequently forget to eat. I forget to eat because a journalist once called me ‘plump but pretty.’ I can’t remember what she said about my performance.

It was a review of my first film role last year. A part that changed my life, and my husband’s, for ever. It certainly changed our bank balance, but our love was already overdrawn. He resented my newfound success – it took me away from him – and I think he needed to make me feel small in order to make himself feel big again. I’m not who he married. I’m more than her now, and I think he wanted less. He’s a journalist, successful in his own right, but it’s not the same. He thought he was losing me, so he started to hold on too tight, so tight that it hurt.

I think part of me liked it.

I park on the street and allow my feet to lead me up the garden path. I bought the Notting Hill town house because I thought it might fix us while we continued to remortgage our marriage. But money is a band-aid, not a cure for broken hearts and promises. I’ve never felt so trapped by my own wrong turns. I built my prison in the way that people often do, with solid walls made from bricks of guilt and obligation. Walls that seemed to have no doors, but the way out was always there. I just couldn’t see it.

I let myself in, turning on the lights in each of the cold, dark, vacant rooms.

‘Ben,’ I call, taking off my coat.

Even the sound of my voice calling his name sounds wrong, fake, foreign.

‘I’m home,’ I say to another empty space. It feels like a lie to describe this as my home; it has never felt like one. A bird never chooses its own cage.

When I can’t find my husband downstairs, I head up to our bedroom, every step heavy with dread and doubt. The memories of the night before are a little too loud now that I’m back on the set of our lives. I call his name again, but he still doesn’t reply. When I’ve checked every room, I return to the kitchen, noticing the elaborate bouquet of flowers on the table for the first time. I read the small card attached to them; there’s just one word:

Sorry.

Sorry is easier to say than it is to feel. Even easier to write.

I want to rub out what happened to us and go back to the beginning. I want to forget what he did to me and what he made me do. I want to start again, but time is something we ran out of long before we started running from each other. Perhaps if he’d let me have the children I so badly wanted to love, things might have been different.

I retrace my steps back to the lounge and stare at Ben’s things on the coffee table: his wallet, keys and phone. He never goes anywhere without his phone. I pick it up, carefully, as though it might either explode or disintegrate in my fingers. The screen comes to life and reveals a missed call from a number I don’t recognise. I want to see more, but when I press the button again the phone demands Ben’s passcode. I try and fail to guess several times, until it locks me out completely.

I search the house again, but he isn’t here. He isn’t hiding. This isn’t a game.

Back out in the hall, I notice that the coat he always wears is where he left it, and his shoes are still by the front door. I call his name one last time, so loud that the neighbours on the other side of the wall must hear me, but there’s still no answer. Maybe he just popped out.

Without his wallet, phone, keys, coat or shoes?

Denial is the most destructive form of self-harm.

A series of words whisper themselves repeatedly inside my ears:

Vanished. Fled. Departed. Left. Missing. Disappeared.

Then the carousel of words stops spinning, finally settling on the one that fits best. Short and simple, it slots into place, like a piece of a puzzle I didn’t know I’d have to solve.

My husband is gone.

Two

I wonder where other people go when they turn off the lights at night.

Do they all drift and dream? Or are there some, like me, who wander somewhere dark and cold within themselves, digging around inside the shadows of their blackest thoughts and fears, clawing away at the dirt of memories they wish they could forget? Hoping nobody else can see the place they have sunk down into?

When the race to sleep is beaten by the sound of my alarm, I get up, get washed, get dressed. I do all the things that I would normally do, if this were a normal day. I just can’t seem to do them at a normal speed. Every action, every thought, is painfully slow. As though the night were deliberately holding me back from the day to come.

I called the police before I went to bed.

I wasn’t sure whether it was the right thing to do, but apparently, there is no longer any need to wait twenty-four hours before notifying the police when someone disappears. The word makes it sound like a magic trick, a disappearing act, but I’m the actress, not my husband. The voice of the stranger on the phone was reassuring, even though the words it delivered weren’t. One word in particular, which he repeatedly hissed into my ear: missing.

Missing person. Missing husband. Missing memories.

I can remember the exact expression my husband wore the last time I saw his face, but what happened next is a blur at best. Not because I am forgetful, or a drunk – I am neither of those things – but because of what happened afterwards. I close my eyes, but I can still see him, his features twisted with hate. I blink the image away as though it were a piece of grit, a minor irritant, obstructing the view of us I prefer.

What have we done? What did I do? Why did he make me?

The kind policeman I eventually spoke to, once I’d managed to dial the third and final number, took our details and said that someone would be in touch. Then he told me not to worry.

He may as well have told me not to breathe.

I don’t know what happens next and I don’t like it. I’ve never been a fan of improvisation, I prefer my life to be scripted, planned and neatly plotted. Even now, I keep expecting Ben to walk through the door, deliver one of his funny and charming stories to explain it all away, kiss us better. But he doesn’t do that. He doesn’t do anything. He’s gone.

I wish there were someone else I could call, tell, talk to, but there isn’t.

