Książki nie można pobrać jako pliku, ale można ją czytać w naszej aplikacji lub online na stronie.

Czytaj książkę: «Chasing the Moon: The Story of the Space Race - from Arthur C. Clarke to the Apollo landings»

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

First published in the United States by Ballentine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC, New York

Copyright © Alan Andres and Robert Stone

Insert photos courtesy of NASA unless otherwise indicated

“AMERICAN EXPERIENCE”™ is a trademark of the WGBH Educational Foundation.

Used with permission

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Tom Lehrer for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Wernher von Braun” by Tom Lehrer, copyright © 1965 by Tom Lehrer. Reprinted by permission of the author

Alan Andres and Robert Stone assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

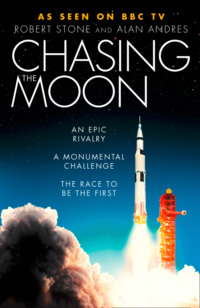

Cover image © Getty Images

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008307875

eBook Edition © June 2019 ISBN: 9780008307851

Version: 2019-05-30

For my mother, who awakened her ten-year-old son in the middle of an English midsummer night to watch Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin make history as they walked on the Moon.

—R.S.

For Charlie, older brother and teenage rocket scientist, who, as the youngest accredited journalist covering the launch of Apollo 14, backpacked and hitchhiked 1200 miles to Cape Kennedy.

— A.A.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

PROLOGUE JULY 16, 1969

CHAPTER ONE A PLACE BEYOND THE SKY (1903–1950)

CHAPTER TWO THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON (1952–1960)

CHAPTER THREE THE NEW FRONTIER (1961–1963)

CHAPTER FOUR WELCOME TO THE SPACE AGE (1964–1966)

CHAPTER FIVE EARTHRISE (1967–1968)

CHAPTER SIX MAGNIFICENT DESOLATION (1969)

CHAPTER SEVEN THE FINAL FRONTIER (1970–1979)

APPENDIX AFTER A FEW MORE REVOLUTIONS AROUND THE SUN

PICTURE SECTION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABOUT THE TYPE

ABOUT THE BOOK

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

JULY 16, 1969

THE SUN BEGAN rising over the northeast coast of Florida on what would be a humid subtropical mid-July morning. The brown pelicans swooping over the dunes sensed the day was anything but typical. Parked tightly together on the sides of the narrow roads to the beaches and causeways were thousands of cars and campers. The air carried the thrumming sound of helicopters ferrying visitors to the Kennedy Space Center. Since shortly after sunrise, all the roads to the Cape had become clogged with traffic.

Nearly a million people were gathering under the harsh Florida sun to witness the departure of the first humans to attempt a landing on another world, the Earth’s moon, 239,000 miles away. Should it be successful, the piloted lunar landing would culminate a decade of mounting anticipation.

Eight years earlier, President John Kennedy stood before Congress and called for the United States to put a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth before the end of the decade. At the time, the Soviet Union’s commanding position in space appeared assured. They had been the first to launch an artificial satellite, the first to fly past the Moon, and, in a one-hundred-eight-minute flight, the first to orbit a human around the Earth. When Kennedy addressed Congress, the suborbital flight of the only American to venture into space had been less than fifteen minutes.

But by July 1969, as America readied to launch Apollo 11 from the space center bearing the name of the late president, the Soviet space threat had receded. This would be the twenty-first piloted NASA space mission; in comparison, the Russian total was twelve, and all had remained in low earth orbit. Now the richest nation on Earth was about to undertake a daring technological feat of unprecedented magnitude, a demonstration of national will framed as a world media event. It was a story of courage, adventure, and scientific exploration as well as an exercise in geopolitics.

If not for the persuasive influence of a select group of visionaries, this moment in history would have been inconceivable. For some it was the fulfillment of a personal dream dating back to childhood. For others it was a way to promote democracy, extend human knowledge, and establish the nation’s technological and academic preeminence. Some saw it as humanity’s inevitable evolutionary destiny; others their personal patriotic duty.

A few hundred feet south of the giant Vehicle Assembly Building, where the Saturn V moon rocket had been put together, a balding middle-aged Englishman dressed in a gray suit looked toward the launchpad from CBS News’s temporary broadcast facility. Arthur C. Clarke had imagined this day since his teenage years, having co-authored one of the first serious publications about a possible expedition to the Moon. He was scheduled to appear on live television with CBS’s veteran newsman Walter Cronkite shortly after Apollo 11’s liftoff. During the preceding year, Clarke’s reputation as a leading author of science fiction had risen to greater prominence due to his association as co-writer of director Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the top-grossing film of 1968. For Clarke, the moon landing would establish the extraterrestrial presence of Homo sapiens in the cosmos, with a promise of what the human race might achieve in the future.

At the same moment, in NASA’s Launch Control Center, a few hundred feet away from the press center, Wernher von Braun also looked toward the launchpad, three and a half miles away. One of the most famous men in America, the tall, handsome German-born rocket engineer trained his field glasses on the 365-foot-tall Saturn V. Designed by a team under his direction, it was the most powerful rocket in the world. Much like his friend Arthur Clarke, von Braun had his fascination with space travel ignited at an early age by reading science fiction.

A decade earlier the German had been hailed a national hero following the successful launch of the United States’s first satellite. A master salesman, von Braun had a unique skill, persuading powerful decision makers—senators, presidents, generals, and dictators—to give him whatever he needed to build his powerful rockets to explore space. However, despite his renown and having lived in the United States for nearly a quarter century, questions surrounding von Braun’s past continued to shadow him. During World War II, he had overseen the creation of the first long-range guided ballistic missile for Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. This portion of his biography was well known and had even served as the basis for a Hollywood feature film, but despite having addressed it repeatedly in the past, von Braun and his wartime career in particular remained controversial and open to occasional speculation.

Adjacent to both the designated press area and the Launch Control Center were a few simple wooden bleachers, not unlike those found alongside a typical high school football field. This was NASA’s VIP viewing area, the most coveted location on Cape Kennedy, despite its lack of shade on this sweltering July morning. Ambassadors, senators, congressmen, corporate heads, authors, and celebrities had begun assembling there less than an hour before Apollo 11’s scheduled liftoff time at 9:32 A.M.

Press photographers had trained their lenses on comedian Jack Benny and the popular host of The Tonight Show, Johnny Carson, when their attention was diverted by the arrival of former president Lyndon Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird. This was a rare public appearance for Johnson, one of his first since departing the White House six months earlier. Though the name of President Kennedy would always be linked to the national initiative to place a man on the Moon, Johnson’s role as chairman of the National Space Council while vice president and later during his presidency was nearly as decisive.

Johnson climbed the bleachers, stopping to greet old Washington colleagues. Near the top of the stand was Army chief of staff General William Westmoreland, until recently commander of the half million American troops in Vietnam. Directly behind President Johnson and Lady Bird was seated a man far less recognizable to the general public but the one person the former president had relied upon to make this day a reality. Unlike the astronauts or von Braun, former NASA administrator James Webb had never appeared on the cover of a national magazine or been given extensive television exposure. But Webb had been the unwavering choice of both presidents Kennedy and Johnson as the best person to run the American space program during its most challenging and transformative years.

When Americans heard Kennedy’s 1961 proposal for a hugely ambitious lunar program, they were uncertain precisely how NASA might accomplish this task and what its final expense might be. The rockets, the spacecraft, and much of the supporting technology to achieve this goal on schedule had to be invented and refined before the end of the decade. No less a space visionary than Clarke and von Braun, James Webb combined insight from his experience running a major federal government agency with years of management experience as a corporate executive. Under his leadership through most of the 1960s, NASA had accomplished a series of spectacular space milestones and had overcome a devastating tragedy that had threatened to end the moon program, only to arrive at this day.

Nearly seven thousand names appeared on NASA’s official VIP list; however, far fewer were present in the viewing stands. Notably absent were two prominent Washington politicians. President Kennedy’s only surviving brother, Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, had chosen to view the launch from the congressional offices in Washington. President Richard Nixon was also in Washington, watching the event on television at the White House with Frank Borman, the astronaut who months earlier had commanded the riskiest space mission ever attempted, the first human voyage to the Moon. Nixon had wanted to dine with the astronauts at the Cape the evening before the launch, but the plan had been canceled by the flight surgeon, ostensibly to limit the astronauts’ exposure to germs prior to their departure.

At Cape Kennedy and around the world, as the countdown clock reached zero, time seemed to stand still. Millions watching the live television broadcast held their breath and trained their eyes on the picture coming from Pad 39A. Held down by four massive arms at the base of the pad, the Saturn V trembled as its massive engines began to fire, soon building to a combined force of 7.6 million pounds of thrust, at which point the quartet of restraining mechanisms released their grip simultaneously. Three and a half miles away, those assembled began to hear the delayed rumble of the engines as they increased in volume and to feel a steadily building vibration through the soles of their feet.