My husband gradually reorganised my life when we first met, criticising my friends and obliterating my trust in all of them, until we were all we had left. He became my moon, constantly circling, controlling my tides of self-doubt, occasionally blocking out the sun altogether, leaving me somewhere dark, where I was afraid and couldn’t see what was really going on.

Or pretended not to.

The ties of a love like ours twist themselves into a complicated knot, one that is hard to unravel. People would ask why I stayed with him if they knew the truth, and I’d tell them the truth if they did: because I love us more than I hate him, and because he’s the only man I’ve ever pictured myself having a child with. Despite everything he did to hurt me, that was still all I wanted: for us to have a baby and a chance to start again.

A brand-new version of us.

Refusing to let me become a mother was cruel. Thinking I’d just accept his choices as my own was foolish. But I’m good at pretending. I’ve made a living out of it. Papering over the cracks doesn’t mean they’re not there, but life is prettier when you do.

I don’t know what to do now.

I’m trying to carry on like normal, but struggling to remember what that is.

I’ve been running nearly every day for almost ten years, it is something I file away in the slim folder of things I think I am good at, and I enjoy it. I run the same route every single morning, a strict creature of habit. I make myself put on my trainers, shaky fingers struggling to remember how to tie laces they’ve tied a thousand times before. Then I tell myself that staring at the bare walls isn’t going to help anyone or bring him back.

My feet find their familiar rhythm: fast but steady, and I listen to music to disguise the soundtrack of the city. The adrenaline rush kicks in to dismantle the pain, and I push myself a little harder. I run past the pub on the corner where Ben and I used to go drinking on Friday nights, before we forgot who and how to be with each other. Then I run past the council tower blocks and the millionaires’ playground of terraced luxury on the neighbouring street; the haves and have-nots side by side, at least in proximity.

Moving to an expensive corner of West London was Ben’s idea. I was away in LA when we bought the place; fear persuaded me it was the right thing to do. I didn’t even step inside before we owned it. When I finally did, the whole house was quite transformed from the photos I had seen online. Ben renovated our new home all by himself: new fixtures and fittings for the brand-new us we thought we could and should be.

As I run around the corner of the street, my eyes find the bookshop. I try not to look, but it’s like the scene of an accident and I can’t help it. It’s where we arranged to meet for our first date. He knew about my love of books, which is why he chose this place. I arrived a little early that night, filled with anticipation and nerves, and browsed the shelves while I waited. Fifteen minutes later, when my date still hadn’t turned up, my anxiety levels were peaking.

‘Excuse me, are you Aimee?’ asked an elderly gentleman with a kind smile.

I felt confused, a little sick; he was nothing like the handsome young man in the profile picture I had seen. I considered fleeing from the shop.

‘Another customer came in earlier; he bought this and asked me to give it to you. He said it was a clue.’ The man beamed as though this were the most fun he’d had in years. Then he held out a neatly wrapped brown-paper parcel. With the tension removed from the situation, things seemed to fall into place and I realised this was the owner of the shop, not my date. I thanked him and took what I guessed was a book, grateful when he left me alone to unwrap it. Inside, I found one of my childhood favourites: The Secret Garden. It took a while for the penny to drop, but then I remembered that the florist on the corner shared the same name as the book.

The woman in the flower shop grinned as soon as I walked in, my entrance accompanied by the tinkle of a bell on her door.

‘Aimee?’

When I nodded, she presented me with a bouquet of white roses. There was a note:

Roses are white.

So sorry I’m late.

Can’t wait for tonight.

You’re my perfect date.

I read it three times, as though trying to translate the words, then noticed the florist still smiling in my direction. People staring at me has always made me feel uncomfortable.

‘He said he’d meet you at your favourite restaurant.’

I thanked her and left. We didn’t have a favourite restaurant, having never eaten out together, so I walked along the high street carrying my book and flowers, enjoying the game. I replayed our email conversations in my mind and remembered one about food. His preferences had all been so fancy, mine . . . less so. I had regretted telling him my favourite meal and blamed my upbringing.

The man behind the counter at the fish-and-chips shop smiled. I was a regular back then.

‘Salt and vinegar?’

‘Yes please.’

He shovelled some chips into a paper cone, then gave them to me, along with a ticket for a film screening later that night. The chips were too hot, and I was too anxious to eat them as I hurried along the road. But as soon as I saw Ben standing outside the cinema, all my fear seemed to disappear.

I remember our first kiss.

It felt so right. We had a connection I could neither fathom or explain, and we slotted together as though we were meant to be that way. I smile at the memory of who we were then. That version of us was good. Then I stumble on the uneven pavement outside the cinema, and it brings me back to the present. Its doors are closed. The lights are off. And Ben is gone.

I run a little faster.

I pass the charity shops, wondering if the clothes in the windows were donated in generosity or sorrow. I run past the man pushing a broom along the pavement, sweeping away the litter of other people’s lives. Then I run past the Italian restaurant where the waitress recognised me the last time we ate there. I haven’t been back since; it feels as if I can’t.