Slowly lifted on a blinding pillar of fire, the Saturn V began to ascend heavenward as it fought to escape the gravitational confines of the Earth. The people watching carried within their genetic code an inherited biological disposition to dream of a better future and persevere against difficulties and constraints that could seem as daunting as the natural forces pulling against the combined power of the Saturn’s engines. The hope and aspirations of countless previous generations had powered the human chronicle to reach this moment invested with so much promise.

CHAPTER ONE

A PLACE BEYOND THE SKY

(1903–1950)

THE BOOK IN the shop window caught the boy’s attention immediately. The vibrant purple dust jacket depicted a bullet-shaped machine trailed by an arc of orange flame. If there was any doubt in Archie Clarke’s mind what the illustration was intended to depict, the book’s title, The Conquest of Space, made it obvious. It was a spaceship. The captivating image reminded him of the colorful covers of the American science-fiction magazines that he had seen in the back room of Woolworth’s.

Spectacled fourteen-year-old Archie peered into the small W. H. Smith bookshop located a short distance from his grandmother’s house on England’s Bristol Channel. Dressed in short pants and an Oxford shirt, Archie was walking with his aunt Nellie toward Minehead’s main shopping arcade. It was 1932, and Archie had recently lost his father, after a long illness exacerbated by injuries sustained during a German poison-gas attack in World War I. He routinely visited his grandmother and aunt in the small but active southwest England beach resort during the weekends and holidays, leaving his mother freer to attend to his younger siblings on the remote family farm a few miles away.

Nellie Willis, a tall young woman with an intelligent face framed by a brown bob, doted on her clever nephew. She could see that the book displayed in the shop window fascinated him. Despite the family’s struggling finances, she gave Archie the “six and seven”—six shillings and seven pence—to purchase it and bring it home.

But when Archie opened the book, he discovered it wasn’t the adventure story that he had expected. Instead, he was looking at a book detailing the fundamentals of rocket science—astronautics—supplemented with an imagined account of the first journey to the Moon. Until this moment Archie had assumed space travel was a fantasy. Now he learned that it was actually possible for humans to leave their planet and explore space and that it could happen in the not-too-distant future.

Decades later, as one of the world’s leading masters of science fiction and the co-author of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C. Clarke would point to that day in 1932 as the moment his life changed. His imagination had been energized by a book, prompting him to wonder about what it might be like when humans began to explore space. In the early 1930s, few in government, media, or business regarded human space travel as a serious possibility. But in Archie Clarke’s mind it held transformative and liberating options. If the human species could escape the confines of gravity, was it conceivable that other fantastic possibilities might come to pass in the near future as well?

Archie’s fascination with the promise of space travel would motivate and determine the direction of his life following that chance encounter with The Conquest of Space. He joined a small cadre of visionaries, theorists, and space-travel advocates whose youthful dreams, curiosity, and determination led directly to humanity’s first steps on an alien world only three decades later.

The theoretical mathematics upon which all rocket science was based had begun to circulate in prominent scientific journals only a decade before the publication of The Conquest of Space. In the early twentieth century, three independent-minded theorists, intrigued by the idea of space travel after reading works of science fiction as adolescents, attempted to solve the theoretical physics necessary to carry out an actual escape from Earth’s gravity. Working autonomously, Russia’s Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, American professor Robert Goddard, and physicist Hermann Oberth in Germany conducted their research and study in each of the three countries that would later witness the most decisive events of the early space age. All three theorists were social outsiders intrigued by utopian ideals, and each harbored a personal belief that space travel would inevitably transform human destiny.

The first stirrings of the modern space age arose not in a wealthy industrial nation but in agrarian czarist Russia. At the turn of the century, a popular spiritual philosophy called cosmism—a mixture of elements from Eastern and Western thought, animism, theosophy, and mystical aspects of the Russian Orthodox Church—had influenced a new generation of writers, scientists, and intellectuals. For Russian cosmists, space travel would be the ultimate liberation; once the shackles of the Earth’s gravity had been removed and humans inhabited space, the souls of the dead would be resurrected and all humanity would partake in cosmic immortality.

The founding philosopher of Russian cosmism, Nikolai Fedorov, a noted librarian and scholar, chose to personally tutor a bright but impoverished teenager who had been prohibited from attending school due to severe deafness. The student, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, had an eccentric and strikingly independent intellect and within a few years was hired as a small-town schoolmaster, despite his disability. In his spare time, Tsiolkovsky conducted independent research on many scientific subjects, including space travel. He had read Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon during his adolescence, and later he even tried his hand at writing his own fictional scientific romances.