I am paralysed with a unique form of fear when strangers recognise me. I just smile, try to say something friendly, then retreat as fast as I can. Thankfully it doesn’t happen too often. I’m not A-list. Not yet. Somewhere between a B and C I suppose, a bit like my bra size. The version of myself I wear in public is far more attractive than the real me. It’s been carefully tailored, a cut above my standard self; she’s someone nobody should see.

I wonder when his love for me ran out?

I take a shortcut through the cemetery and the sight of a child’s grave fills me with grief, redirecting my mind from thoughts of who we were, to who we might have been, had life unfolded differently. I try to hold on to the happy memories, pretend that there were more than there were. We are all programmed to rewrite our past to protect ourselves in the present.

What am I doing?

My husband is missing. I should be at home, crying, calling hospitals, doing something. The memory interrupts my thoughts but not my footsteps, and I carry on. I only stop when I reach the coffee shop, exhausted by my own bad habits: insomnia and running away from my problems.

It’s already busy, filled with overworked and underpaid Londoners needing their morning fix, sleep and discontentment still in their eyes. When I reach the front of the queue, I ask for my normal latte and make my way to the till. I use contactless to pay, and disappear inside myself again until the unsmiling cashier speaks in my direction. Her blonde hair hangs in uneven plaits on either side of her long face, and she wears a frown like a tattoo.

‘Your card has been declined.’

I don’t respond.

She looks at me as though I might be dangerously stupid. ‘Do you have another card?’ Her words are deliberately slow and delivered with increased volume, as though the situation has already exhausted her of all patience and kindness. I feel other sets of eyes in the shop joining hers, all converging on me.

‘It’s two pounds forty. It must be your machine, please try it again.’ I’m appalled by the pathetic sound impersonating my voice coming from my mouth.

She sighs, as though she is doing me an enormous favour, and making a huge personal sacrifice, before stabbing the till with her nail-bitten finger.

I hold out my bank card, fully aware that my hand is trembling and that everyone can see.

She tuts, shakes her head. ‘Card declined. Have you got any other way of paying, or not?’

Not.

I take a step back from my untouched coffee, then turn and walk out of the shop without another word, feeling their eyes follow me, their judgment not far behind.

Ignorance isn’t bliss, it’s fear postponed to a later date.

I stop outside the bank and allow the cash machine to swallow my card, before entering my pin and requesting a small amount of money. I read the unfamiliar and unexpected words on the screen twice:

SORRY

INSUFFICIENT FUNDS AVAILABLE

The machine spits my card back out in electronic disgust.

Sometimes we pretend not to understand things that we do.

I do what I do best instead: I run. All the way back to the house that was never a home.

As soon as I’m inside, I pull out my phone and dial the number on the back of my bank card, as though this conversation could only be had behind closed doors. Fear, not fatigue, withholds my breath, so that it escapes my mouth in a series of spontaneous bursts, disfiguring my voice. Getting through the security questions is painful, but eventually the woman in a distant call centre asks the question I’ve been waiting to hear.

‘Good morning, Mrs Sinclair. You have now cleared security. How can I help you?’

Finally.

I listen while a stranger calmly tells me that my bank account was emptied, then closed yesterday. Over ten thousand pounds had been sitting in it – the account I reluctantly agreed to make in joint names, when Ben accused me of not trusting him. Turns out I might have been right not to. Luckily, I’ve squirrelled most of my earnings away in accounts he can’t access.

I stare down at Ben’s belongings still sitting on the coffee table, then cradle my phone between my ear and shoulder to free up my hands. It feels a little intrusive to go through his wallet – I’m not that kind of wife – but I pick it up anyway. I peer inside, as though the missing ten thousand pounds might be hidden between the leather folds. It isn’t. All I find is a crumpled-looking fiver, a couple of credit cards I didn’t know he had, and two neatly folded receipts. The first is from the restaurant we ate at the last time I saw him, the second is from the petrol station. Nothing unusual about that. I walk to the window and peel back the edge of the curtain, just enough to see Ben’s car parked in its usual spot. I let the curtain fall, and put the wallet back on the table, exactly how I found it. A marriage starved of affection leaves an emaciated love behind; one that is frail, easy to bend and break. But if he was going to leave me and steal my money, then why didn’t he take his things with him too? Everything he owns is still here.

It doesn’t make any sense.

‘Mrs Sinclair, is there anything else I can help you with today?’ The voice on the phone interrupts my confused thoughts.

‘No. Actually, yes. I just wondered if you could tell me what time my husband closed our joint account?’

‘The final withdrawal was made in branch at seventeen twenty-three.’ I try to remember yesterday – it seems so long ago. I’m fairly sure I was home from filming by five at the latest, so I would have been here when he did it. ‘That’s strange . . . ’ she says.

‘What is?’

She hesitates before answering.

‘Your husband didn’t withdraw the money or close the account.’

She has my full attention now.

‘Then who did?’

There is another long pause.

‘Well, according to our records, Mrs Sinclair, it was you.’