© NASA

Russia’s Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a rural Russian schoolteacher whose 1905 paper first introduced the mathematical equation on which all rocket science is founded. A utopian, Tsiolkovsky believed that human space flight would lead to universal happiness. In a letter he wrote, “Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot live in a cradle forever.”

In 1903 Tsiolkovsky published a scientific paper that contained the first appearance of what came to be known as the “rocket equation,” a mathematical formula comparing a rocket’s mass ratio to its velocity, the essential calculation necessary to determine how to escape a planet’s gravity. Unfortunately, the importance of his publication went unnoticed; the Russian scientific community ignored his work, dismissing it as the musings of an amateur. His paper would remain unread for another twenty years. Undaunted, Tsiolkovsky continued his studies, going on to publish nearly four hundred scientific papers on such matters as space-vehicle weightlessness, the operation of multi-staged launch vehicles, the orbital dynamics of differing rocket burns, and the scientific advantages of polar orbits.

A full decade after Tsiolkovsky’s groundbreaking paper, in 1913, a French aircraft designer named Robert Esnault-Pelterie independently published his own version of the rocket equation. But once again few took notice. In the United States, Robert Goddard, the second of the three pioneers of rocketry and a part-time instructor and research fellow at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, was quietly conducting his own rocket research. Entirely unaware of Tsiolkovsky or Esnault-Pelterie, he submitted patent applications for both a liquid-fueled rocket and a multi-stage vehicle.

Like Tsiolkovsky, Goddard had also experienced social isolation during his formative years. A frail only child, he was kept out of school for extended periods due to ill health. As a result, he didn’t graduate from high school until age twenty-one. During his solitary time at home he read stacks of books from the local library, particularly volumes from the science and technology shelves. He also read H. G. Wells’s science-fiction classic The War of the Worlds, which made a lasting impression. At age seventeen in 1899, while aloft in the branches of a cherry tree on his family’s New England farm, Goddard experienced an epiphany that moved him so deeply that he noted the date on which it occurred. “As I looked towards the fields at the east, I imagined how wonderful it would be to make some device which had even the possibility of ascending to Mars. I was a different boy when I descended the tree from when I ascended for existence at last seemed very purposive.”

© NASA

Clark University professor Robert Goddard, who in 1926 launched the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket from a farm in Auburn, Massachusetts. Throughout most of his career he revealed few details about the progress of his research. However, spies in the United States working at the behest of the Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany attempted to breach Goddard’s wall of secrecy.

During World War I, while teaching at Clark University, Goddard obtained research funding from the War Department for an experimental tube-launched solid-fuel rocket rifle, an early version of what would become the bazooka. He also proposed a rocket that could ascend seventy miles into the atmosphere and carry high explosives or poison gas at least two hundred miles. But after the Armistice, no American military officials thought long-range missiles a subject worthy of further research, so Goddard sought to find support elsewhere.

It was a technical paper funded and published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1920 that suddenly placed Goddard’s name on newspaper front pages around the world. “A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes” proposed that a rocket could be used for the scientific exploration of the atmosphere, placing artificial satellites into orbit, aiding weather forecasting, and physically hitting the Moon. His paper made no mention of human space travel to the Moon; however, many newspaper reports heralded his study with dramatic headlines implying Goddard was working on a moon rocket that would transport human passengers.

Within weeks, The New York Times announced that a twenty-four-year-old pilot of the New York City Air Police had willingly volunteered to be the first person to fly to Mars. Concerned that the United States must maintain its position with other nations in the air, Captain Claude Collins said he would ride the world’s first interplanetary rocket, provided a ten-thousand-dollar life-insurance policy was part of the arrangement. The Times treated Goddard somewhat less admiringly than it did Captain Collins when it published a scathing editorial taking the college professor to task for believing that a rocket would function in the vacuum of space. The Times slammed Goddard, claiming he was unfamiliar with basic Newtonian physics and showed a “lack of knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.” His pride wounded, Goddard soon grew wary of the popular press. Sensational stories about the American professor’s forthcoming moon-rocket flight continued to appear in publications around the globe throughout the early 1920s. And occasionally Goddard was complicit, supplying dramatic quotations apparently intended to entice potential investors, such as his plan for a giant passenger rocket capable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a few minutes.

However, when Goddard actually made history with the world’s first successful launch of a liquid-fueled rocket on March 16, 1926, in Auburn, Massachusetts, no journalists were present, and no account appeared in contemporary newspapers. The date is now celebrated as the dawn of the space age, but for most of his career Goddard carefully guarded information about his research, afraid that others might steal his secrets and profit from his work.

THE SENSATIONAL ATTENTION accorded Goddard’s Smithsonian paper appeared in the European press just as the third of the trio of rocketry pioneers, a former medical student from Austro-Hungaria named Hermann Oberth, was readying his work for academic review. Born in 1894, Oberth was a brilliant student of mathematics and had been fascinated by the idea of spaceflight since age twelve, when he committed to memory passages from Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon. Oberth had tried to interest military strategists in a proposal for long-range missiles during the First World War, but his paper went unread. After the war he revised his work, this time focusing on the basic mathematics underlying space travel. However, when he submitted the paper as his doctoral dissertation, it was rejected as “too fantastic.”

© Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM 87-5770)

Hermann Oberth photographed in his workshop while assisting on the production of the German science-fiction feature film Woman in the Moon. When he was ten years old, the telephone and the automobile first appeared in his rural hometown. In his later years he witnessed the launches of Apollo 11 and the space shuttle Challenger.

Undeterred, Oberth obstinately continued to pursue his studies independently, dismissing his instructors as unworthy to judge his work. For this gifted mathematician, formulating the necessary calculations for space travel was a diverting intellectual exercise that gave him a sense of ownership and agency. “This was nothing but a hobby for me,” he said, “like catching butterflies or collecting stamps for other people, with the only difference that I was engaged in rocket development.”

He asked himself a series of questions that would need to be answered if humans were to enter outer space: Which propellant should be used—liquid or solid? Is interplanetary travel possible? Can humans adapt to weightlessness? How might humans nourish themselves in space? Can humans wearing space suits venture outside vehicles? In contrast to Goddard’s more cautious approach, Oberth embraced the unknown by posing imaginative questions prompted by his reading of science fiction. He then devised practical solutions founded on his mathematical and engineering expertise.

In 1923 he published a short technical version of his dissertation, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space), personally paying the expense of the book’s entire printing. Fortunately, his vanity-publishing project was a wise decision. By issuing the book in German, which in the early twentieth century was the dominant language of the scientific community, Oberth established himself as the world’s leading theorist of human spaceflight, overshadowing the more reclusive Goddard. When he read the German monograph, Goddard believed Oberth had borrowed his ideas without proper attribution, though there is little evidence to support his suspicions.

The Rocket into Interplanetary Space appeared at a moment when many Germans were hungry for something bold, dynamic, and modern to restore the nation’s pride, following the defeat in World War I. The 1920s were a time of experimentation in art, film, and architecture and the arrival of new consumer technologies like radio, air travel, and neon lighting. The speed, power, and streamlined design of rockets became associated with a future of exciting possibilites. Less than four years after the publication of Oberth’s book, the Verein für Raumschiffahrt—or Society for Space Travel—was formed in Germany, and it soon became the world’s leading rocketry organization. It published a journal, held conferences, and conducted research experiments. But the stunts of Max Valier, one of the society’s founders, were what drew the greatest media attention: He strapped himself into a rocket-powered car and hurtled down a racetrack, trailing a cloud of smoke and flame. Such daredevil exploits proved to be an effective way of generating publicity but did little to boost the society’s scientific reputation.

Not long after the society’s founding, the noted Austrian-German filmmaker Fritz Lang approached it for technical assistance in connection with his forthcoming science-fiction space epic, Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon), a follow-up to his international hit Metropolis. Lang hired Oberth, the society’s figurehead president, to be the film’s technical adviser. The film’s studio also engaged Oberth to build a functioning liquid-fuel rocket to promote the movie’s premiere, a project that, despite providing the society needed research-and-development money, was unsuccessful.

Albert Einstein and other scientists were among the celebrities who attended the film’s opening, but the only rocket to be seen that night was the one that appeared on the screen, created by the studio’s special-effects department. Although Frau im Mond wasn’t a critical hit, it was historically important for introducing the world’s first rocket countdown. Fritz Lang created it as a dramatic device to instill suspense in the final moments before the blastoff. It was such an effective way to focus attention and convey the sequence of procedures prior to liftoff that rocket engineers around the world immediately adopted it.

Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, reports of Goddard’s moon rocket and Oberth’s scientific monograph prompted Russian space enthusiasts to stake their country’s claim by recognizing that Konstantin Tsiolkovsky had been the first to mathematically publish the rocket equation. Tsiolkovsky was in his mid-sixties when he received his vindication, and it coincided with a brief and bizarre moment of space-travel mania. After the First World War, revolution, and a civil war, Russia was in the throes of change, as audacious and provocative new ideas permeated the culture; among them was a renewed interest in utopian Russian cosmism, and a desire to explore new worlds. One of Tsiolkovsky’s leading Soviet advocates rallied followers with the slogan “Forward to Mars!”